13TH SHANGHAI BIENNALE CURATORS

On Fluidity, Collaboration, and Remains: A Conversation, Part 1

- 23.01.2021

- ConversationExhibition/Program DesignShanghaiAndrés JaqueYou MiFilipa RamosLucia PietroiustiMarina OteroInfrastructureResearch (Artistic/Curatorial)CuratingClimate/EnvironmentSolidarityCollaborationCosmopolitanismSustainabilityDiscursivityPaula VilaplanaTong WenminItziar OkarizAstrida NeimanisClare BrittonHimali Singh SoinDavid Soin TappeserJenna SutelaBasak SenovaSylvie Fortin

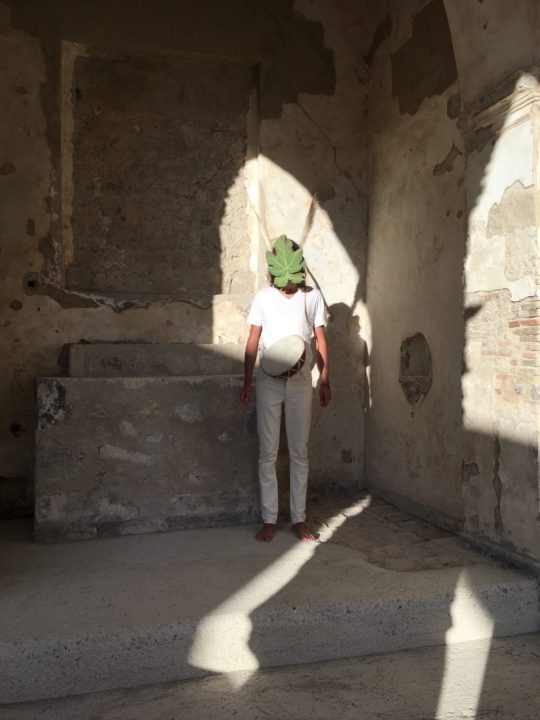

Image: Paula Vilaplana. Produced for the 13th Shanghai Biennale.

SYLVIE FORTIN The Shanghai Biennale is the oldest biennial in China, which gives it global significance. The Biennale also plays a critical role in China and in the wider region. This probably comes with specific institutional and civic expectations. Can we talk about the institutional expectations for the 13th Shanghai Biennale, which is currently underway? What expectations were either directly or indirectly formulated when you began the project? What has come to the fore as you develop the 13th Shanghai Biennale now?

ANDRÉS JAQUE This biennial in Shanghai plays a very particular role in Chinese politics at this time in history. A huge transition is currently underway there; internal tensions translate into very particular social compositions and the coexistence of many societies. The invitation to participate extended to us, who are mostly transnational agents, is a request for diplomacy, an invitation to think about the ways in which certain layers of Chinese society could be gaining voice internally while also aligning themselves globally or internationally. This is one level.

The second level has to do with other jurisdictions—the politics and aesthetics as well as the discourse and associations that exceed the capacity of nation-states to regulate or control. These have to do with ecology, the environmental crisis, the constitution of bodies and socialities. While these questions are very important in contemporary politics, they have not yet gained currency in the discourse in Shanghai and other parts of China.

These two considerations led to our being selected; this, I feel, is the institutional call. But we cannot be naive; this call is issued within the larger framework of institutional demands, which are not all necessarily aligned. That’s where diplomacy is needed if we are to gain a voice within the broader ecosystem and to provide a space for others to gain that voice.

Image: Paula Vilaplana. Produced for the 13th Shanghai Biennale.

Image: Paula Vilaplana. Produced for the 13th Shanghai Biennale.

FILIPA RAMOS Sometimes there’s a difference between what institutions think they want and what they actually want. The discrepancy between their selection criteria and their actual choices often reveals it, in the sense that they also want to be challenged, to be pushed beyond what they usually deliver. It’s 2020 and we’re going through so much change that institutions need to transform, adapt, and challenge themselves to invent new formats, approaches, and practices. We’re trying to attune ourselves to one another, hopefully with enthusiasm and joy, as we discover how our shared desires, needs, and expectations meet in unexpected ways.

YOU MI At this moment, China is dealing with ecological disaster and social tensions. This causes anxiety on all fronts. As we speak, many parts of China are experiencing one of the worst floods in history. We can address these regional realities quite freely. In a way, we’re expected to address these issues. This requires diplomacy and constructive dialogue, which to some extent is still possible in China, despite the common conception of the opposite from outside the country.

More broadly, people in China generally still have a future-oriented perspective; such belief in the future is not so prevalent in Europe, where people tend to be fixated on a glorious history. In China, a naïve, almost blind, opportunistic and optimistic attitude towards the future is dominant. It was palpable when we were speaking with the biennial director, for example. She’s the one who urged us to look into other possible platforms, including social media and unlikely partnerships for the biennial. A new energy and a new institutional practice are emerging.

Tong Wenmin, A Long Time Ago-PSA, 2020. Performance. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

Tong Wenmin, A Long Time Ago-PSA, 2020. Performance. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

BASAK SENOVA As curators of the Shanghai Biennale, you often talk about collaborative conversations and actions. I am curious about how you came up with the idea of bodies of water and how the five of you work together. Could you talk about your collaborative curatorial methodology?

ANDRÉS JAQUE It’s very organic. Each of us would probably narrate the way in which we eventually defined a methodology quite differently. But certain things are very important. From a practical point of view, we’re not dividing the biennial: no one is in charge of a section or venue. We are organised as a chamber of discussion, from the development of the theme through to the selection of proposals and their presentation. Everything is discussed collectively. Adding to her contribution as curator, Filipa plays a unique role: she is in charge of research and publications. This translates into weekly meetings to which we bring all our proposals, and discuss formats and collaborations. It’s hard to convey but it’s massively enriching: we end up doing things that none of us could do individually.

MARINA OTERO I agree with Andrés. We don’t have a particular methodology but we share trust, respect, and curiosity for what the others can bring. Rather than being very explicit about the different responsibilities, we rely on each other and make it fluid. Each of us has a different background, different experience and expertise, and different ways of working and points of view. We respect and trust what each will bring. This makes certain types of commission possible because it’s not a bureaucratic structure. It is a more organic selection, and we all discover different artists or projects. That’s the joy.

Tong Wenmin, A Long Time Ago-PSA, 2020. Performance. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

Tong Wenmin, A Long Time Ago-PSA, 2020. Performance. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

LUCIA PIETROIUSTI I probably wouldn’t describe any of us as curators, even though we all have exhibition-making experience. One of the things we bring to the methodology is infrastructural analysis: we think about infrastructure as the core around which we build the work. From a pragmatic standpoint, infrastructural thinking extends from analysis and concept to the practical reality of working in institutions. Having all worked with institutions, we are quite aware of the violence they perpetrate on bodies. Thus, our group articulated from the start practices of care and sharing space—giving and receiving space. Combined with distance (we are on three continents) and our other commitments, our process necessarily slows things down. So, the pandemic gave us a sort of extension. We’re slowing down the programme in a way that actually suits our methodology.

SYLVIE FORTIN I’d like to discuss the connection between two concepts we’ve just discussed—time and diplomacy—and the format of the Biennale. You’ve extended the Biennale’s public interface into a year-long endeavour and structured it as a sequence of three phases with different temporalities and proximities: a year-long, sequential, distributed, and generative Biennale. In addition, this sequence seems to follow two movements: gathering and dispersal. How does this format support slowed time and diplomacy?

Tong Wenmin, A Long Time Ago-PSA, 2020. Performance. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

Tong Wenmin, A Long Time Ago-PSA, 2020. Performance. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

ANDRÉS JAQUE We didn’t want to postpone the biennial. Art is not an accessory that is only welcome when everything is going well. Art and artists are fundamental to societies; they are needed precisely when things are challenging. Art responds to the needs of urgent evolutions; it shapes activism. This is why we insisted that the Biennale should not be postponed to a more comfortable time. We wanted to be active, responsibly and with great care for everyone involved, while acknowledging the differences brought about by the pandemic.

While the format needed to change, this didn’t mean that we had to cancel or defer the Biennale. This translates into the times and proximities you were mentioning, Sylvie. Two things guided our discussions: the need to carefully construct our affections, connections, and discussions, and the recasting of expectations beyond the typical visible outcomes for visitors to come and see. This gave us an opportunity to rethink the constitution and role of audiences in biennials; to cast contributors and participants as agents in the entire making of a biennial.

We also imagined that our new format might allow us to rethink the form of the Biennale on the calendar—to renew a sort of contract with contributors, audiences, the city, and many other actors. By changing the format without changing the schedule, we took care not to inconvenience anyone. While retaining the planned opening date, we could convince people to do something different, to think of the Biennale as a way to build up a relationship, to embody together the ways it was possible, and then think of the presentation of artworks—at the end rather than at the beginning of the Biennale—as something that could come out of the discussion.

Essentially, we reversed the Biennale so that it would initiate an incremental process by nurturing mutual care and demands, which would materialise, crystallise, or solidify—rather than conclude—into something more concretely visible. Meanwhile, we could grow the affections, discussions, and collaborations, not as a closed conversation between curators, artists, and contributors, but as a process open to participation. Our idea was to share this experience throughout the Biennale, which is why we decided to start our three-phase programme with A Wet-Run Rehearsal, a moment when we would present what we were doing very openly, and then invite others to join and grow with us throughout the process of the Ecosystem of Alliances, towards the exhibition.

Itziar Okariz and her daughter, Ocean Breath, 2020. Online performance. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

Itziar Okariz and her daughter, Ocean Breath, 2020. Online performance. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

MARINA OTERO We don’t necessarily see the exhibition as a final display of artefacts awaiting visitors. What is an exhibition? How do you engage with it? How many faces does it have? As Andrés said, it’s not work that happens backstage and away from view, followed by an opening and a period of display. Rather, an exhibition includes moments of research, process, and display integrated across time and space. That’s our experiment.

BASAK SENOVA It’s a thought-provoking approach to exhibition making. Knowing that three of you are architects, can you speak about your relationship to the Power Station as a venue? What’s your perspective on it? How do this specific venue and the spatial design of the exhibition, as well as the related research and data, come together?

Power Station of Art, Shanghai.

Power Station of Art, Shanghai.

ANDRÉS JAQUE This is crucial. For us, buildings are not only venues, stages, or receptacles, but real participants and contributors. There’s no division between the Biennale’s theme and its actual materiality or physicality. We are equal to the building in the sense that our bodies are participating in the realities that the biennial is exploring; that’s a fundamental dimension of our proposal.

Certain solidarities connect us with the city of Shanghai, the Huangpu River, and the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, from which melting glaciers bring sediments. We’re all individually part of this: my body is physically constituted by and connected to this reality. I remember Lucia and me going to see the pipes that connect the Power Station of Art to the river, whose water circulates in the building and cools it—the river flows through the building, it is one of its bodies. This form of solidarity is not rhetorical: it’s present. Architecture is not fundamentally different from other bodies.

This is crucial methodologically and thematically as we try to relate to venues differently. We’re trying to activate the material and physical participation of the buildings, infrastructures, and public spaces where the biennale takes place. The presentation of a work in a particular location is more than a matter of placement. We’re carefully working to situate the work within a fluid assemblage of thematic and material connections, in which the exchange between works, buildings, and bodies is both intellectual and physical, if not metabolic. Not only is this fundamentally different from mere display, but it also allows the exhibition sites to become a crucial source of criticality. There are forms of material solidarity and conflict that only emerge when art practices, bodies, infrastructures, and environmental entities come together. These tensions were already operating in the city. Our work consists in enabling these discussions and providing them space and time to develop.

SYLVIE FORTIN How does this connected space from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, through Shanghai and to the ocean, relate to your previous biennial projects, such as Andrés with Manifesta in Palermo and Marina with Manifesta in Marseille? Bodies of Water, as you’ve just described it, connects to vaster aqueous networks, on both the planetary and imaginary scales with which you all, individually and collectively, engage. To put it another way, instead of thinking of the Power Station of Art as a host/container or the 13th Shanghai Biennale as the exhibition—that is, instead of adopting a project-based curatorial approach—you mobilise the infrastructural analysis of architectural thinking to recast or align each curatorial project/opportunity into a practice. Might we say that your curatorial practice is a lifelong practice or inquiry?

MARINA OTERO While I do curatorial work, I don’t describe myself as a curator. I think that I operate as an architect in my understanding of space and the relations between different scales, spaces, bodies, and resources through forms. I bring together different themes, objects, artefacts, and materials to make them resonate and to foreground certain narratives. I like your idea of curatorial work as a lifelong pursuit.

I feel very connected to this notion and to the people with whom I’m working on this project. Many of my independent projects have been informed by what I learned from them. In Palermo, for example, Andrés brought architecture and art together in a very sophisticated yet humble way. It’s true that the Shanghai Biennale is informed by all these experiences. The beauty of this group is that, instead of coming together to discover what we have in common and reduce it to a clean and simple big idea, we welcome dissonance; or rather, we bring very specific obsessions. In her book Bodies of Water, Astrida Neimanis says that bodies of water allow both commonality and differences. The 13th Shanghai Biennale is a little bit of Marseille, Palermo, London, Helsinki, and many other places; it’s a unique project, watered by many places and practices. Its processes are fluid; it uses, reuses, and reorganises many things. In addition to these commonalities, it is also informed by the specificities of Shanghai today.

Astrida Neimanis and Clare Britton, The river ends as the ocean, 2020. Online performance lecture. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

Astrida Neimanis and Clare Britton, The river ends as the ocean, 2020. Online performance lecture. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

YOU MI We’re connected by something more profound than a theme or topic. We also share the ability to jump scale, which means being able to engage with each scale in a specialised way and to articulate different politics at different scales, from the scale of molecules and other small species, to what humans can somehow physically register, to planetary infrastructure. Such fluidity of scale requires different skills in order to engage with questions ranging from the material—how materials come together on cellular and planetary scales—to the social dimension of infrastructure. We are all interested in these questions of scale and their different sociologies.

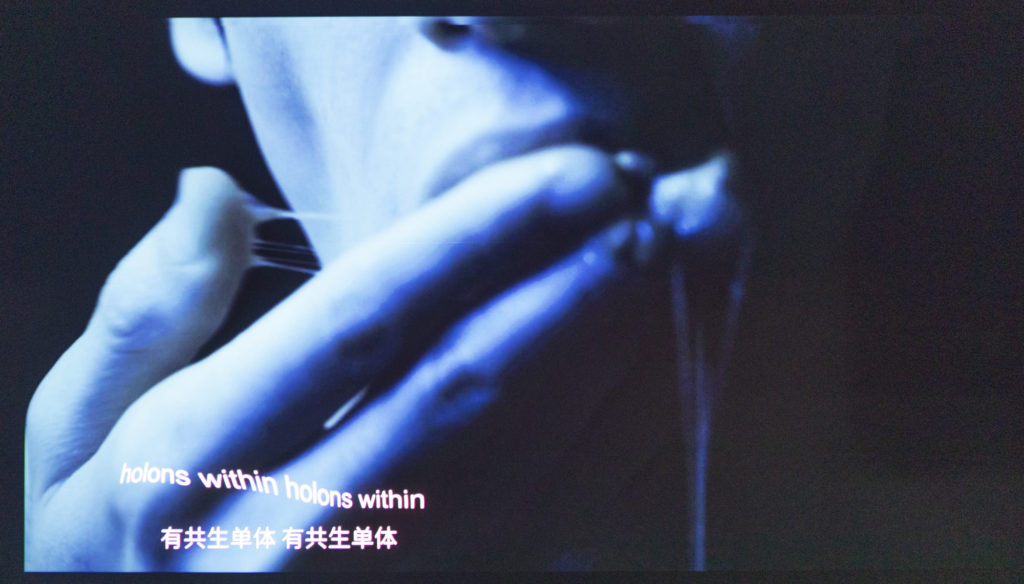

Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser, In the Spirit of the Fountain: a Performance at Pompeii, 2020. Online performance. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser, In the Spirit of the Fountain: a Performance at Pompeii, 2020. Online performance. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

SYLVIE FORTIN We talked earlier about your sequential and distributed format, with moments of gathering and dispersal, about scale shifting, and about your title, Bodies of Water. Each of these dimensions mobilises narrative histories and potentials in several ways. That’s very political. I’m wondering about the role of narrative as a strategy to open a shared space for discussion. Could you talk about narratives in your own work and in curating as you define that practice?

LUCIA PIETROIUSTI Our title invokes the relationship between narrative and the stuff of the world. It is a metaphor, but it also refers to actual water, its flows and politics, the regulatory bodies that determine how water bodies operate, are extracted, relate to each other, have agency, and so on. This is true at all scales. In Western traditions, the mythological and the ontological domains have been separated. However, if one retraces their genealogies, one finds that narrative, myth, religion, spirituality, and art were not excess or leisure-time activities distinct from agricultural evolution; they were a part of it. They contained the memory of how things came to be; they contained knowledge. Metaphor is actually the most resilient technology; it alone traverses millennia. When we operate at the level of narrative, we tap into an important root system, the stuff of law, agriculture, technology and so on.

Some environmental movements, particularly the ones that are invested in the intersectionality of environmental, social justice, and Indigenous rights, are becoming more aware that system change requires mythology change. We need to shift our cultural myths. This is possible, as we know.

We also share a post-anthropocentric attitude, which is deeply connected with memory. All of these things have something to do with the question of narrative.

FILIPA RAMOS I would add something about the practical conception of the exhibition. We want artworks to be evocative and capacious enough to welcome multiple readings and interpretations, not to simply stand for or illustrate our ideas. We see the exhibition as a prompt or a proposition to generate narratives and knowledge in dialogue with the topics that interest us.

Instead of publishing a conventional catalogue, we are inviting artists, art historians, geographers, science-fiction writers, and others to engage with the ideas of the exhibition. This book doesn’t explain the exhibition but expands it: it’s an experiment to understand how a show can generate concepts, affects, and intersections of various epistemological traditions.

Your question concerns both the present and the future of the exhibition, once it is no longer on view. What will remain? Hopefully the embodied narratives, carried by the visitors, which are personal, subjective, and multiple. How can the Shanghai Biennale also leave traces of parallel narratives that have a life of their own, apart from the exhibition? The book has its own life, which will hopefully remain relevant over time.

Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser, In the Spirit of the Fountain: a Performance at Pompeii, 2020. Online performance. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser, In the Spirit of the Fountain: a Performance at Pompeii, 2020. Online performance. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

SYLVIE FORTIN It’s a relay, or, to follow your water metaphor, it’s a message in a bottle thrown into the sea. In addition to the experience of the exhibition and the generative experiment of the book, I wonder about a third form of encounter, the rumour. It’s a traditional form: the rumour spreading from one person to others, at times like wildfire or a virus. Today, social media are rumour vehicles. Many people will experience the biennial through rumour, which also mobilises narrative.

MARINA OTERO Yes, this is very important. We’ve had several conversations about the different forms of engagement with our research themes. We are all very involved in research or academic writing. We are also keen to develop certain narratives around these themes explicitly. The field of art tends to approach thematics more open-endedly, letting the art works talk. We are doing a combination: our curatorial voice might be louder in some parts of the exhibition, whereas in others the voices of our contributors are more present. And as you were saying, rumours will be another constituent. We’re trying to find a balance in terms of who’s talking on behalf of whom. This is exciting. When should you step back or to the side and let others talk? When should you advance your concerns and challenges? I’ve never experienced such a rich engagement with these questions. I’m learning a lot from the experiences of others.

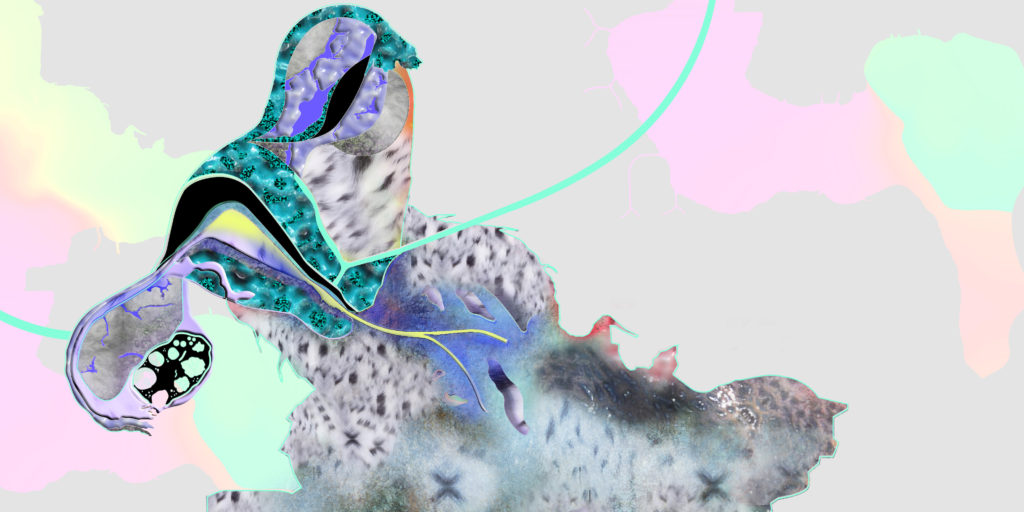

Jenna Sutela, Holobiont, 2018. Installation view of the Flowing Images section of the 13th Shanghai Biennale, 2020, at the Power Station of Art, Shanghai. Courtesy of Power Station of Art.

BASAK SENOVA In addition to the aspect of memory, which Lucia mentioned, and the geopolitical and social urgencies, there is also the issue of sustainability. The notion of fluidity brings them all together almost in a poetic way. Could you also talk about this notion in terms of sustainability?

LUCIA PIETROIUSTI Is fluidity good or bad? This question took up many of our conversations. While we welcome more fluid human or national boundaries, how do we account for things like turbo-capitalist liquidity? It’s important for us to find ourselves in that back and forth. In the Biennale, fluidity is posited neither as toxicity nor as solution; fluidity is the internal logic of the way we relate—or stack—ecology, infrastructure, technology, and politics.

ANDRÉS JAQUE This question, which also relates to narrative, has been the centre of ongoing discussions. The political traditions of ecological action are usually separated from those of gender struggle and queerness. The political dimension of narrative is a question of composition, and thus not that different from that of the built world. In order to respond to these questions, we need to bring together discussions of ecology, bodies, and violence. This has been a central concern for us.

It also has to do with sustainability, if we carefully consider the ways in which flows have been stabilised and their control accelerated as a means of modern development and progress. We need to understand that ecology now means more than correcting resource exploitation; ecology actually questions the way we depict humans’ relations to humans and to others. Thus, it’s much more than a corrective; it’s a process of reconstruction. We need to reconcile traditions that have mobilised the body as a site for politics with those of environmental politics.

These traditions call for an understanding that the corporate rhetoric of sustainability and sustainable development is intrinsically connected to the modern culture of exploitation—where the abusive overexploitation of nature by humans is directly connected to the exploitation of humans by fellow humans through colonial and neoliberal practices and technologies. This biennial gathers cooperating bodies and environments as it imagines and advocates for a reconsideration of interspecies alliances. These require aesthetic and political articulation.

This is particularly important in China, where sustainability and ecology are seen as extensions of modern development. Here, the Biennale can intervene in an ongoing narrative by introducing doubt and providing space for alternatives.

LUCIA PIETROIUSTI The words “sustainability” and “resilience” are found in the mission statements of most organisations today. They usually mean the institution’s own sustainability and resilience. While one doesn’t want to get bogged down in language—since as Andrés just said, the environmental question does not emerge at the level of language, in terms of narratives—the words we use do matter. Today, environmental efforts are various and intersectional; they offer many, at times contradictory, versions of a solution. One of our greatest challenges is coming to terms with infinite complexities, to echo Joanna Macy. If we don’t, strategic political drives will simply clash with each other, draining enormous amounts of active hope.

Astrida Neimanis and Clare Britton, The river ends as the ocean, 2020. Online performance lecture. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

Astrida Neimanis and Clare Britton, The river ends as the ocean, 2020. Online performance lecture. Phase 1: *A* Wet-Run Rehearsal, 13th Shanghai Biennale. Courtesy of the artists and Power Station of Art.

SYLVIE FORTIN I’m invested in expanding the concept of cosmopolitanism by redefining the “cosmos” part of the term. Reclaiming the capaciousness of the term “cosmos” allows us to make that jump from a human-centred to more-than-human forms of “internationalism.” I wonder if that’s something that is part of your conversations.

LUCIA PIETROIUSTI Anthropocentrism centres on a particular kind of human. Post-anthropocentric thought acknowledges that the Anthropos is the traditional privilege of a very specific group of persons. New ecological thinking merges and emerges from a broad field of radical anthropology, feminist science and technology studies, anti-racism and decolonial thinking, and disability studies. Looking at the Anthropos’s relationship to movement, for example, reveals that movement is predicated on a mobility that is the prerogative of a certain number of individuals. When you’re thinking about plants and humans together in the same field, normative categories burst open.

ANDRÉS JAQUE This is all connected to the Yangtze River and the Power Station of Art. The Power Station of Art is the power station that fuelled the industrialisation of the Huangpu River, which allowed the city to reposition itself in the era of early globalisation. This process of industrialization imposed a way for humans to deal with nature. Some humans sought to impose a particular notion of nature on all humans, a particular way of controlling time, their bodies, and their metabolisms. This is often lost in environmental activism. Now is the moment to underscore this point, to see its impact on contemporary artistic practices, and to understand how it aligns with broader political action.

FILIPA RAMOS It’s interesting to think of cosmopolitanism beyond the human. You Mi spoke about the relationship between the floods in southern China and “Bodies of Water,” the concept of the biennial, to which this notion of a post-human cosmopolitanism may well relate: flows and fluids traversing, permeating, and reshaping environments and relationships. Likewise, how can our methodology and interests converge and assemble bodies and peoples as well as structures and fluxes and foster their togetherness instead of limiting itself to discourse, either about ecology or internationalism? Throughout the entire project, we’re trying to imagine new forms of togetherness by mobilizing liquidity: to assert the embodied togetherness of human and non-human bodies, fluxes and flows.

The liquid reference is metaphorical but also real; this liquidity is concrete, a way of thinking with flow, fluids, and liquids but also through the correlations between effects, bodies, and ways of being in the world.

NOTES

This conversation between Andrés Jaque, Filipa Ramos, You Mi, Marina Otero, and Lucia Pietroiusti and PASS’s Sylvie Fortin and Basak Senova took place on July 22, 2020.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Andrés Jaque is an architect, writer, and curator internationally renowned as one of the initiators of interscalar and transmedium approaches to urban and territorial studies. His work explores environments as the entanglement of life, bodies, and technologies. He is the founder of the Office for Political Innovation, a New York and Madrid-based agency working at the intersection of research, critical environmental practices, and design.

Jaque is the Director of Columbia University, Advanced Architectural Design Program. His publications include Superpowers of Scale (2019), Transmaterial Politics (2017), Transmaterial/Calculable (2017), PHANTOM. Mies as Rendered Society (2013), Different Kinds of Water Pouring into a Swimming Pool (2013), Everyday Politics (2011) and Melnikov. Car-park for 1000 vehicles (2004). In 2018 he co-curated Manifesta 12, The Planetary Garden. Cultivating Coexistence, in Palermo.

Marina Otero Verzier is an architect based in Rotterdam. She is Head of the Social Design Masters at the Design Academy Eindhoven. She was the curator of I See That I See What You Don’t See at La Triennale Di Milano (2019), Work, Body, Leisure, the Dutch Pavilion at the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale (2018), and Chief Curator of the 2016 Oslo Architecture Triennale (with the After Belonging Agency). Otero is a co-editor of Unmanned: Architecture and Security Series (2016), After Belonging: The Objects, Spaces, and Territories of the Ways We Stay In Transit (2016), Architecture of Appropriation (2019), and More-than-Human (2020), and the editor of Work, Body, Leisure (2018).

Lucia Pietroiusti is the curator of Sun & Sea (Marina) by Rugile Barzdziukaite, Vaiva Grainyte and Lina Lapelyte, the Lithuanian Pavilion at the 58th Biennale di Venezia, as well as Curator of General Ecology at the Serpentine Galleries, London. General Ecology is a strategic, cross-organisational effort dedicated to the implementation of ecological principles throughout all of the Galleries’ exhibitions, programmes and networks. In 2021, Pietroiusti will join James Bridle in curating a section of Helsinki Festival, dedicated to artificial and more-than-human intelligences.

Dr. You Mi is a Beijing-born curator, researcher, and lecturer at the Academy of Media Arts Cologne and Aalto University, Helsinki. Her writings have appeared in Performance Research, MaHKUscript: Journal of Fine Art Research, Southeast of Now, and Yishu, among others. In 2011, she co-initiated and was a committee member of the project “Transnational Dialogues,” an exchange platform between artists and thinkers from China, Europe and Brazil. She is a fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Germany, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, and Independent Curators International, New York. She also serves as a member of the Academy of Arts of the World, Cologne a director of Arthub, Shanghai as well as an advisor to the Institute for Provocation, Beijing.

Lisbon-born Filipa Ramos is a writer and lecturer based in London. She is Curator of Art Basel Film and a founding curator of Vdrome, which she runs with Andrea Lissoni. Most recently, she curated Animalesque, a group exhibition on becoming other, at the Bildmuseet Umeå, Sweden (Summer 2019) and BALTIC, Gateshead, UK (Winter 2019/20).

Ramos was Associate Editor of Manifesta Journal and a contributor to Documenta 13 (2012) and Documenta 14 (2017). Her writing and research on art, film, and nature has been published in magazines and catalogues worldwide. She authored Lost and Found (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2009) and edited Animals (London: Whitechapel Gallery/MIT Press, 2016).