NATASHA GINWALA

Double Nature

- 17.12.2018

- EssayCuratingMechelenNatasha GinwalaLawrence Abu HamdanChihiro MinatoSamson YoungWadada Leo SmithGyörgy LigetiToshi IchiyanagiKen JacobsEricka BeckmanLis RhodesFrank and Lillian GilbrethTarek AtouiOtobong NkangaRitu SarinKarrabing Film CollectiveCouncilTenzing SonamAgencyFreethoughtJean PainlevéPauline Oliveros

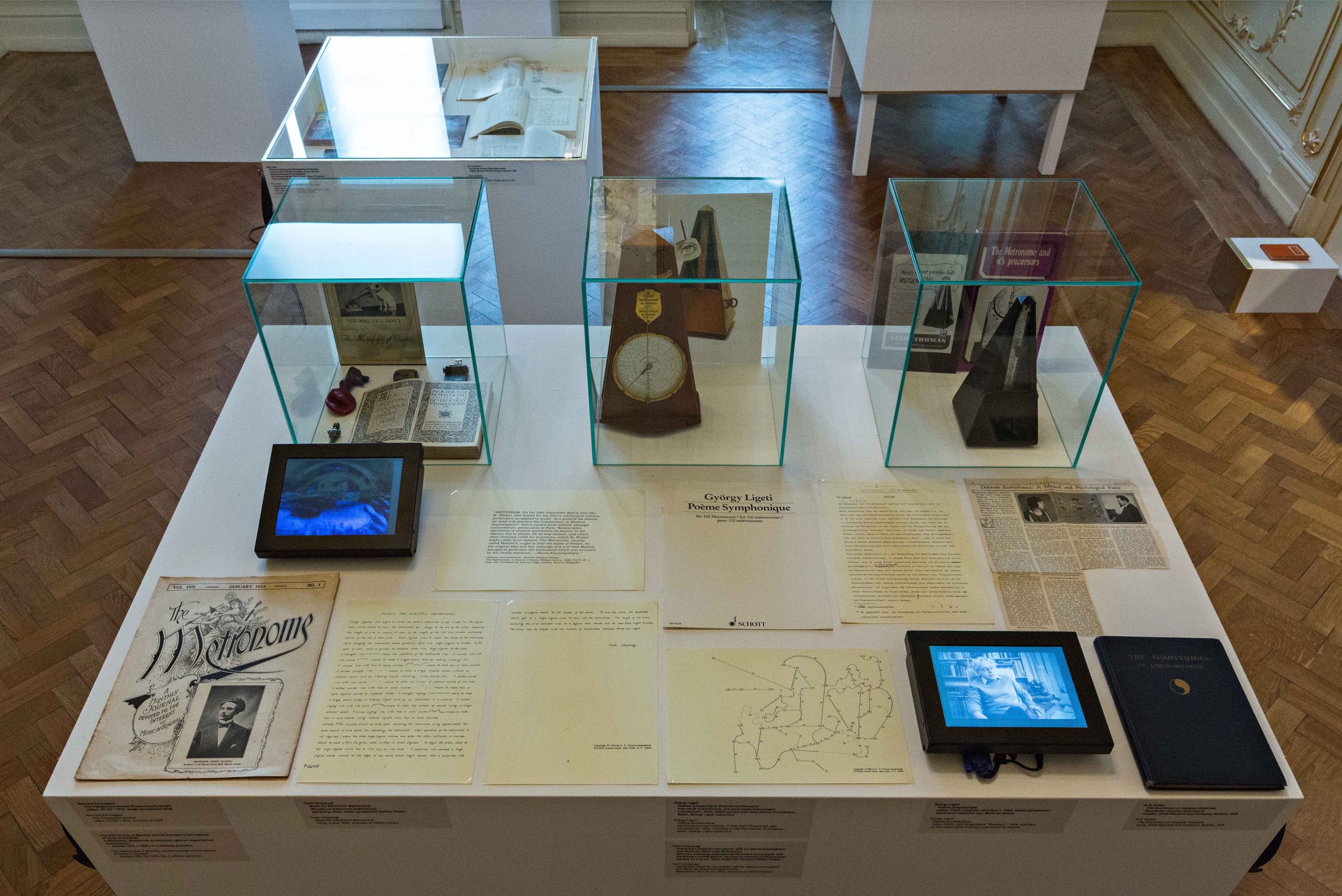

Exhibition view of Contour Biennale 8, Polyphonic Worlds: Justice as Medium, Mechelen, 2017. Photo: Kristof Vrancken. Courtesy of the artists and Contour Biennale 8.

What if, as I’m suggesting, precarity is the condition of our time – or, to put it another way, what if our time is ripe for sensing precarity? What if precarity, indeterminacy, and what we imagine as trivial are the center of the systematicity we seek?

Precarity is the condition of being vulnerable to others. Unpredictable encounters transform us; we are not in control, even of ourselves. Unable to rely on a stable structure of community, we are thrown into shifting assemblages, which remake us as well as our others.

Exhibition view of Contour Biennale 8, Polyphonic Worlds: Justice as Medium, Mechelen, 2017. Photo: Kristof Vrancken. Courtesy of the artists and Contour Biennale 8.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Two You, 2012, vinyl prints. Dimensions variable. Exhibition view of The Museum of Rhythm, Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź, 2016. Photo: Piotr Tomczyk. Courtesy of the artist.

I seek to address biennial production in planetary terms – as a polyphonic cultural and politico-economic landscape that is extractive as well as fecund. In this rhizomatic field, artistic and social forces of hostility and hospitality are in agonistic play. There is no denying that biennial making is moving in increasingly diverse directions, eschewing both epic narratives and formal homogeny in its local and international cultural assemblages.

It appears there are conscious attempts at altering biennial structures to reflect an aesthetic of fragmentation – active dispersal of the physical exhibition site into episodic and multi-situated curatorial propositions, while also branching into online knowledge platforms. And crucially, there is a desire to support multifaceted projects and artistic practices that call on durational labour, requiring collaboration across several exhibitory encounters. This text is a personal articulation of the critical plenitude of the biennial form.

Modern Monsters/Death and Life of Fiction, the 2012 edition of the Taipei Biennial, featured a number of speculative mini- museums that took up history-telling exercises by moving between documentary evidence and fictionalisation.2 Curated by Anselm Franke and held at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, this biennial became a host to various imaginative museums interweaving artistic works, scientific documents, legal records and fictional accounts. Together, these museums purposefully disaggregated official chronicles of modernisation in East Asia and introduced perspectives that trace marginal accounts from the longue durée of colonial modernity, systemic violence and memorialisation. The biennial performed as a meta-text filled with absurd, slippery and disjointed annotated narratives, building on the blind spots of modernist historiography and its mind-numbing imprints that have structurally defined Western consciousness.

Photographer and theorist Chihiro Minato’s project The Museum of Gourd was envisioned as a sensory museum embodying the principles of fluidity and freedom.3 One year after the Tohoku earthquake and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, Minato drew upon the legend of the catfish monster Namazu who, having caused tectonic ruptures in the islands of Japan, was captured and contained with a gourd by the deity Kashima.4 In casting the gourd as protagonist, the artist provided an affective montage that addresses the trembling earth caught in a toxic knot, outlining the visceral dangers of nuclear energy while centralising open systems of life. Within the mini-museum’s (temporary) collection, the gourd was also situated as the key source material for musical instruments across various geographies – from Japan to Africa.

It appeared fitting then that my project, The Museum of Rhythm, which adopted Marxist sociologist and philosopher Henri Lefebvre’s technique of rhythmanalysis5 as curatorial strategy to distort the regulated pulse of modernism, was realised in The Museum of Gourd’s vicinity. The Museum of Rhythm is a speculative institution that engages rhythm as a tool for interrogating the foundations of modernity and the sensual complex of time in daily experience. In Henri Lefebvre’s writings on rhythmanalysis, he notes that the rhythmanalyst, as a character charged with this task, will function as a living metronome, using the body as a tuning agent and thereby bringing into consciousness the internal beat with exterior scores of the environment.6

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Two You, 2012, vinyl prints. Dimensions variable. Exhibition view of The Museum of Rhythm, Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź, 2016. Photo: Piotr Tomczyk. Courtesy of the artist.

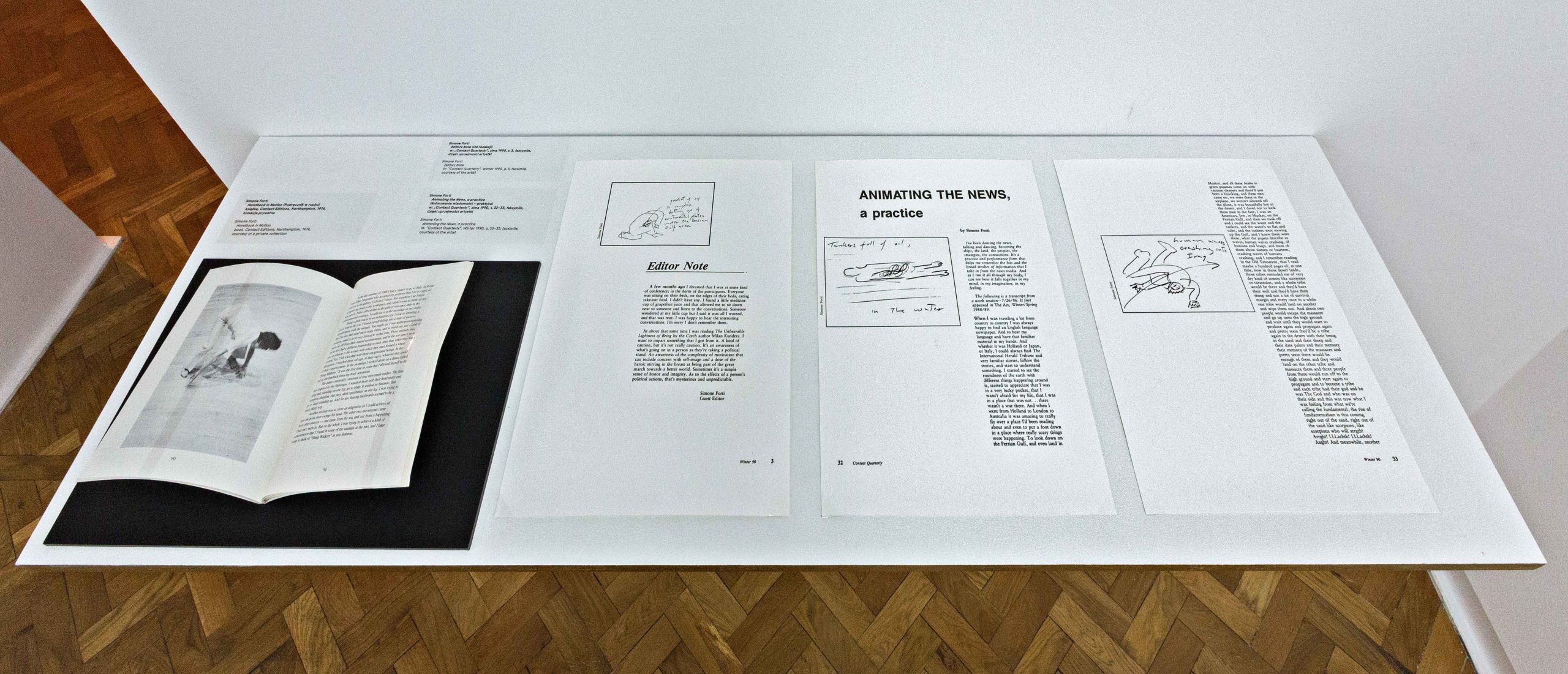

Taking up this biennial’s engagement in the production of new kinds of situated knowledge, The Museum of Rhythm grappled with the borders between the organic and mechanised schemes of rhythm acting upon the human-animal body. Its display included the surrealist science films by Jean Painlevé on the life cycle and dance of molluscs; Simone Forti’s Handbook in Motion, a personal manual on dance improvisation as a way of life; graphic and instructional drawings and scores that challenge traditional forms of musical notation by Toshi Ichiyanagi, György Ligeti, Wadada Leo Smith and Samson Young; and the flickering, hallucination-inducing films and celluloid experiments of Ken Jacobs, Ericka Beckman and Lis Rhodes. Converting the body’s labour into rhythmic units of industrial capital, a selection of time-motion studies and workflow charts by Frank and Lillian Gilbreth were also exhibited.

These descriptive studies, which focused on fatigue reduction to maximised human production, constitute one of the earliest archives on scientific management and labour study. Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s voice-activated Aural Contract Audio Archive presented his ongoing inquiry into the politics of listening, testimonial evidence and courtroom narrations, bringing together acoustic imprints to form a constellation of performed readings and audio documentary.

The Museum of Rhythm has continued as an iterant project beyond the biennial timeframe, operating as a quasi-institution activated across different platforms. So far, it has found contextualised presences in an online journal,7 lecture-performances, a radio interview and an exhibition at Muzeum Sztuki Łódź.8

Biennial making is organised around the conundrum of slow-moving internal research and the accelerated timeline of artistic and logistical production that yields an anachronistic temporality. As a curator one must defy or keep up with the pressures around the public staging of creative processes that are often deeply personal in character. One question has perhaps never fully been answered: How may we, as exhibition organisers, formulate practices that reduce the tensions found in the paradox between a large-scale exhibition’s timescale and the decelerated engagement required for community building and educational initiatives?

The question of learning in recurring exhibitions has begun to be addressed by initiatives such as the 2016 edition of Bergen Assembly, which abandoned the two-year production cycle in favour of projects such as Tarek Atoui’s WITHIN / Infinite Ear, organised as a curatorial collaboration with Council (Sandra Terdjman and Grégory Castéra). Initially developed through the Sharjah Art Foundation and encompassing various iterations, WITHIN / Infinite Ear engaged acoustic and electronic instrument makers, musicians, software engineers and composers in producing music with musicians of different hearing abilities.

In Bergen, the public rehearsals, workshops and concerts formed a flexible sonic architecture within an abandoned swimming pool.9 The biennial experience therefore entailed improvisational processes, haptic musicality and exercises animating the acoustic potency of our daily lives and a vast gradient of silence we rarely consider. WITHIN / Infinite Ear led visitors to encounter the sonic field in acts similar to the ‘deep listening’ initiated by Pauline Oliveros. In the same edition, Freethought’s six-chapter exhibition pursued an investigative and discursive methodology to examine planetary scenarios such as the frequently debated ‘End of Oil’ to situating shipping infrastructure amidst histories of slave trade and mercantile networks. The curatorial collective Freethought contributed an anecdoted archive on exhibition reception and conversations around the exhibition as a space of transcontinental solidarity, through examples that lie beyond the canon of ‘great’ exhibitions.10

The Ghetto Biennale in Port-au-Prince, organised by Leah Gordon and André Eugène, as well as the ‘radical publicness’11 of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, with which I am more familiar, are recent models that genuinely push us to consider how to dismantle the social hierarchies entrenched in biennial institutions around the world. The gestation periods of these initiatives in the Caribbean and in India have been marked by the close involvement of local stakeholders in defining the parameters of an open-form praxis in communal engagement.

My involvement as curator of the small-scale Contour Biennale 8, Polyphonic Worlds: Justice as Medium, presented between March and May 2017 in Mechelen, Belgium, has shown me the immense value of working closely with participating artist and curatorial collectives such as Karrabing Film Collective, Council, Ritu Sarin, Tenzing Sonam and Agency, all of whose practices have developed transversally amongst circuits beyond the art world, in environmental activism, cinema and legal advocacy. Contour 8’s exhibition venues included a historic court building, where the biennial exhibition and public discourse tackled the media archaeology of law-making and juridical infrastructure, the performativity of the trial, the artist as witness and the ongoing struggles for social justice that contest the ruling matrices of state power and right-wing authority.12

To Tsing’s statement on sensing precarity, I would add Leela Gandhi’s call for ethical enterprises that operate through informal and collective practices, remaining alert to counter aggressive cultures of imperialism and fascism. In a mutating ethics of connection13 that remains subjective and nonconformist, the biennial ‘medium’ could perform as a terrain that finds utility in shifting forms of knowledge and responds to the shared vulnerability that has now taken on a planetary scale.

Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam, Burning Against the Dying of the Light, 2015–2017. Exhibition view of Contour Biennale 8, Polyphonic Worlds: Justice as Medium, Mechelen, 2017. Photo: Kristof Vrancken. Courtesy of the artists and Contour Biennale 8.

Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam, Burning Against the Dying of the Light, 2015–2017. Exhibition view of Contour Biennale 8, Polyphonic Worlds: Justice as Medium, Mechelen, 2017. Photo: Kristof Vrancken. Courtesy of the artists and Contour Biennale 8.

NOTES

1 Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at The End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015, p. 20.

2 Modern Monsters/Death and Life of Fiction: Taipei Biennial 2012 Guidebook, ed. Anselm Franke, Taipei: Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 2012.

3 See Chihiro Minato’s exhibition presentation, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UzCWCtu_ kWY

4 Chihiro Minato, “How to Catch a Beast—A Brief History,” Taipei Biennial 2012 Journal, 2012, https://www.taipeibiennial.org/2012/en/journal/27.html.

5 Henri Lefebvre, Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life, New York: Continuum, 2004, p. 51.

6 The Museum of Rhythm, ed. Natasha Ginwala and Daniel Muzyczuk, Berlin and Łódź: Sternberg Press and Muzeum Sztuki, 2018.

7 Rhythm Figures was realised as part of Manifesta Journal’s Online Residency Programme on the invitation of Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, http://www.manifestajournal.org/online-residencies/natasha-ginwala.

8 http://msl.org.pl/en/exhibitions/archive-exhibitions/the-museum-of-rhythm,2175.html

9 http://www.council.art/residency/760/within-infinite-ear.

10 http://freethought-collective.net.

11 Natasha Ginwala, “Kochi-Muziris: Biennale as South Asian Form,” Marg, 68: 2, December 2016-March 2017, pp. 14-21.

12 http://contour8.be/en/about.

13 Leela Gandhi, “Utonal Life: A Genealogy for Global Ethics,” in Cosmopolitanisms, ed. Paulo Lemos Horta and Kwame Anthony Appiah, New York: New York University Press, 2017.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Natasha Ginwala is a curator and writer. She is curator at Gropius Bau, Berlin. Ginwala curated Contour Biennale 8, Polyphonic Worlds: Justice as Medium and was curatorial advisor for documenta 14 in 2017. She writes on contemporary art and visual culture.