Raqs Media Collective

Afterglow Interview: The Making of the Yokohama Triennale 2020

- 04.12.2020

Eva Fàbregas, Tangles, 2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. Photo: Otsuka Keita

All images courtesy of the Organizing Committee for Yokohama Triennale.

Eva Fàbregas, Tangles, 2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. Photo: Otsuka Keita

All images courtesy of the Organizing Committee for Yokohama Triennale.

AS THE FIRST NON-JAPANESE ARTISTIC DIRECTORS OF THE YOKOHAMA TRIENNALE, HOW DID YOU APPROACH ITS INSTITUTIONAL EXPECTATIONS?

The invitation to send a proposal for the Yokohoma Triennale 2020 (YT2020) and the ensuing interview process prepared us to work with an institution that was seeking to redefine its modality and to position itself anew, with different priorities and protagonists. Certainly, the organising committee was looking for “incongruity,” a different way to imagine and execute the Triennale. This sense, which we registered, was not explicit, but it helped us shape the process and the momentum of the Triennale. Our initial research into the history of the Yokohama Triennale alerted us to the fact that its earlier iterations had engaged with conversations between Europe and Japan, conducted largely by male participants. While this is an important conversation, it is very specific: it needed to be (re)calibrated and fresh trajectories charted. This may have been the unstated expectation—or at least we thought so! And we were wholeheartedly committed to it.

Sato Risa, The Twin Trees (yellow) (blue), 2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. Photo: Kato Ken.

We begin our journey with a premise: the delineation of what we later termed the “perimeter of the self” with artists from Japan, in an attempt to discern the conversation that was sought out within its artistic milieus. We did this by diving into the archive of artist grants1 supporting long-term international mobility in order to find out what questions these artists were investigating. This was our way of sensing the specificities relating to the remembrance and narration of historical events, the extensions of geographical contours, the weight of institutional legacies, and the safety and convulsions of personal biography in the present moment in Japan.

We felt that a quiet upheaval was gathering. It shaped the attentiveness with which we tuned into ongoing conversations, and helped us mould the structure of YT2020: Afterglow.

Sato Risa, The Twin Trees (yellow) (blue), 2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. Photo: Kato Ken.

Nilbar Güreş, Unknown Sports Series, 2009. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Galerist, Istanbul. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

Nilbar Güreş, Unknown Sports Series, 2009. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Galerist, Istanbul. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

HOW DID YOUR RESEARCH PROCESS DEVELOP?

We embarked on this Triennale with a desire to find a fresh conversation connecting Yokohama, Japan, Asia, the Pacific region, Europe, Africa, and the world. Lantian Xie, an artist friend based in Dubai, pointed out that Nissan, the automobile manufacturer that claims to have changed the desert, is headquartered in Yokohama. This added to our growing sense that Yokohama has a specific imprint in the world.

We were discovering another Yokohama while reading Kimitsu Nishikawa’s philosophical ruminations in the book Yokohama Street Life. We enjoyed his easy and agile world making. Nishikawa was a day labourer at the Yokohama docks a few days each month, and on other days a raider of intellectual resources to construct world-images.

Lantian Xie, When I Move, You Move, 2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. Courtesy of Grey Noise, Dubai. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

Lantian Xie, When I Move, You Move, 2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. Courtesy of Grey Noise, Dubai. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

We began with a few intensive research trips within Japan, although we already had a sense of some of its non-urban areas because of our own artistic projects in Japan. The aims of these visits were to meet artists, to see exhibitions, to figure out the preferred forms of conversation in art milieus in Japan, to listen to talks, to find books in translation, to meet curators, and to visit the collection of the Yokohama Museum of Art. This helped us refine questions and possible trajectories; it also helped us devise a mode that would bring into play both discursive pressures and artistic concerns and impulses.

In our studio in Delhi, we invited a young artist, Kaushal Sapre, to look online for exhibitions, artist websites, commissions, and site-specific works and to carefully review the catalogues of earlier editions of the Triennale as well as the information provided by the committee. This gave us the background we needed to understand the demographics of Yokohama and visitors to the Triennale, and the range of discursive directions and geographical provenance of the artists and other participants in the previous Triennales.

Meanwhile, we started with walks in the Yokohama Museum of Art—there is no better way to know a space than to walk it, again and again. We were informed that the audience of the museum was above middle-age, with a very large number of senior visitors. Audience surveys seemed to suggest that the older generation of Yokohama residents enjoyed the museum’s programme the most. Our conversations with artists and curators suggested that the young preferred the music scene and gaming culture: it seemed that this demographic found art contexts overdetermined by pedagogical intent, while music and gaming cultures seemed to them less burdened and less hierarchical. This revealed a tension between the museum’s expectations and its positionings around art, inherited from its classical reverence of the modern canon. Clearly, we needed to chart a sharper trajectory of untamed sensibilities in our Triennale in Yokohama, while carefully calibrating reflections on other disobedient worlds. It was a deeply rewarding tightrope walk.

Eva Fàbregas, Tangles, 2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

Eva Fàbregas, Tangles, 2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

AMONGST THE FIRST TO REACH THE EXHIBITION PHASE UNDER THE UNSETTLING PANDEMIC CONDITIONS, WHAT DID YOU FIND NEEDED TO BE ADDRESSED?

We opened the Triennale on November 30, 2019 with the global release of the Sourcebook and performative actions at Episōdo 00,2 a two-day event held at the still metamorphosing Plot 48 in Yokohama, one of the three venues of YT2020. We were there with a number of the artists invited to participate in the Triennale and the Discursive Justice ensemble, along with the curatorial team of the Yokohama Museum of Art. By then, we had a fairly clear sense of the exhibitionary mode of the Triennale. Most of the works were on their final mile, and we were confident of the knots, itineraries, overlaps, segues, passages, compressions, and pauses that we were building into the exhibition. We also had extensive discussions with the exhibition architect, which were followed by more detail-oriented, material discussions in January. By then, the exhibition plan was almost final and work on procurement and shipping had begun.

Just before our visit of mid-March, by way of Hong Kong where Episōdo 01: Afterparty was to happen, the pandemic struck, interrupting the momentum. A few artists were struggling to meet their own expectations as they were finishing their commissions, and we were in touch with them regularly. Clearly, filming trips were no longer possible, some editing schedules needed to be reworked, and some printing plans had to be altered. Initially, we all thought Covid-19 would be like the SARS epidemic: After a few weeks of halted life, travel and gatherings would resume, even if skeletally at first. None of us thought that the total global lockdown would go on for months (years?), becoming our only reality.

Sarker Protick, Love Kill, 2014-2015. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. © Sarker Protick. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

Sarker Protick, Love Kill, 2014-2015. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. © Sarker Protick. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

Work remained virtually consistent. Daily meetings and discussions with artists and fabricators continued—surprisingly, perhaps—without hurry or complacency. Japan contained pandemic panic much better than many other countries. It quickly put protocols in place, and by the end of April preparations for the installation resumed in earnest, though on a reduced scale. In this extraordinary situation, artists were curious and cooperative, and slowly became confident that decisions were being made with care and understanding. We grew to realise that we most likely would be unable to travel to Yokohama ourselves to install the Triennale, which began to affect us. It did raise interesting questions, however, and we were open to potential answers. After meeting the mayor of Yokohama, the organising committee decided to go ahead with the Triennale, with all necessary precautions. We knew then that we were embarking on a very specific and special journey. We found ourselves tuning into a new state of awareness, akin to that which the mind enters to navigate an unknown thicket.

We intensified our online presence and worked through tough schedules, managing time zones and reconfigured work time. The on-site team scaled up their information sharing with more details, and did amazing work in communicating with the artists. May and June passed fairly quickly. During these months, the situation unfolding in Delhi was far more troubling, confusing, and stressful than the Triennale preparations: police investigations sought to attribute criminal culpability to the popular movements that had erupted a few months earlier, and the distress caused by the pandemic lockdown forced millions of people to walk across the country. In a way, the Triennale conversations with the artists about their artworks gave us a space to engage and be in the world in this highly stressful and in some ways truly dreadful time. We attempted to reflect this knotted time, with its new emotions and extended challenges, in the exhibition wall text:

We are now in the afterglow of an unfamiliar, viral, and partly unreadable time, and are without familiar protocols. Alone, and collectively, we have to navigate the oscillation of scales, quickened by the alteration in familiar rules. We are now immersed in a turbulent flow whose pressure rides through us all.

Renuka Rajiv, Cyborgs are Susceptible, 2016-2017, 2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

Renuka Rajiv, Cyborgs are Susceptible, 2016-2017, 2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

HAVING TO MAKE CRUCIAL DECISIONS FROM AFAR, WHAT STRATEGIES DID YOU DEVELOP?

The situation made us discover the effectiveness of conversations mediated by mobile phone cameras, which we and the team slowly mastered. We regularly did virtual walk-throughs of the site and discussed precise details. This needed some practice, as the lens on a phone camera adjusts light constantly, flattening space and light tonalities. These walk-throughs were conversational, querying, and exploratory as much as they were explanatory.

In Japan, the work culture is to follow a plan as much as possible. This was initially baffling to us, as we like working in a room with last-minute flexibility. But in this unfamiliar time, detailed planning was a reliable approach. We would have overlapping installation discussions, sometimes with the artists, and sometimes on our own. Almost all of the artists were consulted in every possible way about the installation of their work. In a way, the instructional mode became dominant over the intuitive and affective ones. But we trusted the judgement of our on-site curatorial team to communicate and discuss any slippage that we sensed. It was like working with many limbs inside a hologram—in the sense of the projection and interference itself.3

Elena Knox, Volcana Brainstorm (hot lava version), 2019/2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. © Elena Knox 2020. Photo: Photo: Otsuka Keita.

Elena Knox, Volcana Brainstorm (hot lava version), 2019/2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. © Elena Knox 2020. Photo: Photo: Otsuka Keita.

THE PHYSICAL EXPERIENCE OF THE TRIENNALE WAS PROBABLY SHARED BY AN UNUSUALLY SMALL NUMBER OF PEOPLE, AND ITS ONLINE EXPERIENCE AMPLIFIED. IN OUR DAILY LIVES, THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THESE TWO KINDS OF EXPERIENCE HAS BEEN REPOSITIONED. HOW DID IT IMPACT AFTERGLOW?

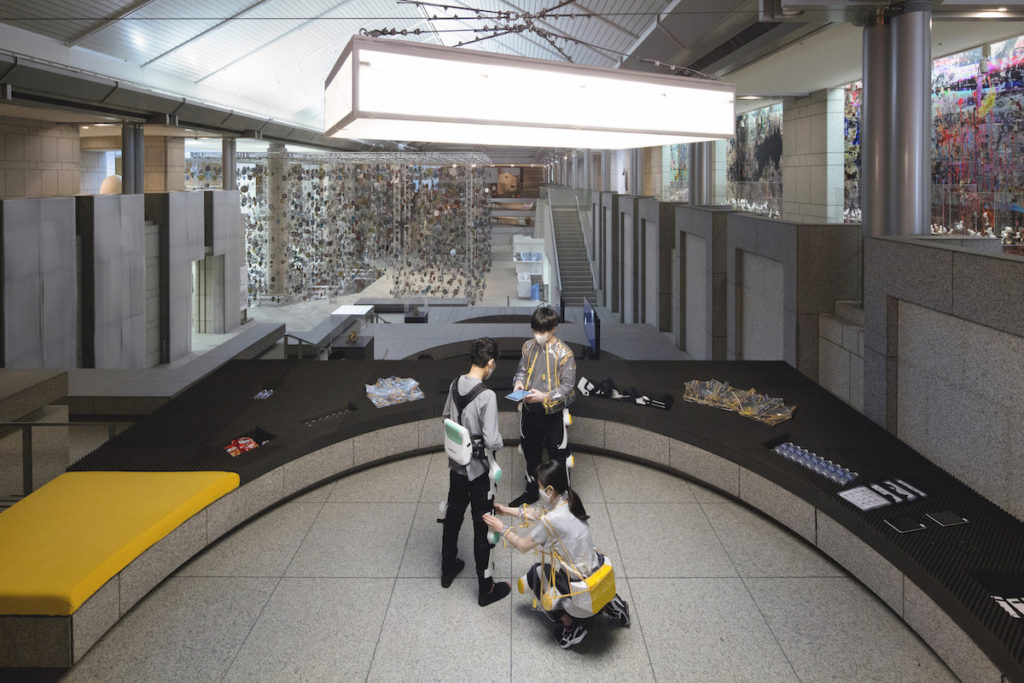

When YT2020 closed, we were happy to learn that, considering everything, Afterglow had been well-attended. Tickets were sold out on most weekends and people were willing to queue. Despite strict capacity restrictions, the exhibition still welcomed about 150,000 visitors. We had a moment of recognition of the vibrant conversation surrounding YT2020 in Japan when we spoke to students at the University of Tokyo. The sense we got from the conversation was that something lively had indeed been put in place, whether it was a “suspension of ideas” with which to feel and think the show or the sensation of being pulled into thinking the world in unfamiliar but intimate ways. That was reassuring.

By the end of March, we had begun to share with the Triennale team that the online, screen-based space could no longer be considered secondary and solely a zone for publicity. Many already knew this, but our changed world was going to make it the primary space for many visitors in Japan and for the global art public. Decisions made then helped us construct the online platform into an expanded space, making available new works by artists while providing Episōdo(s)with new online possibilities. The Discursive Justice ensemble experimented with forms of gathering, transmission, and relay in amazing and sometimes magical ways. The artists Yuichiro Tamura and Masaru Iwai insisted on elongated, dispersed, and unceasing modes of online presence. The “trans/actions” of Sure Inn group transgressed territorial and sexual borders with ease. These will be the sensibilities of the coming decade and we are delighted to have witnessed their germination.

Naeem Mohaiemen, JOLE DOBE NA (Do not drown in water), 2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. © Naeem Mohaiemen. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

WERE SPATIAL OR CONCEPTUAL RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN WORKS RECONFIGURED?

For Afterglow, we were working with two core premises: spectrum and suspension. These words, whether taken as conceptual anchors or as meta tags, carry both momentum and a (chaotic) drift. Take, for example, the idea of “care with toxicity” launched with Sourcebook in November 2019. This idea was a first strand in the weave of the sources we were working with. The troubled life of the toxic in the Indian subcontinent, with social structuration around banishment and untouchability, has been cruel and disastrous, and the world needs to find a way to engage with toxicity without falling into this same trap. In an essay we wrote in 2018, we argued that caring is to learn how to care with toxicity.4 The pandemic has made this question of care with toxicity urgent all over the world. The pandemic has changed the valence of both words, “care” and “toxicity,” and this had a tremendous impact on the ways visitors navigated the exhibition and engaged with the works. The pandemic reconfigured the relationships between the works for us.

Naeem Mohaiemen, JOLE DOBE NA (Do not drown in water), 2020. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. © Naeem Mohaiemen. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

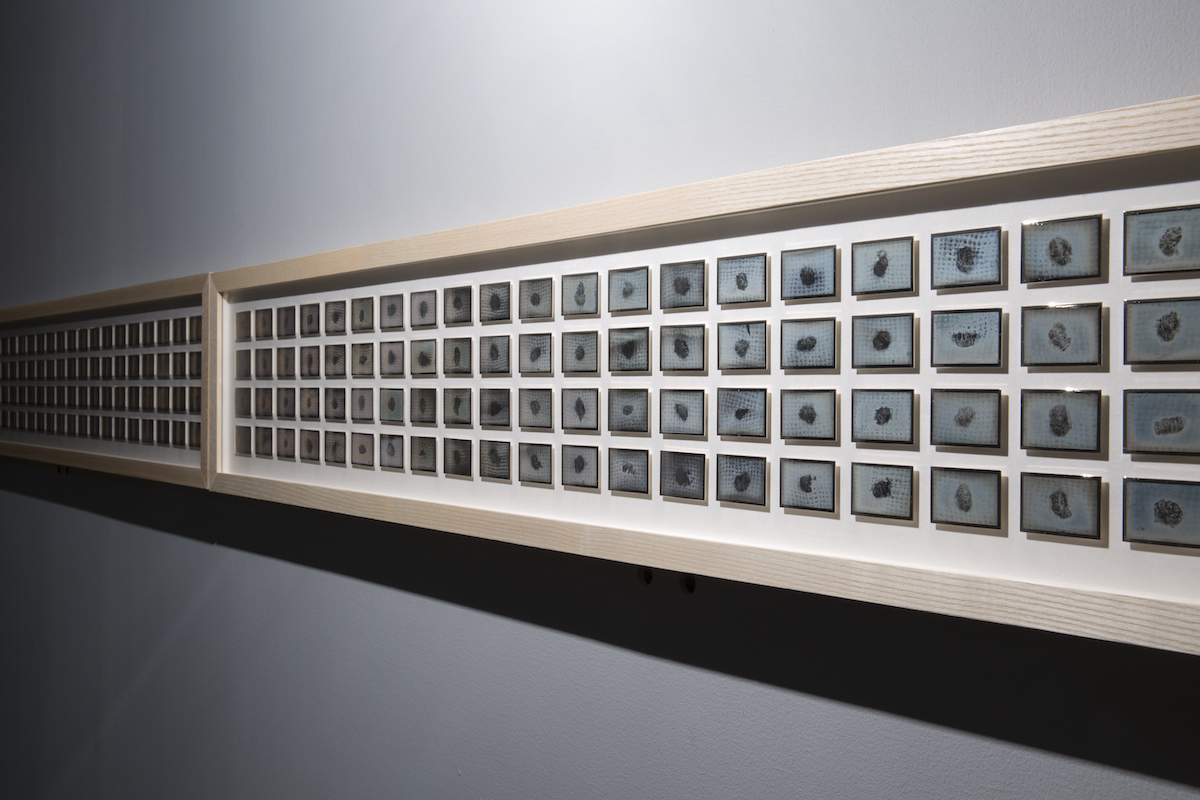

This sensibility (of spectrum and suspension) allowed for attention to the making of an exhibition that minimises the illustrative impulse of reading artworks. Instead, the exhibition arced towards creating a field of overlapping impulses and blurred contours. For example, Takashi Arai’s project5 undid the militaristic seizure of the collective bonds that are produced by making thousand-knotted vests for soldiers, which are now associated predominantly with the Second World War. These soldiers’ vests were embroidered by women in the family and the community. Takashi photographed each knot in meticulous square-inch daguerreotypes. We positioned his work next to Kei Takemura’s collection of everyday objects with broken joints, stitched together with bioluminescent silk thread. The break—the cut—becomes pronounced, not as a wound but as a radiant pathway to a sensibility of luminous care. Moving into the next room, visitors entered a darkened zone in which photo-structures were occasionally illuminated—and thus joined—by a moving light. Here, Lebohang Kganye connects unrelated worlds, reconfiguring them in an uncertain act produced by light. These works join intimate acts and large histories and potentialities with ease and reflexivity.

Lebohang Kganye, Mohlokomedi wa Tora (Lighthouse Keeper), 2017. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. © Lebohang Kganye. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

Lebohang Kganye, Mohlokomedi wa Tora (Lighthouse Keeper), 2017. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. © Lebohang Kganye. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

WHAT IS THE MOST SIGNIFICANT THING YOU LEARNED?

A significant thing we learned, or recognised again but differently, is that the triennial (or biennial) form is still an open structure. It needs to be investigated and defined anew with each occurrence. The biennial form plays a tremendous role not only in artistic milieus, but also in its porting of a plurality of complexities into a place to bring about a consideration of the world. This world making must be asserted and amplified in our discussions of the biennial form.

Biennials/triennials are expansive and productive engagements within artistic milieus; they also yield questions about forms and tendencies in exhibition making. Biennials inflect the question of the boundaries of art itself. They foreground possible solidarities and help overcome the limits imposed by dialects and comfort zones.

With this edition of the Yokohama Triennale, we learnt (again) that art has tremendous value as a site to think hard, with solidarity, and without succumbing to the urgencies created by the panic and incomprehension of the moment. Art asserts the possibility—always—of apprehending the world anew. It nurtures a space where not knowing need not be intimidating and where curiosity can be enjoyed.

WHAT CHALLENGES CONFRONT THE BIENNIAL FIELD?

These two years’ most important finding is the need to free the biennial from both the three-month duration it inherited from the museum exhibition tradition and its single-city fixation. In an isolation-seeking world, biennials are crucial and critical vectors of necessary transglobal conversations. For a biennial to play this role with confidence, it needs to see itself as part of a deliberative process: a conversation and a process that continue, persist, and proliferate beyond the “exhibitionary” moment. And it must do so structurally, by finding deliberative modes and technai. Further, it needs to involve others—all the other 150+ biennials—in this deliberation and to host possibilities for combinatory moves. By stretching the Yokohama Triennale 2020 in both its temporal and spatial dimensions, many more conversations and more excitement accrued around it, allowing different cities to breathe into the process and unexpected protagonists to meet.

Amol K. Patil, Reminiscent, 2019. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. © Amol K. Patil. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

Amol K. Patil, Reminiscent, 2019. Installation view of Yokohama Triennale 2020. © Amol K. Patil. Photo: Otsuka Keita.

WHAT WILL BIENNIALS LOOK LIKE IN THE (POST?)-PANDEMIC WORLD?

The art world’s response to the pandemic provides a good clue as to how post-pandemic biennials will shape up. Artists have shown immense courage and presence for each other. Hundreds of online gatherings and lateral conversations have taken place. These lateral gatherings are cooperative and convivial. In India, artists raised resources and were on the streets to help people in distress and to protest. By contrast, large art institutions have retrenched, laid off and furlowed people, and retreated into a search for timely thematics; they seem rather confused about their role in the world that is emerging.

Since the biennial works on the edges of the contemporary—always trying to grapple with the emergent—it will probably need to change the way it thinks about scale. Biennial events may need to move laterally, become mobile, and open themselves up to coalitions between cities and institutions, engendering more nodes and multiplying protagonists in order to intensify both “life.deliberative” futures and “trans.global” conversations.

NOTES

1 Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs (Program of Overseas Study for Upcoming Artists), launched in 1967. About 3500 artists have participated. There are six types of grant—for one-year, two-year, three-year, special (80 days), short stay (20 to 40 days), and high school student (350 days) courses, in the fields of media art, including fine art, music, dance, theatre, film, and stage design.

2 Yokohama Triennale 2020 launches Sourcebook and the Episōdo series.

3 “A hologram is a real world recording of an interference pattern which uses diffraction to reproduce a 3D light field, resulting in an image which still has the depth, parallax, and other properties of the original scene. A hologram is a photographic recording of a light field, rather than an image formed by a lens.” See en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holography.

4 Raqs Media Collective, “Raqs Media Collective Dreams of Equal Division of Toxicity,” Mint Lounge, 29 August 2018.

5 These works were titled Multiple Monuments for 1000 Women (No.1–10); A Multiple Monument for a 5 Senn Coin; Anti–Monument for 1000 Women and the Former Imperial Japanese Army Clothing Factory, Hiroshima; Silkworms’ Umwelt (A Further Construction), 2020, Yokohama Triennale of Art.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Raqs Media Collective was formed in 1992 by Monica Narula, Jeebesh Bagchi, and Shuddhabrata Sengupta. In several languages, the word raqs denotes an intensification of awareness and presence attained by whirling, turning, or being in a state of revolution. Raqs Media Collective takes raqs to mean “kinetic contemplation” and a restless and energetic entanglement with the world and with time. Raqs practises across several media, including installation, sculpture, video, performance, text, lexica, and curation.

From 2000 to 2013, Raqs spent time at Sarai—which they co-founded—at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) in North Delhi, where they edited the Sarai Reader Series.

Raqs’s work has been shown in museums and exhibitions around the world, including documenta 11, the Venice Biennale, the Istanbul Biennial, the Biennale of Sydney, the Shanghai Biennale, and Bienal de São Paulo; and in solo shows and projects at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi; Tate Modern, London; Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC), Mexico City; Fundación PROA, Buenos Aires; the Whitworth Gallery, Manchester; K21, Düsseldorf; and Mathaf, Doha, amongst others.

Curations by Raqs include The Rest of Now, Manifesta 8, 2011; Sarai Reader 09, Devi Art Foundation, Gurugram, 2012; Insert2014, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA), Delhi, 2014; Why Not Ask Again, Shanghai Biennale, 2016; In the Open or in Stealth, Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA), 2018; Five Million Incidents (Goethe Institut, Delhi and Kolkata, 2019–2020; and Afterglow, Yokohama Triennale, 2020.