Maria Thereza Alves

Wrestling Space

- 02.12.2020

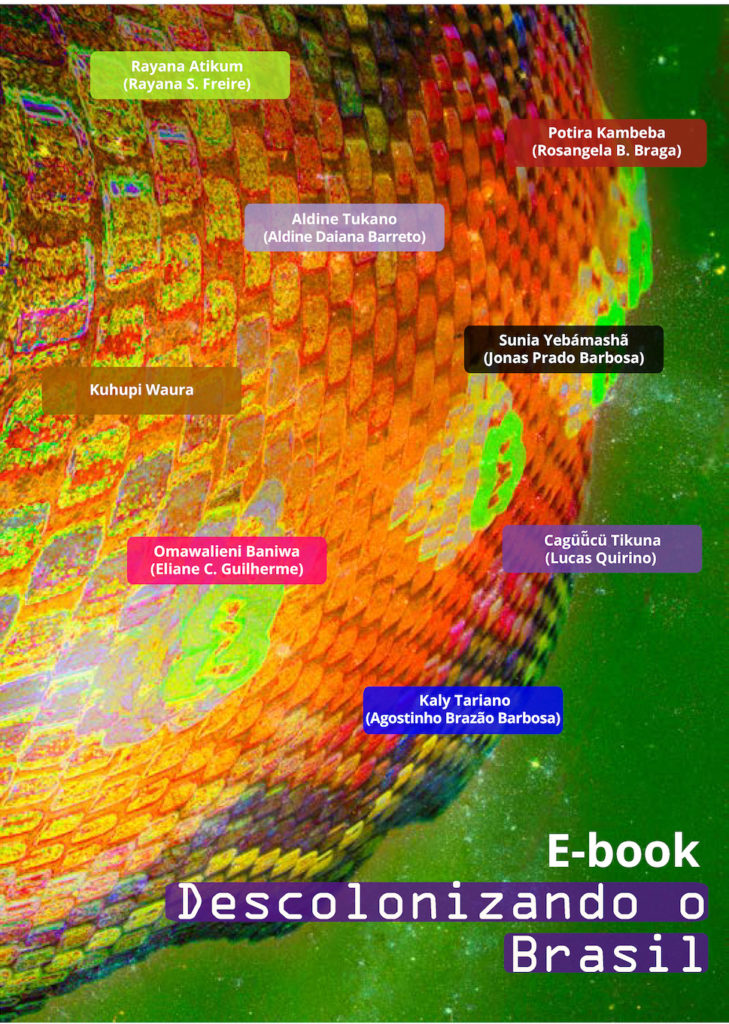

Maria Thereza Alves, A Full Void (detail), 2017. Installation: ceramic vessels installed throughout the city of Sorocaba. Exhibited at the Frestas Triennale, Sorocaba, São Paulo. Photo: Maria Thereza Alves. Courtesy of the artist.

I have been in several biennials. For this essay, I begin with the first biennial in which I was invited to participate, letting interconnecting thoughts trace a path to some of the later biennials. Consider it Part One of a longer essay yet to be written

I had just graduated from Cooper Union and was living in Harlem on the Upper West Side of Manhattan when I was invited to the second Havana Biennial by the curator Gerardo Mosquera. The Biennial was showing works of artists from Asia, Africa, and the Americas who were making art that reflected our realities in ways that were not so easy to see in New York.

Maria Thereza Alves, A Full Void (detail), 2017. Installation: ceramic vessels installed throughout the city of Sorocaba. Exhibited at the Frestas Triennale, Sorocaba, São Paulo. Photo: Maria Thereza Alves. Courtesy of the artist.

In the sculpture For America (1986), Juan Francisco Elso Padilla cast the Cuban poet José Martí as a liberation martyr. His head and shoulders are as finely carved as a statue of a European saint, while his earth-covered torso recalls earth-covered African sculptures upon which blood is poured as an act of sacrifice. In contrast to his head, Martí’s legs and feet are roughly hewn, challenging his attempt to keep walking through a field sprayed with darts. His raised sword is too short and thin for the battles for liberation that lie ahead. Many darts pierce his martyred body. By experimenting with Indigenous and African techniques, Elso, a Cuban artist of Spanish descent, began a dialogue between histories of colonisation and attempts at decolonisation in Latin America, calling on our entwined histories of indigeneity, slavery, and colonial settlement, and our quests to transform our political, social, and economic realities.

At that time, white-cube galleries in New York were mainly exhibiting work by European/American men concerned with theoretical questions specific to the canon of Western art. They spoke to a small world within their small circle; their ideas and works had nothing to do with my history, and I had nothing to with theirs. On the Lower East Side, however, artists pursuing art beyond the European settler discourse, such as Juan Sánchez, Ana Mendieta, Faith Ringgold, Jimmie Durham, Howardena Pindell, and David Hammons, were beginning to show their work at independent spaces like Kenkeleba House. Run by Corrine Jennings and the artist Joe Overstreet, this gallery’s mission was to show the work of artists of colour.

Maria Thereza Alves, Mismisidade del Mismo o Viviendo com Diez Dolares al Mes (Sameness of the Same or Living on Ten Dollars a Month), 1983 Black-and-white print, 14 x 11 inches. Exhibited in 2nd Havana Biennial. Photo: Maria Thereza Alves. Courtesy of the artist.

Maria Thereza Alves, Mismisidade del Mismo o Viviendo com Diez Dolares al Mes (Sameness of the Same or Living on Ten Dollars a Month), 1983 Black-and-white print, 14 x 11 inches. Exhibited in 2nd Havana Biennial. Photo: Maria Thereza Alves. Courtesy of the artist.

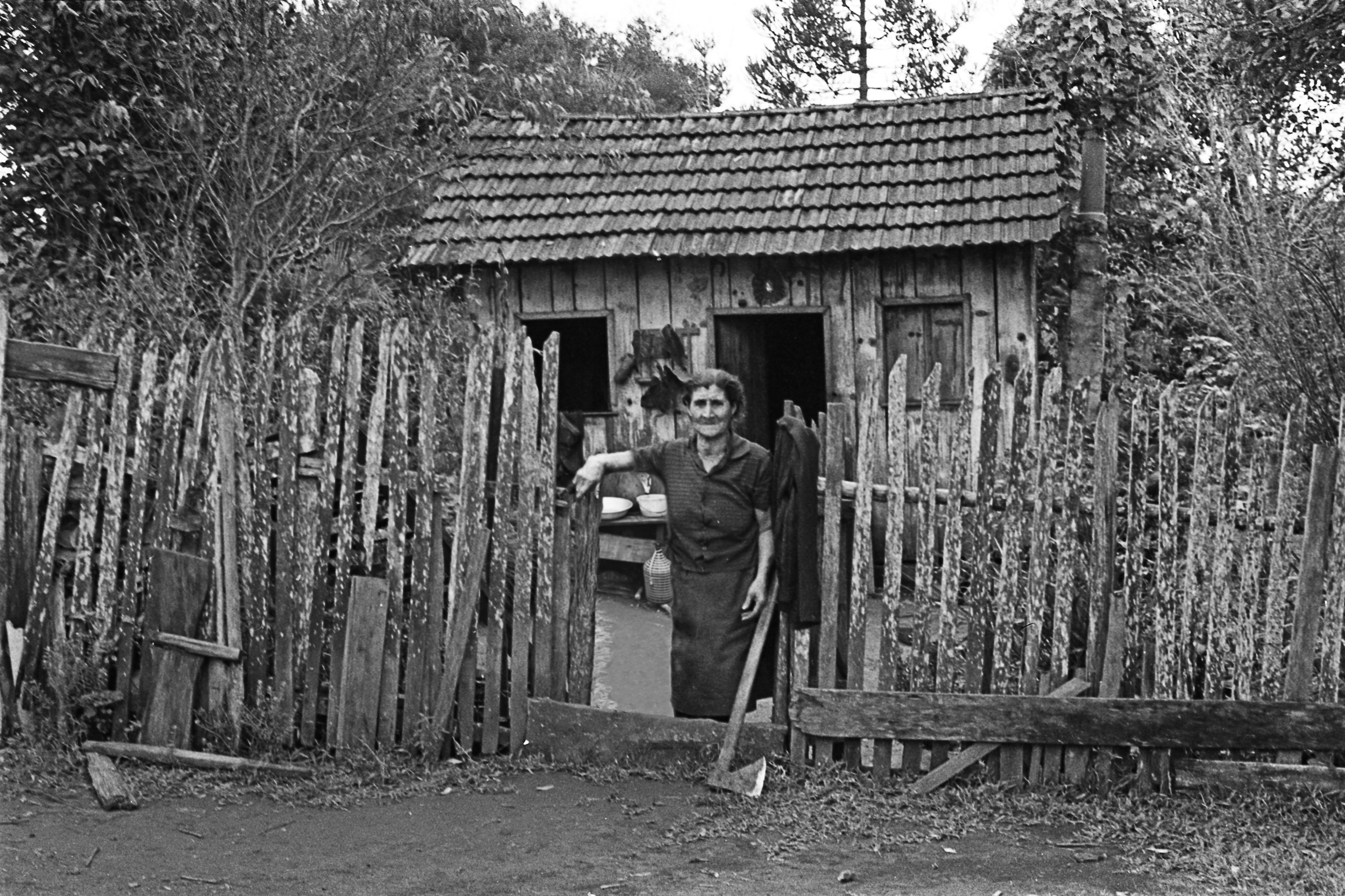

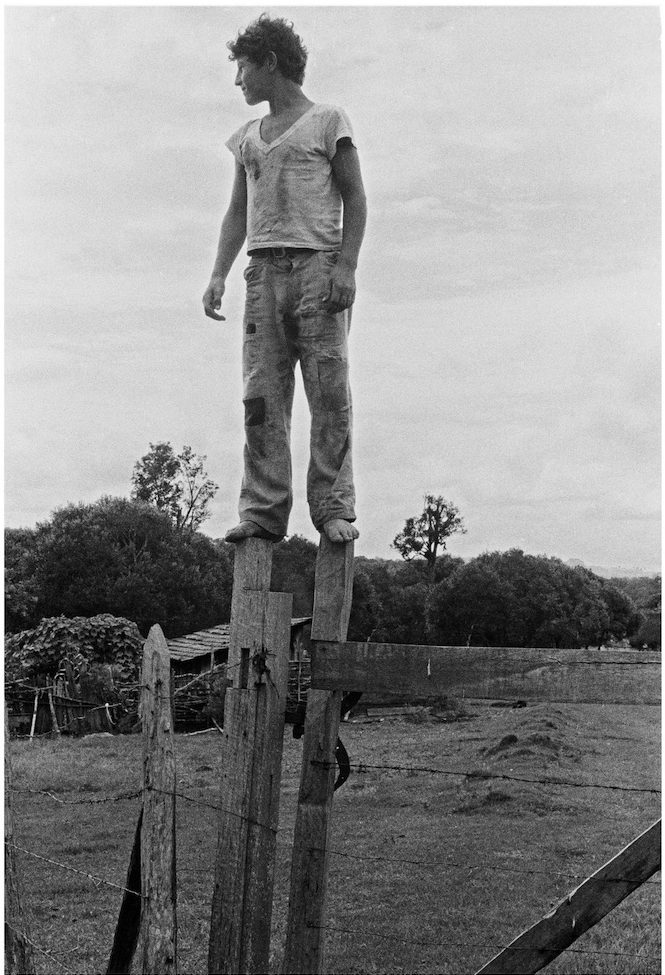

There in Havana was an entire biennial featuring artists who were addressing marginalised histories/stories through other ways of making art. For the Biennial, I made a black-and-white photographic triptych of the story/history—in Portuguese, “story” and “history” are the same word—of two of my relatives from my father’s village in southern Brazil.

The first image shows Sergio carrying an almost empty potato sack on his back. Fifteen years old at the time, he lived alone in the nearby forest, taking day jobs in the village to earn money to buy food. It had rained a lot that year, and there wasn’t much work. This is followed by an image of Vó Maneca, Sergio’s grandmother, who had raised him after his parents died. When she drank too much, she would try to drown him in the river. Vó Maneca had worked as a day labourer on local farms; by the time we met, her feeble body and arthritic hands only allowed her to quilt, which paid poorly. By then, Sergio was a strong and violent young man. He would come by to beat her, or, when she managed to close the door in time, he would attempt to destroy the chimney.

The last image is of Sergio standing on top of a fence post, triumphant and precariously balanced. Titled Mismisidade del Mismo o Viviendo com Diez Dolares al Mes (Sameness of the same, or living on ten dollars a month), this work was about the grinding poverty in this typical South American village where my father grew up, the dire lack of support from governmental institutions at that time, and surviving as best one could. It was a response to the Cuban Revolution’s iconography of the revolutionary peasant—brave women and men, arms in the air, courageously making change. But poverty crushes the soul and the body. Our histories/stories are usually inglorious, and our reality is one of despair and betrayal. I compiled our stories and photographs for a book entitled Recipes for Survival, which was published only recently—thirty-five years later. Sergio died at the age of forty following a knife fight outside a bar.

I participated in the Bienal de São Paulo in 2010 and 2016. I had not returned to Brazil in a long time, as I have a long-term love/hate relationship with the place. My work as a founding member of the Green Party of the state of São Paulo in 1987 was subverted after several of us left for different reasons, during a takeover of the party by conservative American-style evangelicals in the early 1990s. I do not have the space to discuss both editions of the Bienal here, so I will focus on the 2016 edition, for which I was commissioned by its curator Jochen Volz to make a new work entitled A Possible Reversal of Missed Opportunities.

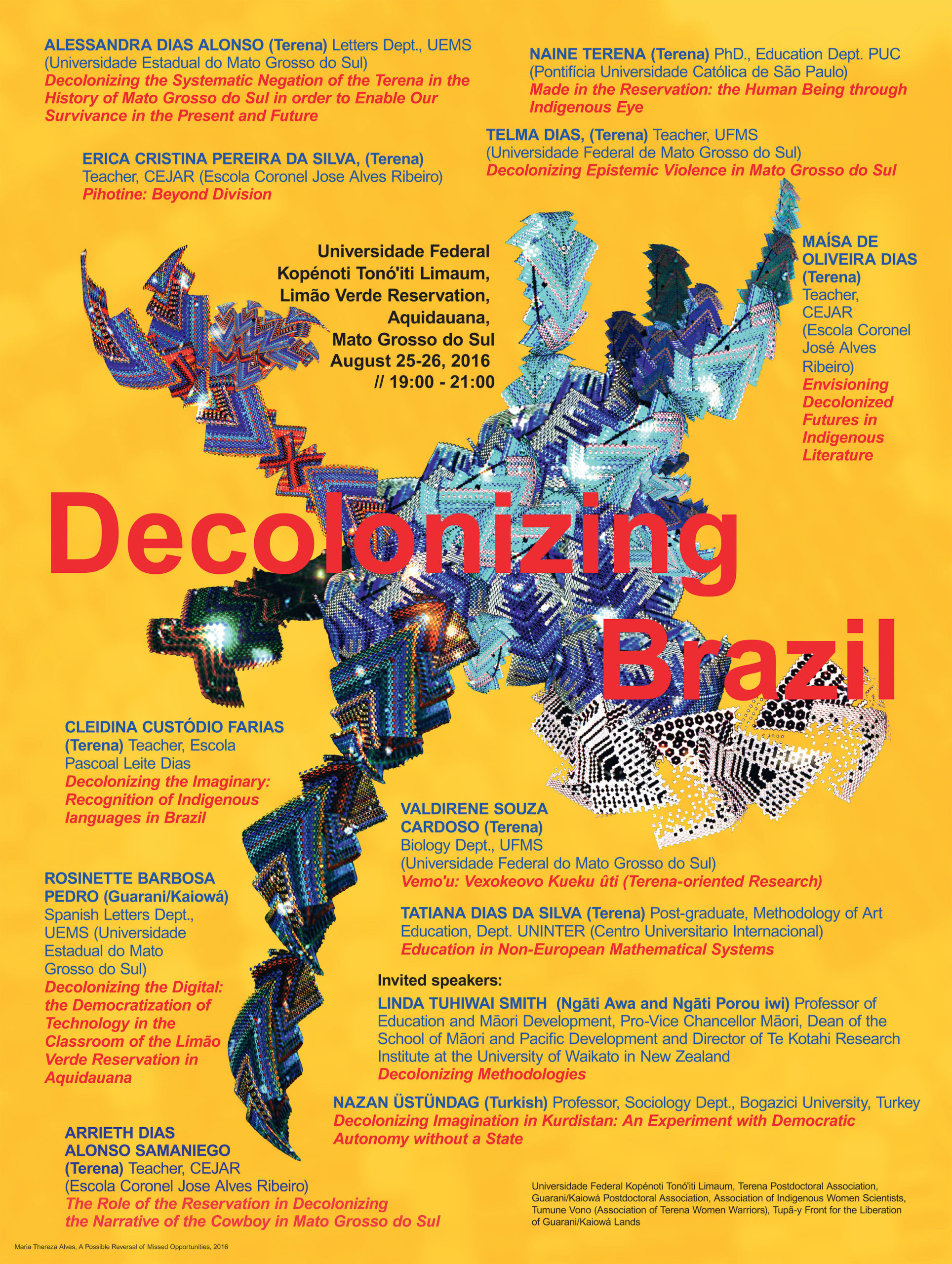

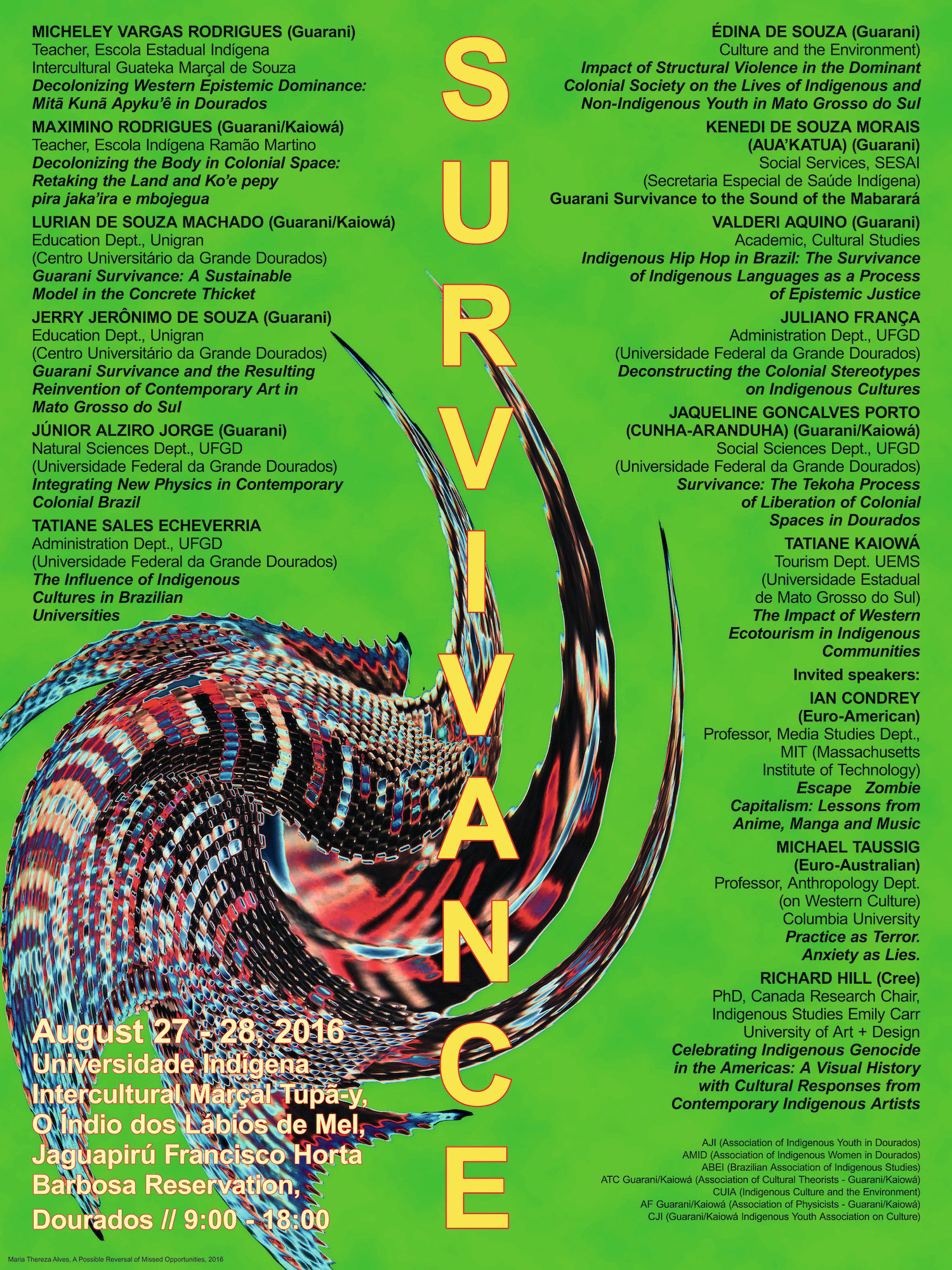

The starting point was the unrelenting exclusion of Indigenous voices in contemporary Brazilian society, denying Indigenous communities both agency and input in the making of a truly pluri-ethnic society. Only in the last decade or so have Indigenous students been welcomed in—or rather, not prevented from attending—institutions of higher education in some parts of Brazil. However, Indigenous languages are still not officially recognised and are therefore excluded from the curriculum. A Possible Reversal of Missed Opportunities began with three workshops that I conducted in Indigenous communities in Rio Branco in Acre and in Dourados and Aquidauana in Mato Grosso do Sul. These workshops led the Indigenous participants to propose a series of hypothetical conferences on subjects that were of interest to them. This work was thus conceived as a hypothesis inasmuch as the conferences were never to take place; it manifested as a series of posters advertising the conferences, which were distributed across the workshops’ host cities and displayed in universities, institutions, and other public spaces.

The posters announced events that had taken place a week before they were put up, giving the impression that the event had already occurred—that the conferences were a fait accompli. This allowed non-Indigenous people to take note of the discourse and exchange that are foreclosed by the exclusion of Indigenous voices from all fields of contemporary thought and civic life in Brazil. The Bienal coordinated the logistics for this work across three communities with several ethnic groups; it later provided funds to bring two representatives from each workshop to see the work and the exhibition in São Paulo. The poster work facilitated the establishment of networks between reservations, which had not existed before. While I was in Rio Branco, Soleane Manchineri, a participant who was also a student at the local university, invited me to visit her workplace, an association training Indigenous forest agents. I later returned there to work on To See the Forest Standing, and we are currently doing a fundraising campaign for them through Serpentine Galleries. Several other collaborations developed with the members of the Jaguapiru Reservation in Dourados. I will soon co-author an essay with Xanupa Apurinã, who has just finished her Bachelor’s degree in Rio Branco, where I met her while developing A Possible Reversal of Missed Opportunities.

We had an epiphany during a workshop in Limão Verde Reservation in Aquidauana, where the participants were mostly Terena: we should start our own university. We had initially thought of naming the local university as the venue for our hypothetical conference. But after their disappointing refusal to host our workshop, we decided we did not want to give them any credit for their lack of participation. Someone suggested that we found a university. This is when the Federal University of Kopénoti Tonó’iti Limaum came into existence, sponsored by the Terena Postdoctoral Association, the Association of Indigenous Women Scientists, the Association of Terena Women Warriors, and the Tupã-y Front for the Liberation of Guarani-Kaiowa Lands.

I had read about decolonising the imagination, but could not quite grasp how we might do it; this workshop taught us how. The energy was exhilarating, and the hopes for the future envisioned by these women were made visible that day. Edina de Souza, who participated in the last workshop in Dourados, asked, “Now how do we apply this working process to the return of our lands?” The development of this work for the Bienal gave me the opportunity to return to the Guarani community in Dourados, where I had last been in 1980, when I was eighteen, to speak to the Guarani leader and land activist Tupã-y (also Edina de Souza’s father). He became my mentor, and I sought his advice on the possibility of creating a pan-Brazilian Indigenous organisation. He told me that such an organisation had been founded a month earlier—in those days information travelled slowly and was often hard to find—and suggested that I continue to work on international support. Tupã-y was assassinated in 1983 for his denunciation of settler land theft.

Maria Thereza Alves, Tupa-y, 1980. Black-and-white print, 11 x 14 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Since our epiphany, I have remained friends with several of the workshop participants. I was able to nominate Naine Terena for the Vera List Prize for Art and Politics; she travelled to New York as one of the finalists. Since the Bienal, I have collaborated with Jaguapiru Reservation members Ke´y Rusú Katupyry and Verá Poty Resakã on local actions and on a commissioned work for the 2017 Frestas Triennale in Sorocaba in the state of São Paulo. A Full Void (2017) addresses the ongoing presence in the city of Indigenous peoples, whose rich history has been relegated to a few pots, funerary urns, and ceramic shards—the only artefacts to survive the near-total obliteration that followed European invasion—as if they belonged to some distant past. Katupyry and Resakã produced ceramic works inspired by the ceramics conserved in Sorocaba. I placed them, half-buried, in public places of historical importance to the city’s non-Indigenous settlers.

A three-day workshop with undergraduate Indigenous students of the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) soon became part of the work’s process, along with a ceramics workshop conducted by Katupyry and Resakã at Kallipety Reservation in São Paulo, at the invitation of Jerá Poty Mirim. Sesc Sorocaba (a private non-profit institution providing cultural and educational programmes as well as health services), which funded the Triennale, had asked whether the ceramics produced by the residents of Kallipety Reservation would be available to the public; I answered that they would not, and that it was a learning experience. This led them to ask why they should fund it. I appreciated their directness and honesty: it gave us all an opportunity for discussion. I explained that while the Guarani continue to produce fine basketry, their ceramic production has not survived five hundred years of systematic genocide. When fleeing for one’s life, one takes only what can be grabbed quickly and carried easily—baskets come along, ceramics stay behind. Thus, settlers are complicit in the destruction of ceramic-making among the Guarani. I made a case for the importance of funding a workshop that would encourage the revival of this important cultural manifestation. Sesc agreed and later asked me to develop other projects with the institution.

Maria Thereza Alves, Tupa-y, 1980. Black-and-white print, 11 x 14 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

The involvement of the Indigenous students from UFSCar in the artwork was an attempt on my part to introduce them to Sesc, and to facilitate future collaborations. I also thought it was important for these youths to have a safe haven when they left their university campus to come to the city. For me, this was the most important long-term outcome of the commissioned work. Afterwards, Sesc hired them to organise activities for Indigenous Day celebrations—a national holiday in Brazil, like the national holiday celebrating the Bandeirantes (literally “flag-carriers,” Portuguese settlers in Colonial Brazil who enslaved, raped, and committed genocide against Indigenous peoples whose lands and resources they illegally usurped)—and to give workshops and presentations. For projects of this importance, my process follows an initial premise, opening up to other possibilities. This puts an additional burden on the production team, which must secure funding for unknown elements that eventually become part of the work. The Frestas team were always supportive, and understood the complexities as well as the political and social implications of this work. They actively encouraged the process and were particularly attentive to their obligations to empower the Indigenous students.

Maria Thereza Alves in collaboration with Aldine Tukano, Cagüücü Tikuna, Kaly Tariano, Kuhupi Waura, Ñorõ Tuyuka, Omawalieni Baniwa, Potira Kambeba, Rayana Atikum, Sileia Tukano, and Sunia Yebámahsã, Descolonizando o Brasil (Decolonizing Brazil), 2018, website and installation: videos, performances, text, magazines in the languages of the participants, sound, and e-book. Dimensions variable. Presented at Sesc in Sorocaba, São Paulo. Courtesy of the artist and her collaborators.

Maria Thereza Alves in collaboration with Aldine Tukano, Cagüücü Tikuna, Kaly Tariano, Kuhupi Waura, Ñorõ Tuyuka, Omawalieni Baniwa, Potira Kambeba, Rayana Atikum, Sileia Tukano, and Sunia Yebámahsã, Descolonizando o Brasil (Decolonizing Brazil), 2018, website and installation: videos, performances, text, magazines in the languages of the participants, sound, and e-book. Dimensions variable. Presented at Sesc in Sorocaba, São Paulo. Courtesy of the artist and her collaborators.

After this work, the students said they would like to continue to collaborate with me on a book by Indigenous Brazilian thinkers on decolonisation. This new project was a result of our initial workshop, which had led us to grasp the dearth of publication of Indigenous voices in Brazil. For the 2016 Bienal de São Paulo catalogue, I sent an image of the mock cover of the imaginary book Decolonizing Brazil, listing contributions by Indigenous thinkers. This dummy cover was a statement of hope, in the spirit of my Bienal work, since the publication was not even on the horizon; but it became a reality two years later, thanks to the very generous financial and production support of Sesc Sorocaba. Ultimately, Decolonizing Brazil was realised as an installation and website with an e-book, performances, videos, as well as sound recordings, and magazines which were made in the languages of the students. For what may well be the first time in five hundred years, Indigenous languages were heard from loudspeakers on the street in front of Sesc.

The installation entitled Maria’s House was commissioned for the 22nd Sydney Biennale (2020) curated by the Australian Aboriginal artist Brook Andrew, following our wonderfully intense discussions of its significance for the Indigenous community. In 1983, I had gotten to know Maria, who was living in my father’s village, to which I returned as an art student with new writing and photography skills.

When I asked, “What do we want the world to know about us?”Maria replied, a photograph of herself with no kerchief on her head. She did not want foreigners to assume she had white hair just because she was old. As she arranged her hair, she proudly said, “I’m ninety-eight and I don’t have one white hair. It’s all black. The people here think I’m Italian because of my black hair and fair skin but I am Bugre, pure Bugre. That’s why I don’t have white hair.” Bugre, which means “monster,” is a racist word that is also used deliberately to de-ethnicise Indigenous peoples by lumping many different nations into one ill-formed “people,” thereby denying the rich diversity of their cultures and languages, and threatening their existence.

In the village, no one besides Maria would admit to being Indigenous. While my father is called Rouge (Red) and his best friend was called Bugre, Maria was the only person with the courage to publicly admit she was indeed Bugre. The racism in the village was such that neither Maria’s children nor her grandchildren admit to being Indigenous; Maria was the last person to assert her indigeneity. She resignified that horrible word into one that she claimed with pride.

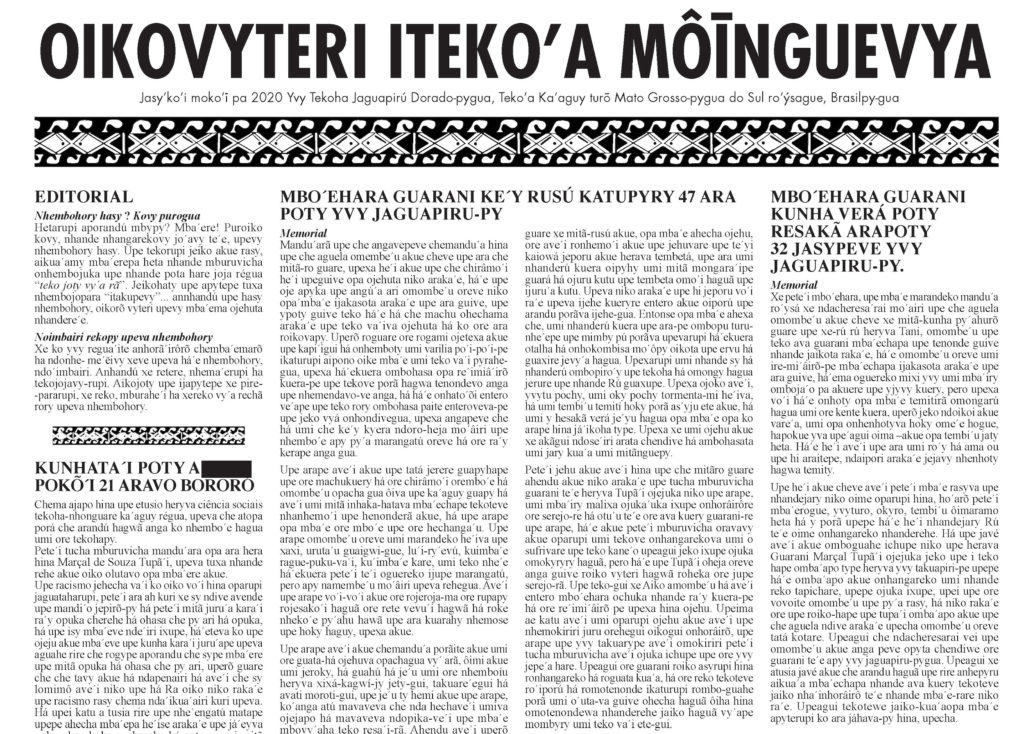

In 2018, her daughter gave me Maria’s house. Originally, my project for Sydney entailed its restoration. I hope that it will become a cultural centre, relocated to an area recognised as Indigenous land. So far, there has been no funding to restore the house or even take it out of storage. In the meantime, by decolonising our imagination, we have been able to found the Instituto Guarani-Nhandewá de Estudios da Historia do Brasil in the Jaguapiru Reservation in Mato Grosso do Sul. The publication of OIKOVYTERI ITEKO’A MÔINGUEVYA (Decolonisation continues), the first Guarani newspaper, edited by Katupyry and Resakã and translated into Portuguese, English, and Darug, is the first manifestation of the Instituto Guarani-Nhandewá and therefore of Maria’s House.

Instituto Guarani-Nhandewá de Estudios da Historia do Brasil and Casa da Maria (Maria Thereza Alves), OIKOVYTERI ITEKO’A MÔĪNGUEVYA (Decolonization continues), 2020, newspaper, 29 x 40 cm. Exhibited at 22nd Biennale of Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales. Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support of the artist and Open Society Foundations, and the kind assistance of the Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen. Courtesy of the Instituto Guarani-Nhandewá de Estudios da Historia do Brasil and Casa da Maria.

Instituto Guarani-Nhandewá de Estudios da Historia do Brasil and Casa da Maria (Maria Thereza Alves), OIKOVYTERI ITEKO’A MÔĪNGUEVYA (Decolonization continues), 2020, newspaper, 29 x 40 cm. Exhibited at 22nd Biennale of Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales. Commissioned by the Biennale of Sydney with generous support of the artist and Open Society Foundations, and the kind assistance of the Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen. Courtesy of the Instituto Guarani-Nhandewá de Estudios da Historia do Brasil and Casa da Maria.

While Brook Andrew was in São Paulo in 2019, we went to visit Jerá Poty Mirim on the Kallipety Reservation, where she explained her work on reviving the vast agricultural knowledge of the Guarani people, so much of which was obliterated by genocide campaigns. She has been travelling throughout Guarani territory from Espirito Santo in the North to Paraguay in the West and Rio Grande do Sul in the South, gathering maize—the result of millennia of experimentation and cultivation.

The kernels are now planted on her reservation. She explained, “This is my art.” Jerá founded the Kallipety Reservation, which is dedicated to traditional self-sufficiency through subsistence farming and the reclamation of Guarani farming techniques. Her teenage daughter is an artist who paints visions of her inner worlds on the doors and walls of homes on the reservation. Andrew had wanted to invite them both to Sydney but sadly funds could not be raised.

I had first met Jerá and Poty Poran in 2014 when I was making the video Artist as Bandeirante. The work was exhibited at the Casa do Povo cultural centre in São Paulo, where Jerá and Poty Poran were invited to speak. Although Jerá had wanted to collaborate in the 2016 Bienal work, she and almost everyone on the reservation had travelled to the coast for an important conference and would not return in time. Instead, she asked me to give a talk on contemporary Indigenous art, to be presented on the reservation. In 2019, Jerá Poty Mirim, along with Casa do Povo in São Paulo, received the Sotheby Prize to explore the place of the Indigenous in Brazilian culture and to develop an exhibit for the Kallipety Reservation. They shared the award with Naine Terena and the Pinacoteca de São Paulo for the re-examination of their collection.

For me, biennials have been opportunities to experiment with new ways of thinking about art and place while reaching a far wider audience than is often possible at museums and art centres. At the same time, biennials usually have resources to commission new works and to support artists who wish to undertake long-term collaborations. In turn, these collaborations can mobilise biennials’ networks and reconfigure them into opportunities to support and sustain marginalised voices, beyond the timeframe of any single biennial.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Maria Thereza Alves has participated in the Sydney Biennale (2020), the Toronto Biennial of Art (2019), Manifesta 12 (The Planetary Garden: Cultivating Coexistence), Palermo, Italy (2018), Sharjah Biennial 13 (2017), the 32nd Bienal de São Paulo (2016), the 8th Berlin Biennale of Contemporary Art (2014), the 29th Bienal de São Paulo (2010), documenta 13, Kassel, Germany (2012), the Taipei Biennial (2012), the 3rd Guangzhou Triennial (2008), Manifesta 7, Trento, Italy (2008) and the 2nd Bienale de la Habana (1986). Recent solo exhibitions of her work include El retorno de un lago at MUAC in Mexico City (2014) and the survey exhibition El largo camino a Xico (1991–2015) at CAAC in Seville, Spain (2015). Alves was the recipient of the Vera List Prize for Art and Politics for 2016–2018.

In 1978, as a member of the International Indian Treaty Council, Alves made an official presentation of the human rights abuses inflicted on the Indigenous population of Brazil at the UN Human Rights Commission in Geneva. Alves was one of the founding members of the Green Party of São Paulo in 1987.

Her recent books include Recipes for Survival (University of Texas Press, 2018) and Thieves and Murderers in Naples: A Brief History on Families, Colonization, Immense Wealth, Land Theft, Art and the Valle de Xico Community Museum in Mexico (Di Paolo Edizioni, 2020). www.mariatherezaalves.org