IARA BOUBNOVA WITH SYLVIE FORTIN AND BASAK SENOVA

Making the Best out of the Biennial Model

- 17.12.2018

Kutluğ Ataman, Küba, 2004. 40-channel video installation, duration variable. Commissioned by Artangel, London, 54thCarnegie International 2004/2005, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary (TBA21) Vienna, Theater der Welt, Stuttgart and Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney. Installation view of The Eye Never Sees Itself, 2nd Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art, Yekaterinburg, Russia, 2012.

In a far-ranging and considered conversation, repeat biennial curator Iara Boubnova reminds us of the golden age of biennials, in the 1990s, when the expanding practice of biennial making reflected a desire to change the field of contemporary art and shared a commitment to diversity, younger generations, experimental and critical art as well as peaceful coexistence. Today, other contemporary art constituents have appropriated some of the roles that biennials played initially, making it difficult for biennials to claim that they present contemporary art in a unique way. Yet, Boubnova stresses that biennials retain several crucial characteristics: they are producers and they connect people, while the brand name biennial enjoys considerable political currency and carries expectations of internationalism. Ultimately, the organisation of a biennial is a process of translation; it’s about tackling questions and difficulties that may not yet have proper translations, but for which the words, images and messages can be found.

Boubnova was recently selected to curate the Bulgarian National Pavilion at La Biennale di Venezia 2019, 20 years after her Venice curatorial debut, in 1999, in the same pavilion.

Kutluğ Ataman, Küba, 2004. 40-channel video installation, duration variable. Commissioned by Artangel, London, 54thCarnegie International 2004/2005, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York, Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary (TBA21) Vienna, Theater der Welt, Stuttgart and Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney. Installation view of The Eye Never Sees Itself, 2nd Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art, Yekaterinburg, Russia, 2012.

SYLVIE FORTIN Iara, you’ve been involved with biennials for quite a while, in different ways: as a biennial maker, in a governance role for Manifesta, as a biennial critical thinker and also as someone who visits biennials. With this vast experience, how would you trace the trajectory of biennials since the early 1990s? How have they developed? What have they become? Can we discern and theorise moments or crossroads in that development?

IARA BOUBNOVA In the 1990s, biennials were looked upon very positively. Expectations were high; there was excitement in terms of what they could achieve. Of course, there were many agendas. But the professionals’ main agenda was to demonstrate that contemporary art can unite people. And so, biennials began to take place in different parts of the world. A diversity of curators got invited, including younger people from different disciplines and backgrounds – not only experienced, well-known Western professionals.

Of course, political agendas differed in each place, city and country. Still, the professionals sought to change the field and shared a commitment to younger generations, to experimental and critical art and to peaceful coexistence. Biennials were to support a network of distinct localities, which the biennial brand would bring to greater awareness.

Later on, biennials became mega-shows, competing with each other and with other types of international cultural mega- events. In 2001, when I started to work for Manifesta in Frankfurt – which already saw itself in cultural competition with Kassel and documenta – the mayor of Frankfurt compared the future Manifesta with the Eurovision1 contest and the European soccer championship.

This sounds funny today. The 1990s were pretty optimistic times: everybody expected biennials to garner the same attention, publicity and budgets as other types of mega-event. Everybody, even politicians, somehow started to see art – at least contemporary art – as equal to sport in its ability to attract and unite people.

As political agents and cities got involved, biennials became mega-shows requiring superstars. This development shifted the idea of what biennials present. This is when, in my view, biennials somehow became both simpler and more complicated. The simple part was the presentation of superstars, artists who became famous in our times because of their market performance (sales prices).

The other, more complicated part was the discursive dimension: discussions, roundtables, artist talks, theoretical explorations and critical observations about exhibitions, art production and art languages. Some may define these theoretical, sometimes even academic, events as addressing local communities. Audiences for those two kinds of programmes are very different.

Mega-exhibitions – like the Istanbul biennial, for example – also began to spread around big cities. This dispersion made it complicated for audiences to experience and to understand the project. In my experience, in bigger cities, it’s nearly impossible to develop a language with which to present and discuss younger critical art (understood as projects that reflect contemporary society or, in their taking up of history, cast their inquiry into shared events).

As biennials increasingly featured personal exhibitions, they also started supporting bigger productions and allocating generous spaces and budgets to a few famous artists. In this, resources were taken out of the collectivity, diverted from mutual understanding and the mutual work of the biennials. In addition, we also now live in the era of festivals, which differ categorically from biennials, but are often conflated with them by stakeholders. Festivals rely on bigger publics; body count is their raison d’être. Festivals are sensational; biennials are more complicated. This is how I would trace the trajectory of biennials, although many events don’t follow this trend.

Today, as the context has become increasingly political, it’s more complicated. Other contemporary art agents have begun to appropriate some of the roles that biennials played initially. In addition, it’s difficult for biennials to claim that they present contemporary art in a unique way. Many galleries and other commercial institutions have now adopted event-like presentation modes.

One crucial thing remains: biennials are producers. This is the most fundamental dimension of the biennial brand. Biennials still produce better than other institutions. As the field of contemporary art shifts, biennials can give up some of their foundational principles but they cannot give up production. They must support the production of marginal artists.

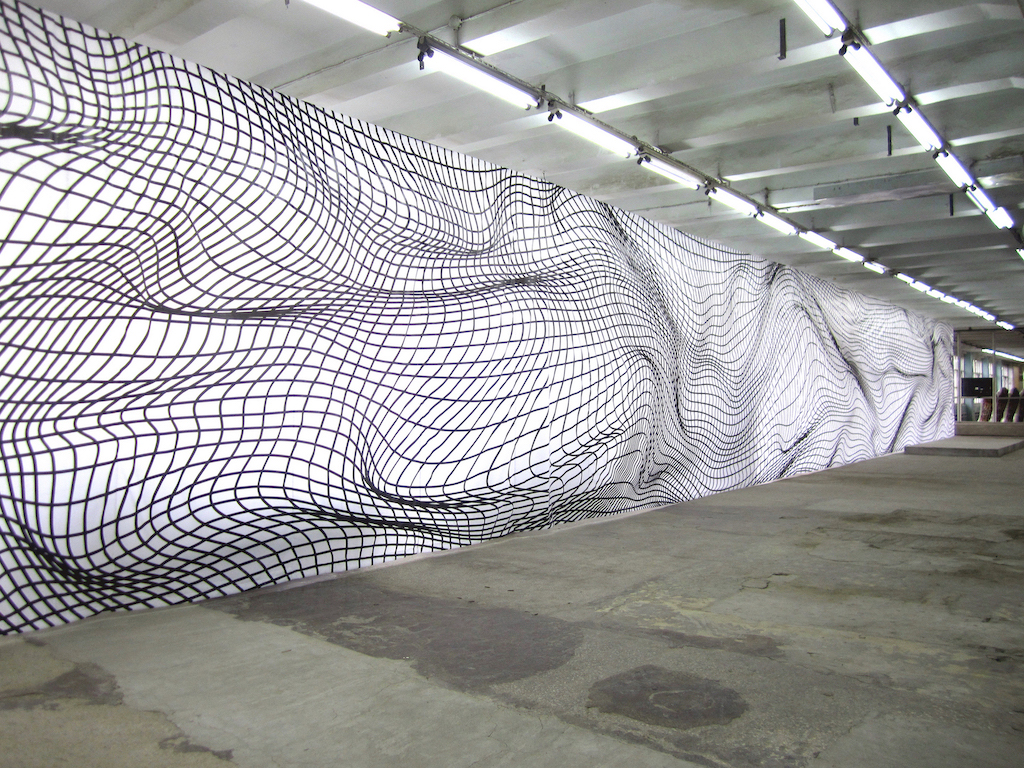

Société Réaliste (Ferenc Gróf and Jean-Baptiste Naudy) Windroad (detail), 2011 Installation. Dimensions variable. Installation view of The Eye Never Sees Itself, 2nd Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art, Yekaterinburg, Russia, 2012.

SYLVIE You are equating large cities with mega-events and festivalisation. You also say that biennials are producing institutions. Does this mean that production and thinking are now relegated to smaller cities, where artists live and work, whereas metropolises have been recast as sites of consumption? Are you drawing a parallel with other spheres of economic life, where sites of production and consumption have been redistributed around the globe?

IARA Yes, you’re going straight to the point, which is not so easy to explain. Of course, the biennial as a product, and as a type of event, is a very recognisable brand. In the 1990s, local politicians, even in our marginal situation, knew the implications of the word ‘museum.’ Today, many already know the word ‘biennial.’ They might only have an approximate sense of what a biennial is but they know that it’s a big flashy event that attracts different audiences, including, in the best case, international visitors. By supporting a biennial, politicians understand that they improve their position on the political and intellectual maps.

While many very small biennials may never make it onto the big map of events, their organisers use the brand name ‘biennial’ to advance their projects with local managers and politicians. For example, in Russia today, many very interesting events are named biennials even if they can’t always happen every second year. Spread around the country’s vast territory, these events attract many artists and draw local audiences but will never happen on a scale comparable with Istanbul, Moscow, Lyon or Venice.

Significantly, the biennial brand forces these smaller events’ curators and local managers to make their event more international or at least more open. This is very positive because local scenes are increasingly isolated and inward-looking. People need an international gathering. A biennial cannot only present local artists. The word biennial infers internationalism.

Organisers of smaller local events like to invite foreign curators, although not necessarily well-known people. They have very positive expectations from an interaction with someone who is not tied to local conditions. It may be something other than a conscious rejection of the over-consumerist conditions and context of big cities, or a struggle against global hierarchies of artists, curators and events. It may be an attempt to take the best from the biennial model: to provide opportunities for local artists to meet people who can discuss things on another scale; to introduce curators to dynamic art communities beyond market-driven cities like New York and London. Local events may still be able to use the trend for their own benefit, without serving the trend.

BASAK SENOVA Now, I’d like to focus on your work, Iara. I consider you one of the distinctive independent curators who have had the opportunity, strength and ability to transform the biennials and other organisations with which you have worked. Your projects have navigated significantly different ideological, curatorial or even art-based implications. How do you position yourself when you start to work with a biennial? I’d like to hear about your methodology and priorities, about what takes precedence when you negotiate a contract…

IARA The first and most important point, the methodological foundation, is to understand why a particular institution needs a biennial. Beyond words and manifestos, why do they want to make a biennial instead of a travelling show done by smart curator in a good museum with a nice collection, for example?

I believe in the idea that biennials connect people; they also connect modes of art production. Biennials provide the opportunity to explore problems and questions that can shape a particular local situation. They support artistic production, which museum exhibitions usually do not.

This search for balance between local phenomena and global implication is the first and fundamental reason for developing a biennial methodology. This doesn’t mean that important exhibitions require international or foreign involvement or that you can’t do locally important exhibitions. You can, but they are not biennials. The biennial logic is to search for intersections or conjunctions between the local and the global.

I try to understand what drives people’s desires to do a biennial. Do they understand that biennials are recurring events, designed from a long-term perspective? Are they ready to think beyond immediate, one-time success and to persist? If not, they are not thinking about a biennial, which must return every second year or third year, driven by the same idea of connections between the local and the global, through artists and their work, across different languages and aesthetic programs, by way of interactions between a curator and the locals. To develop a biennial is a little bit about translation: it’s about addressing questions and difficulties that may not yet have proper translations, but for which the words, images and messages can be found.

This is how I start to work. I don’t know if it is a methodology but knowing the motivation for a biennial is important. So is perspective. Sometimes, in places that are territorially or maybe culturally remote, biennials can deeply influence production. As local artists encounter works that they find interesting or, more superficially, successful, they may start to work in this direction sometimes unconsciously. This is not to say that they are copying or anything like that.

Biennial makers need to be aware of this possibility, which requires them to reflect on the reasons for their decisions. Biennials can’t just be about showing the most exotic, expensive or new thing. If a curator invites very important artists, they have to communicate that artist’s contribution to the project clearly: for example, her unique approach to problems or production methodology. They have to articulate why and how viewers can learn or understand something from the work. It’s also the grammar of the exhibition making which is for me very important insofar as biennials are supposed to involve many local people.

Biennials are also very good schools and educational opportunities, even if they are temporary. They help explain concepts like the autonomy of artistic production and artists’ rights. Biennials are supposed to teach ethics in the relations between money, politics and artistic production. Biennials are called on to do many things, which of course have to be redefined every time, taking into consideration the particular place where you are working.

Société Réaliste (Ferenc Gróf and Jean-Baptiste Naudy) Windroad (detail), 2011 Installation. Dimensions variable. Installation view of The Eye Never Sees Itself, 2nd Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art, Yekaterinburg, Russia, 2012.

Nedko Solakov, A Life (Black & White), 1998-2007 Installation-performance. Dimensions variable. Installation view of “History in Present Tense,” in Footnotes: Geopolitics, Markets and Amnesia, the 2nd Moscow Biennial of Contemporary Art, 2007.

BASAK What is your role in fundraising and shaping the budgets for your projects?

IARA Fundraising is not my strength. I’m ready to get involved in every stage of communication with potential funders. I’ll meet and explain the project while controlling their expectations. Often, if they extend financial support, sponsors expect to have influence and privileges. I’m ready to explain the limits and advantages of collaboration.

BASAK As an independent curator, what are your priorities? Do you have principles or rules when you are talking to potential biennial supporters or funders?

IARA It’s a very painful topic, maybe because we understand the connections between art and money differently. We already have another type of optics in the art field. It’s complicated because I know what it means to work in places where there is no support for art and cultural events. With every project, you have to start from nothing, and attract financial support.

Private support is tricky. Private corporate funds are risky, especially given their entanglement with globalisation, the military industrial complex and environmental irresponsibility. It’s about ethics. Ethics in business are very unstable, they are malleable and complicated. I have been thinking about the end of the long-term relationship between the Tate museums and British Petroleum in 2016. Would it be possible in my local context for a museum, and more specifically for museum publics, to successfully oppose this oil and gas money? I’m grateful that I don’t need to answer this question immediately. I don’t know how I would. My context counts very few powerful collectors of contemporary art. Their background is very complicated and shady. How to deal with dirty or totally non-transparent money? I don’t know.

From that point of view, I generally prefer when events are supported by public money, although I have no illusions about public money today. Public money is politically entangled in ways that are neither transparent nor clear. It is also somehow gathered and concentrated through channels of private capital. It’s difficult for me to imagine there is such a thing as perfectly clean money. Still, public funding somehow seems better, cleaner.

On the other hand, I believe that every offer of support for art and culture should be welcome to some extent. As a curator today, this means that you have to do more research into funding, almost as much as you research art, to develop relationships with people who support your vision.

Nedko Solakov, A Life (Black & White), 1998-2007 Installation-performance. Dimensions variable. Installation view of “History in Present Tense,” in Footnotes: Geopolitics, Markets and Amnesia, the 2nd Moscow Biennial of Contemporary Art, 2007.

Dan Perjovschi, Installation view of “History in Present Tense,” in Footnotes: Geopolitics, Markets and Amnesia, the 2nd Moscow Biennial of Contemporary Art, 2007.

SYLVIE Speaking of ethics, should curators contractually require significant input into the fundraising plan of the event?

IARA Yes, that would be right, but it’s not something that I would immediately insist on including in my contract because I’m afraid that there is no such thing as clean money. In some states, public money is connected with highly questionable, even unacceptable, state politics. However, I think biennials offer curators a stage from which to refine and question their understanding of the intersections of money and culture. It’s important to have it in mind.

BASAK Could you elaborate on your working methodology with artists? You have developed long relationships and collaborations with some artists. I value this. Do you produce works together? How do you approach this?

IARA I didn’t pursue a formal curatorial education. My training is in a very traditional approach to art history, which eliminates the individuality of artists. Art history deals with objects and categories – the artists of the Renaissance, of the Paris Commune, of the Russian avant-garde and so on. Curatorship is much more complicated. Its distinguishing characteristic is that it changes all the time; it’s always a profession in the making. With every project, you learn from society in general, from a specific, local society and from the artists. Relations with artists are important. They are also dangerous because artists can be very insistent and convincing. Artists who are important to you could influence your views.

In preparing for a bigger curatorial project, it’s most interesting to discuss its opportunities, beginnings and possible outcomes with artists. Not with theorists, academics, politicians, lawyers or others, but with artists. If a curator is attentive, she can largely avoid direct influences while being able to see things through the artists’ eyes. This is a very special position because artists are a privileged part of society, especially in poor socialist countries. Yet, they are not needed by anyone, for anything. They’re both in and out.

When I work with artists, I insist on the fact that they are citizens of a particular society. They have to be aware of what’s going on in their society and willing to discuss the logic behind various topics, approaches and motivations. From that I learn a lot. We can’t talk only about art for art’s sake or production.

It’s important for curators to support artists by sharing their point of view honestly, by discussing how the artist’s work is perceived from the outside. This may confuse and offend some artists but it’s important to confront one’s visions. Again, it’s about mutual understanding. This is also different from the ways in which an art dealer or a museum curator works with an artist. Biennial curators operate more contextually: they work to get the best, most timely project from every artist, while also selecting the best possible for themselves, as curators of a project. What do artists see? How do they read the visual world? I listen attentively and I ask a lot of questions, which often means that I end up in conflict with many of the artists.

BASAK You’ve been through several difficult situations. How do you position yourself if the organisers encounter a political or financial crisis while you’re implementing a biennial?

IARA It’s almost impossible to answer this question. You can meet a financial crisis with realism and modesty. I have experience working with artists in very modest financial conditions. In such contexts, the organisers have to be honest with everyone involved.

The organisers of artistic projects often tacitly expect participants to volunteer. I don’t agree with this practice, nor do I believe that this is how we should operate. If you can’t pay, you should immediately say so and explain why. You should also tell people why you need them. You have to provide a good explanation and value the person’s involvement, artistic or otherwise.

Political crisis? I don’t know how to answer. It’s good to orient yourself so as not to simply serve the momentous agenda of the institution that invites you. So you need to learn about the context, conditions and political situation. I deeply dislike situations when, having accepted an invitation to initiate a project, you discover that its outcomes are already planned. This is such a debilitating misunderstanding of a curator’s contribution. So many wonderful things are disabled from the onset.

Some political agendas are clear and would prevent me from getting involved consciously. Some are totally unclear. You need to deal with the latter in the logic of the project by supporting every critical approach of an artist, every political topic that exists today. Asking questions and listening to answers are our most important intellectual undertakings. Likewise, one of art’s most powerful contributions is to pose questions to society, communities and individuals, to tackle bigger scale problems.

SYLVIE In an interview about the Ural Biennial, you made an interesting related point. You theorised the venue as something more than a place, a building, an institution or a geopolitical history; you posited it “also as a specific audience, art tradition, and cultural policy existing at the moment and which the people aspire for.”2 I’d like you to speak about two things: first, this aspirational dimension of the venue; second, your folding of the audience into the venue when many curators think that they produce the audience, that the event produces its audience.

IARA I care about the specificity of the venue rather than its size. In today’s post-industrial society, there is an overabundance of buildings whose maintenance is challenging in terms of operations and finance. Those venues are often offered to cultural events, and art events in particular. It’s a trend that needs to be fought.

In the 1990s, when optimism about unification and its attendant quest for equality and parity of involvement was running high, we had a running joke about the divisions of Europe’s cultural map: in addition to many other lines, Europe was divided into places of red factories and those of Turkish bath houses. Their differences are already about audiences. The former factories and industrial plants, in large and small places alike, must draw industrial numbers of people as an audience. By contrast, bath houses, even the huge Roman thermae, produce more intimate relations. For me, the best venues are those where people still can see each other and not only art, which can be intimidating. They are places where we can talk with people, specific people, rather than with (generic) audiences or – even more scary – to audiences.

I don’t share the optimistic idea that curators, artists and cultural institutions produce audiences. Increasingly, audiences produce both events and art producers. Today, financial success and metrics-based accountability matter more than anything else. Meanwhile, it’s difficult to measure how ideas influence individuals or impact communities. So, we defer to number of visitors.

In this regard, the first Moscow Biennial (2005) is my most successful example. It was presented in the former Lenin Museum, in the midst of the city, behind Red Square. It was started by professionals who felt that Moscow needed an international exhibition. In fact, the first Moscow Biennial was the first international exhibition of contemporary art in Moscow, a city of 15 million people with a very developed infrastructure of private museums and collections and state institutions. But it was the place itself, more than anything else, that attracted people. In one month, we welcomed 300,000 visitors. Still, in a city of 15 million, 300,000 visitors is incidental. Every month, a shopping mall welcomes just as many people. How should we compare these attendance figures? How do we translate cultural attraction into the master narrative of accountability?

Different types of people and audiences come to a project when it is in time with its own society, bigger or smaller. Persistence is essential, which is an asset for biennials because they recur over time, they’re periodical. You can count on ongoing audience education. This may be why they are still so attractive, and not because they are expensive, big events with satellites. With each edition, a biennial is able to say something. People start to notice and to listen, to see and to respond. This response may not necessarily reach you today, but it will in its own time.

Dan Perjovschi, Installation view of “History in Present Tense,” in Footnotes: Geopolitics, Markets and Amnesia, the 2nd Moscow Biennial of Contemporary Art, 2007.

NOTES

1 The Eurovision Song Contest is an annual international song competition among the member countries of the European Broadcasting Union. Inaugurated in Lugano, Switzerland, in 1956, the programme is hosted by a different member country every year.

2 “Iara Boubnova: I just appreciate biennials in general,” interview with Iara Boubnova and Maria Kravtsova, blog of the 2nd Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art, 2012, http://en.second.uralbiennale.ru/news/ blog/2012/9/6/68.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Iara Boubnova is a curator of contemporary art projects. Born and educated in Moscow, she lives in Sofia, Bulgaria, where she is the founding director of the ICA-Sofia and has been Director of the National Gallery since 2018. Among her projects are the Bulgarian National Pavilion at La Biennale di Venezia 1999, Manifesta 4 (2002), the Moscow Biennial (2005, 2007), the 3rd Biennial in Thessaloniki (2011) and the 2nd Ural Industrial Biennial, Yekaterinburg (2012), for which she was awarded the INNOVATION Prize 2012. She is the president of the Bulgarian Section of the Association internationale des critiques d’art (AICA) and a member of the artistic advisory committee of MOCA China in Hong Kong, the Moscow Biennial of Contemporary Art, the Ural Industrial Biennial in Yekaterinburg and Autostrada Biennale in Prizren, Kosovo.

Sylvie Fortin is an independent curator, researcher and critic. She was Executive and Artistic Director of La Biennale de Montréal (2013-2017), Executive Director and Editor of ART PAPERS (2004- 2012) and Curator of the 5th Quebec City Biennial (2010). She is currently researching the currencies of hospitality.

Basak Senova is a curator and designer. She curated the pavilions of Turkey and the Republic of Macedonia at La Biennale di Venezia (2009 and 2015). She also co-curated the 2nd Biennial of Contemporary Art, D-0 ARK Underground (Bosnia and Herzegovina), curated the Helsinki Photography Biennial 2014 and the Jerusalem Show VII, Fractures (2014), and served as Art Gallery Chair of ACM SIGGRAPH 2014 (Vancouver). She is working on the CrossSections project in Vienna, Helsinki and Stockholm (2017-2019).