NEVENKA ŠIVAVEC & GERARDO MOSQUERA

Looking Beyond Hegemony: Graphic Arts and Curatorial Relevance

- 17.12.2018

The graphic arts — an ungovernably evolving range of practices — have significantly, if often without acknowledgement, contributed to the development of biennials. Historically, graphic arts biennials mobilised and sustained fr/agile networks for the circulation of works and ideas outside dominant Western networks.

In this conversation, Nevenka Šivavec, director of the Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana, Slovenia (the world’s oldest existing biennial exhibition of contemporary graphic arts, founded in 1955), and Gerardo Mosquera, curator of the 4th San Juan Poly/Graphic Triennial (2015), discuss their recent projects and challenges while sharing their views on the ongoing relevance of graphic art as contemporary art.

GERARDO MOSQUERA The San Juan Poly/Graphic Triennial has a long history: it is the fourth-oldest ‘perennial’ in the Americas. Launched in 1970 as a Latin American graphic arts biennial, it ran until 2002. In 2004 it became a triennial and headed in a different direction. Curated – and created – by Mari Carmen Ramírez, the first triennial sought to approach graphic media as expanded practices contributing to the field of contemporary art rather than as ends in themselves. Ramírez defined these expansions as “poly/graphic strategies for the multiple image.” The triennial shifted away from traditional printmaking’s emphases on technē and the matrix toward the visible impression, regardless of its origins.

This realignment reflected contemporary transformations of the graphic arts into one of the many instruments employed by artists to communicate their ideas. Graphic arts have exploded and hybridised promiscuously, becoming what we call contemporary art. Taking this further, we can now speak of post-graphics much as we speak of post-photography: as an expanded, decentralised, inclusive, operational notion beyond medium-specificity.

The fourth edition of the triennial, which I curated in 2015, emphasised decisively the notion of ‘poly,’ affirming the poly/ graphic nature of the event. Entitled Displaced Images / Images in Space, it stepped radically into the expanded field – the foundational concept of the triennial – to explore the displacements of the graphic image into a range of areas, supports, histories, habits, meanings and hybridisations, and into three-dimensional space. I may have gone too far: the exhibits were quite unlike what is usually expected of a graphic arts event. Luis Camnitzer even told me: “The triennial is great, but it’s not about graphic arts!”

In addition to traditional printmaking articulated in an expanded field, it did include works that might be defined as paintings, sculptures, performances, videos, photographs or combinations thereof. Yet their common denominators were the multiple displacements of the graphic image and technological reproduction. This led us out of the gallery and into the streets: the event had a notable presence in public space, while the triennial’s website presented a virtual interactive exhibit of memes. However, traditional printmaking articulated in an expanded field was also included.

By doing all this, I was trying to meet the present. We live in the age of the image… the displaced image. Its current ubiquity has led to both its manifold transformation and its amazingly dynamic intensity. The spontaneous production of images has become “a natural way of relating to other people,”1 as Joan Fontcuberta has noted, while much of our existence takes place around screens. In this context, we realise that displacement is the essence of the printmaking tradition. Prints entail the transfer of images from plates onto supports, transforming images in the process. Perhaps the fourth triennial wasn’t so radical in the end.

NEVENKA ŠIVAVEC When I got involved professionally with the Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana in 2011, I came across Rachel Weiss’ review of the sixth Havana Biennial published in Art Nexus in 1997. A footnote in her text caught my attention. Advancing “the idea that the biennial enjoyed a rebirth with the advent of postmodern notions of globalization,” she swiftly enlisted the Ljubljana Biennial to stand in for a motley group of globalisation detractors, relegated to the margins for their formal orthodoxy and their abstinence from the art-market-critical complex, stating:

For reasons of brevity, I am not taking into consideration the various other ‘margin’ biennials, such as that in Ljubljana, which have occurred over the years, both because their ambitions seem to have been more circumscribed formally and because they never really weighed in to the large international market and critical circuits in a significant way.2

Locally, the assessment of the Ljubljana Biennial was completely different. In the former Yugoslavia, it held an almost mythical position since its establishment in 1955. It was the first exhibition to demonstrate Yugoslavia’s specific historical and political advantages: thanks to Yugoslavia’s critical position, the exhibition could act as a crossroads between East and West. The biennial was proud to stand for the autonomy of the printmaking medium, for modernism as socialist Yugoslavia’s official style and for an alternative form of internationalism.

The biennial was a flagship for Yugoslavia’s open foreign policy, acting as an undeniably powerful ideological institution. As an art meeting point and a window onto the world, the biennial held mythic status for non-Western artists. But the Ljubljana Biennial was, until the late ‘90s, caught in a nexus, subjected to the hegemonies of representation, academicism, the state, the Western modernist canon and the male gaze. Even today, it is dealing with the ever-present hegemony of the graphic medium.

In the context of Ljubljana, the hegemony of the medium means much more than form or medium. The hegemony of the graphic medium defined local and global perception of the biennial. It was partially responsible for the creation of the myth of the Ljubljana Biennial that is still very much alive in the printmaking scene. Locally, the printmaking scene remains under state control as conservative and neoliberal currents comfortably snuggle to disavow the consideration of the biennial as, simply, a contemporary art project.

The 25th edition of the biennial, in 2003, brought about a radical change in orientation. Curated by Christophe Cherix, who specialises in art prints of the 1960s and 1970s, it put the multiplied image in a broader social and political context, featuring artists’ books, posters, photocopies, fliers and art newspapers. In a different vein, The Event, the 29th Biennial of Graphic Arts curated by Beti Žerovc, chose to ignore its printmaking history to concentrate on the art event instead.

In hindsight, we realised that the decision to turn away from graphic arts completely had been counterproductive, because both printmaking and fine art prints retain unexplored potential and remain extremely relevant under cultural capitalism. For the next edition of the biennial, we made the strategic decision to reinvest in the specific qualities of the medium of printmaking. Interruption, the 30th Biennial of Graphic Arts, curated by Deborah Cullen (who curated The Hive, the third San Juan Poly/Graphic Triennial in 2012), returned without much ado to printmaking processes and their relevance to contemporary artworks.

The 31st edition (curated by Nicola Lees) successfully explored the sociopolitical characteristics of the graphic arts, particularly in relation to reproduction, publicity and community. Lees emphasised that the mobile image is fundamental to our contemporary information economy: “The rendering of the image in motion as it collides with the fixed parameters of the printed or marked surface establishes a precarious balance of forces between artworks.”3

Despite all these experiments with formats and different attempts to expand the notion of the graphic arts, the audience here in Ljubljana still nostalgically pines for more printmaking. The myth of the biennial and of its influence informed pedagogical approaches and academic structures, which still produce a large number of printmakers who feel excluded from the contemporary direction of the Graphic Arts Biennial and from any expanded notion of the medium. How would you deal with the dilemma?

GERARDO First, let me state that I do not consider traditional printmaking to be obsolete. That would be a childish modernist mistake. Moreover, the high degree of specialisation and sophistication that it has achieved is a legacy that should not be lost – not that we should preserve these techniques as relics, but because they are perfectly capable of producing valuable works, as artists continue to demonstrate.

Puerto Rico has hosted a graphic international event for a very long time because the country has sustained a lively tradition of graphic arts. In the fourth triennial, I did not want to ignore this fact, but wanted to reconcile it with the triennial’s concept by considering how traditional printmaking operates in an expanded field. Thus, we organised a Myrna Báez solo show, to which Mexican artist Tania Candiani reacted, in the same space, with a work that transformed the lines of the great Puerto Rican master’s prints into sound. It created a provocative interaction. We paid homage to a classic printmaker and simultaneously introduced an experimental work fitting the triennial’s theme.

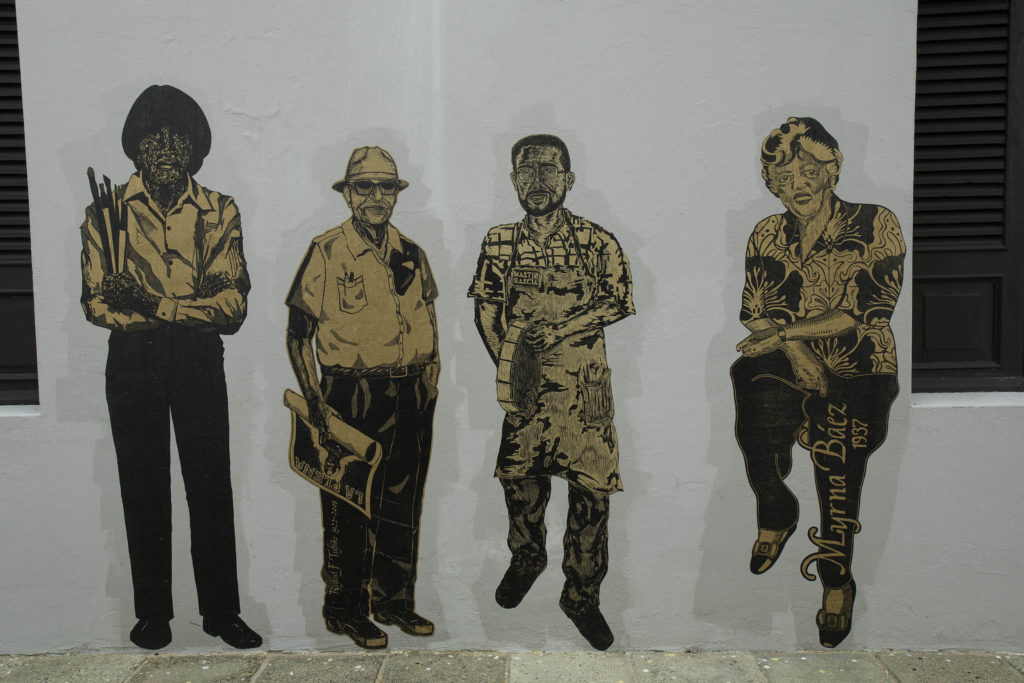

Another case was the expansion of the Grabadores por Grabadores project initiated by Rosenda Álvarez Faro, which had brought together a small group of young Puerto Rico-based woodcut artists who produced life- sized portraits of some of the island’s master printmakers, which were pasted up on a wall in Old San Juan. The triennial revisited this project, supporting some 30 local printmakers who did portraits of master printmakers of the Americas, which they installed on San Juan and Ponce streets, achieving a strong visual presence in these cities. So, we looked for common ground in a spirit of inclusion.

If you don’t mind, I would now like to move our conversation from the content of ‘perennials’ to their model, since I am very interested in the rhizomatic model, with artists at the curatorial core, that you envisaged for the latest Ljubljana Biennial. Could you please tell me about this approach?

NEVENKA This new approach may have been the consequence of exhaustion, after 15 years of endeavouring to sustain a biennial of graphic arts in both the local and the global contexts, and the persistent struggle for the right to think of the biennial in the post- graphic/contemporary condition. I absolutely agree with you that orthodox practices can create advanced and innovative art: some artists even respond to image hyperproduction by returning to the fundamentals of image reproduction. The problem is still (if I too may call on the words of Luis Camnitzer) that printmaking remains a colony of the arts.4

For our 32nd edition, I wanted to avoid discussions of printmaking and to focus on the event model instead. In today’s overabundance of curated perennials and other large-scale exhibitions competing for recognition, conveyed by the ‘capital’ of the selected curator, one detects a hyperinflation accompanied by a packaging of ideas, a stuttering of mannerisms and a reliance on illustration which make one doubt the potential of curatorial discourse, format and concept. The increasingly popular choice of assigning the curatorial role to an artist, an easy exit from the ‘crisis’ by biennial organisers, makes little difference. What remains problematic is the approach that instrumentalises the artwork, so that it becomes partial and inadequate, a voluntary prisoner of the theory, idea or headline. In comparison, traditional exhibition formats – one artist, one piece, one space and so on – seem auspicious again. The idea was to roll the dice in order to discover what was not expected.

I wanted to instigate a selection process led by the artists, which would somehow operate on its own. The inspiration for this experiment derives from notions of coincidence – betting on the unpredictability of group dynamics to form a paradoxical whole. The idea was further discussed and developed with a group of colleagues called the ‘biennial collective.’ The rhizomatic, organic structure was our wishful thinking; it would be pretentious to think that we succeeded in creating one, but the selections that artists made among themselves5 resists the hierarchical logic of the centrality of the curator and the narrative/illustrative bent of the curatorial concept.

Carlos Monroy Baphomet, One single birth made incarnate, 2017, multi-channel video installation. Installation view of Birth as Criterion, 32nd Biennial of Graphic Arts Ljubljana, 2017. Photo: Jaka Babnik. MGLC Archive.

Carlos Monroy Baphomet, One single birth made incarnate, 2017 Multi-channel video installation. Installation view of Birth as Criterion, 32nd Biennial of Graphic Arts Ljubljana, 2017. Photo: Jaka Babnik. MGLC Archive.

GERARDO I agree with you that we are experiencing a certain malaise as the curation of perennials is exhausting the too- centralised thematic model. I reacted to this in the 21st Paiz Biennial in 2018 – a small international biennial that has been taking place regularly in Guatemala since 1978 – which I am curating with no theme at all, or rather, with its methodology as its theme.

You have advanced further with your decentralised model, which opens a courageous and provocative experiment in the field. It is important to point out that approaches like yours in Ljubljana are not about avoiding curation: they look to open it up in new directions, a much-needed endeavour. Interestingly enough, radical and pertinent propositions in the field are taking place in events outside of mainstream ‘perennials,’ which sometimes provide freer and more productive environments, although they suffer from reduced visibility.

Pilar Quinteros, Cathedral of Freedom, 2015 Sculpture and performance. View of Over you/you, 31st Biennial of Graphic Arts Ljubljana, 2015. Photo: Urška Boljkovac. MGLC Archive.

Pilar Quinteros, Cathedral of Freedom, 2015 Sculpture and performance. View of Over you/you, 31st Biennial of Graphic Arts Ljubljana, 2015. Photo: Urška Boljkovac. MGLC Archive.

NOTES

1 Joan Fontcuberta, “Por un manifiesto postfotográfico,” in El arte en su des- tierro global, Javier Arnaldo and Eva Fernández del Campo, Madrid: Círculo de Bellas Artes, 2012, p. 92.

2 Rachel Weiss, “The Sixth Havana Biennial,” ArtNexus 26 (October-December 1997): 70-76, http://universes-in-universe.de/artnexus/no26/weiss_eng2.htm.

3 Nicola Lees, “Over you/you,” in grafični bienale/kratki vodič (Biennial of Graphic Arts 31/short guide), ed. Nicola Lees and Stella Bottai, Ljubljana: Medn- arodni grafični likovni center, 2015, p. 8.

4 Luis Camnitzer, “Printmaking – A Colony of the Arts,” in Text Archive of the Melton Prior Institute for Reportage Drawing, October 2006, http://www.meltonpriorinstitut.org/bilder/textarchive/2006/ Oct/2/text_56/attachments/camnitzer-engl.pdf.

5 The process was launched by sending a letter to the Grand Prize recipients of our last five editions. Each of these alumni was asked to invite an artist, who was then asked to propose another participant. The process was repeated for five rounds, leading to the presentation of works by 27 artists.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Gerardo Mosquera is an independent curator, critic and writer based in Havana and Madrid. He was a founder of the Havana Biennial, has curated many ‘perennials’ and exhibitions around the world, and published books and essays on contemporary art and art theory.

Nevenka Šivavec is a curator, editor and currently the director of the International Centre of Graphic Arts (MGLC) in Ljubljana, a museum specialising in print media and the main producer and organiser of the Biennial of Graphic Arts Ljubljana.