Solange O. Farkas

Video, Art, and Activism: A Southern Perspective

- 03.12.2020

- Case StudyMedium-specific eventsSao PauloSolange O. FarkasPaulo NazarethAkram ZaatariJoana HadjithomasKhalil JoreigeGhassan SalhabGilbert HageLamia JoreigeMarwan RechmaouiWalid SadekJalal TouficWalid RaadRafael FrançaEder SantosIsaac JulienAurélio MichilesJonathas de AndradeRosângela RennóLeón FerrariSebastian Diaz-MoralesDaniel LimaMoisés PatrícioRosana PaulinoSerigrafistas QueerVirgínia de MedeirosTeresa MargollesAndrea Tonnaci

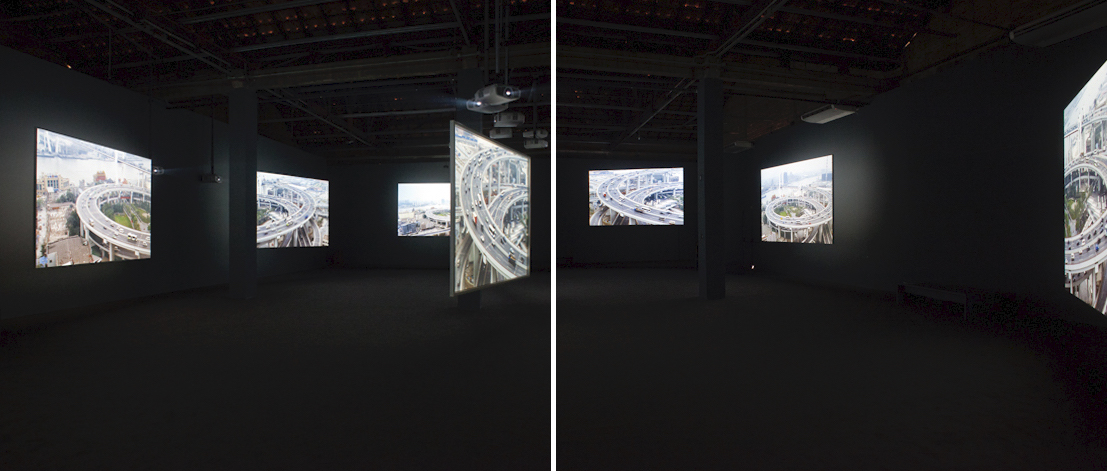

View of Imagined Communities, the 21st Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil, 2019. Photo: Everton Ballardin.

The more these many art accents of the geopolitical South encroach on the hegemony of the global-art language, the greater the cacophony they create, in clear defiance of said dominance. Striving to be heard in institutional spaces, in which hegemonies of representations of reality compete against each other, they demand to be contemplated as part and parcel of a shared context, and as subjects with distinct ways of comprehending facts that had, up till now, never been presented in such spaces.

—Moacir dos Anjos1

View of Imagined Communities, the 21st Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil , 2019. Photo: Everton Ballardin.

Videobrasil was created in 1983 to support and promote the then-fledgling field of Brazilian video production. In a little over thirty years, it has become a benchmark for contemporary artistic production in the geopolitical South. Videobrasil has evolved alongside the video medium, which has become a prevalent tool for visual and political expression. Significantly, Videobrasil has consistently identified and fostered artistic practices from regions with similar persistent challenges rooted in histories of dependence and subordination, which usher in new forms of agency in the face of hegemony, unmasking the power relations that structure our customary ways of understanding the world. These practices owe much to video, an accessible audiovisual medium that combines a documentary quality with a leaning towards experimentation. Videobrasil bears witness to the development of a perspective that reflects its own contexts, needs, and realities while putting identity and minority issues at the centre; it amplifies the vital discourses that confront and destabilise the well-charted, and long-established avenues of art.

Today, Videobrasil is known for both its programmes and its collection, which both owe their existence to a local video festival in São Paulo. Since 1983, the festival has constantly been reinventing itself—in name, frequency, and scale—to keep pace with the widening scope of its mission, and has given rise to a wealth of new projects. At the time of the first Videobrasil festival, Brazil was struggling to overcome twenty years of dictatorship and reconstitute itself as a democracy. The state’s monopoly on television broadcast licences, which played a crucial role in the consolidation of the military regime’s jingoistic political project, had a powerful impact on the post-dictatorship generation’s collective imaginary. Thus, they worked to “invade television,” to show the social realities censored by the regime, to communicate new points of view, and to experiment with audiovisual languages. Their exploration of the political and expressive potential of video was also fuelled by the advent of home-video formats and portable semi-professional equipment, allowing for affordable independent audiovisual production outside the tightly controlled domain of broadcast television and the prohibitively expensive realm of cinematic production.

Attracting an unexpected (and ever-increasing) number of submissions, the early editions of the Videobrasil festival were both a showcase and a catalyst for an openly political art movement aiming to breathe new life into audiovisual language. Though Brazilian television partially absorbed some of these experiments in the favourable context of the post-dictatorship redemocratisation in the early 1980s, local artists and producers nevertheless found themselves at a creative impasse. Videobrasil’s move towards internationalisation was thus conceived as a way to revitalise local production, to provide new references and productive confrontations, to expand the organisation’s network of contacts, and to promote dialogue and exchange. At the same time, the competitive format of the festival’s main section risked replicating existing disparities, pitting established video art practices against emergent approaches and recent productions.

Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, Abdoulaye Konaté: Colours and Compositions, 2017. Video, 29:17 minutes, Videobrasil Authors Collection.

Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, Abdoulaye Konaté: Colours and Compositions, 2017. Video, 29:17 minutes, Videobrasil Authors Collection.

These considerations led us to design and achieve a very specific form of internationalisation. Videobrasil’s eighth edition, in 1990, was developed around an open call for artists from regions of the world shaped by histories of violence, conflict, slavery, colonialism, and other forms of political and cultural subjugation similar to those of Brazil. These artists’ works, like ours, were produced outside the dominant contemporary art and video circuits. Geopolitically inflected, this new and broader scope first encompassed South America, Australia, Africa, and Southeast Asia, and eventually came to include the Caribbean, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East, establishing new relationships with these regions. In addition to revitalising local audiovisual production, Videobrasil was determined to provide visibility and a platform for dialogue and exchange for artists who were deprived of institutional, critical, and commercial acceptance because of the lack of access to established international art circuits.

Our assertion of this expanded and shared territory, and of the strategic need to foster, follow, and disseminate its artistic production found immediate resonance. By shifting our focus to the creation of an ecosystem conducive to exchange and partnership with artists, curators, and institutions in the South, Videobrasil opened itself up to a wider field of research and activity. This expansion in turn accelerated our transformation, which led us to redefine, restructure, and reposition Videobrasil as a hub for curatorial research and a platform for dissemination. In 1991, the Videobrasil Cultural Association was founded, translating our strategic commitment to the geopolitical South into new initiatives and supporting further institutional and programme expansion by establishing important partnerships.

In addition to its annual festival, Videobrasil maintains an important online presence with projects such as FF Dossier, a repository of artists’ portfolios, and produces several audiovisual programmes, including the Videobrasil Authors Collection, a series of authorial documentaries focusing mainly on influential artists from the geopolitical South. We also have a robust print and electronic publishing arm, continually producing catalogues of our exhibitions, as well as Cadernos Sesc_Videobrasil, our annual contemporary art magazine. More importantly, Videobrasil invests in activating the significant collection we have built over the years, by researching, presenting, and sharing the award-winning artworks from our festivals, as well as other selected works and related audiovisual documents. Thus, Videobrasil is now both a touchstone of video production in the geopolitical South and a critical, multifaceted platform charting and promoting a diversified and equitable representation of contemporary artistic output.

Elvira Dyangani Ose, Theo Eshetu, and Teté Martinho in conversation about the 10th issue of Caderno magazine entitledUsos da memoria, 2014.

Elvira Dyangani Ose, Theo Eshetu, and Teté Martinho in conversation about the 10th issue of Caderno magazine entitledUsos da memoria, 2014.

IN TRANSIT

The annual Videobrasil festival—the origin of this multifaceted institution, and still its nexus—has continually reinvented its format over the decades, adapting to an increasingly complex field of artistic production. However, we have maintained our open call as a way to provide equal opportunities and working conditions for artists, experiments, and research that are excluded from dominant art circuits. In parallel, we have increased our research and outreach efforts, especially in regions that tend to receive less attention. Our focus on our chosen geopolitical field has led us to respond to its changing needs and opportunities by adjusting our general course, and to pause, stop, or change direction when necessary. In the first decade of this century, we noticed significant thematic directions that resonate with artists of the South—such as the flows and exchanges between different artistic languages and the notion of dislocation/translocation—on which we began to focus our curatorial framework.

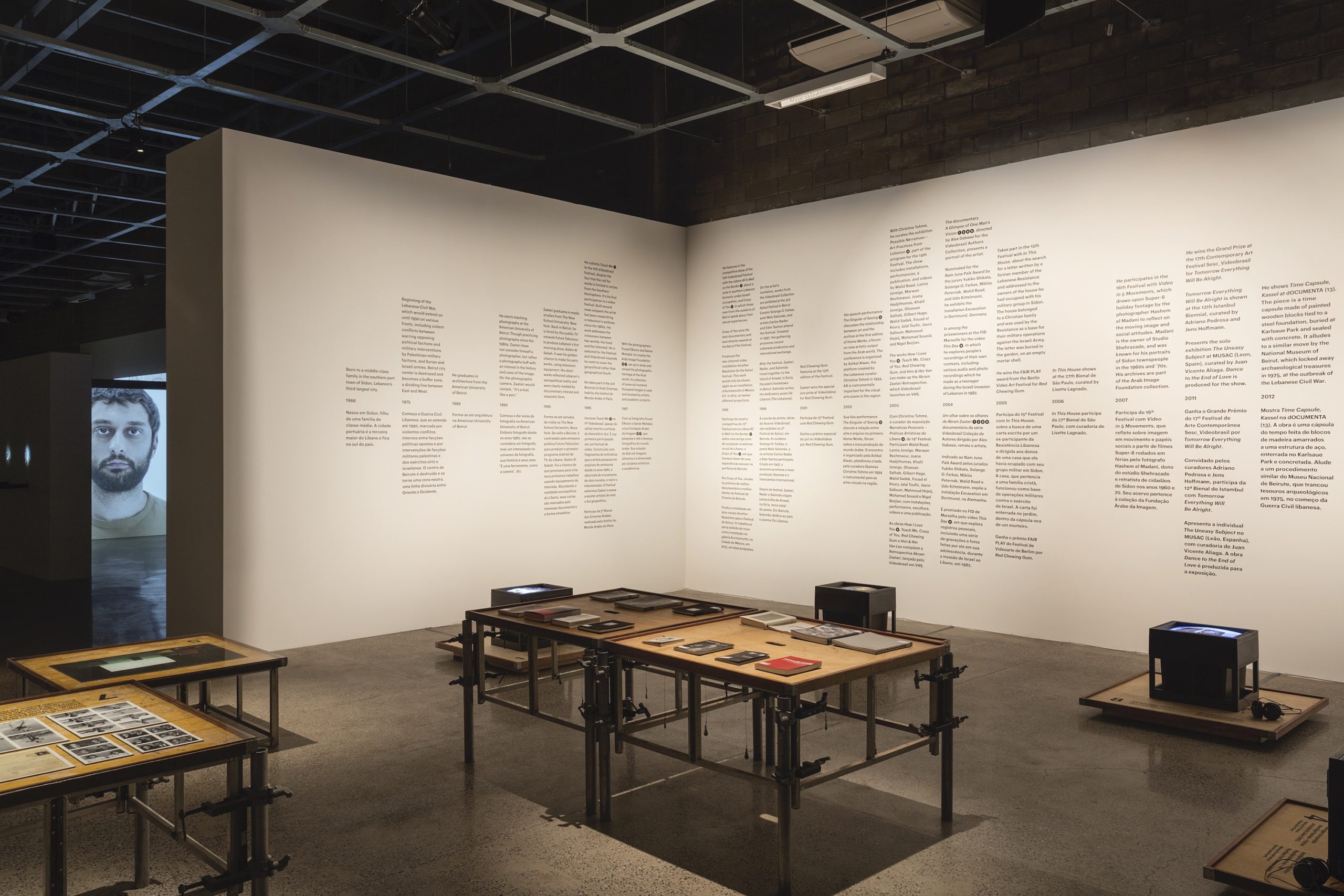

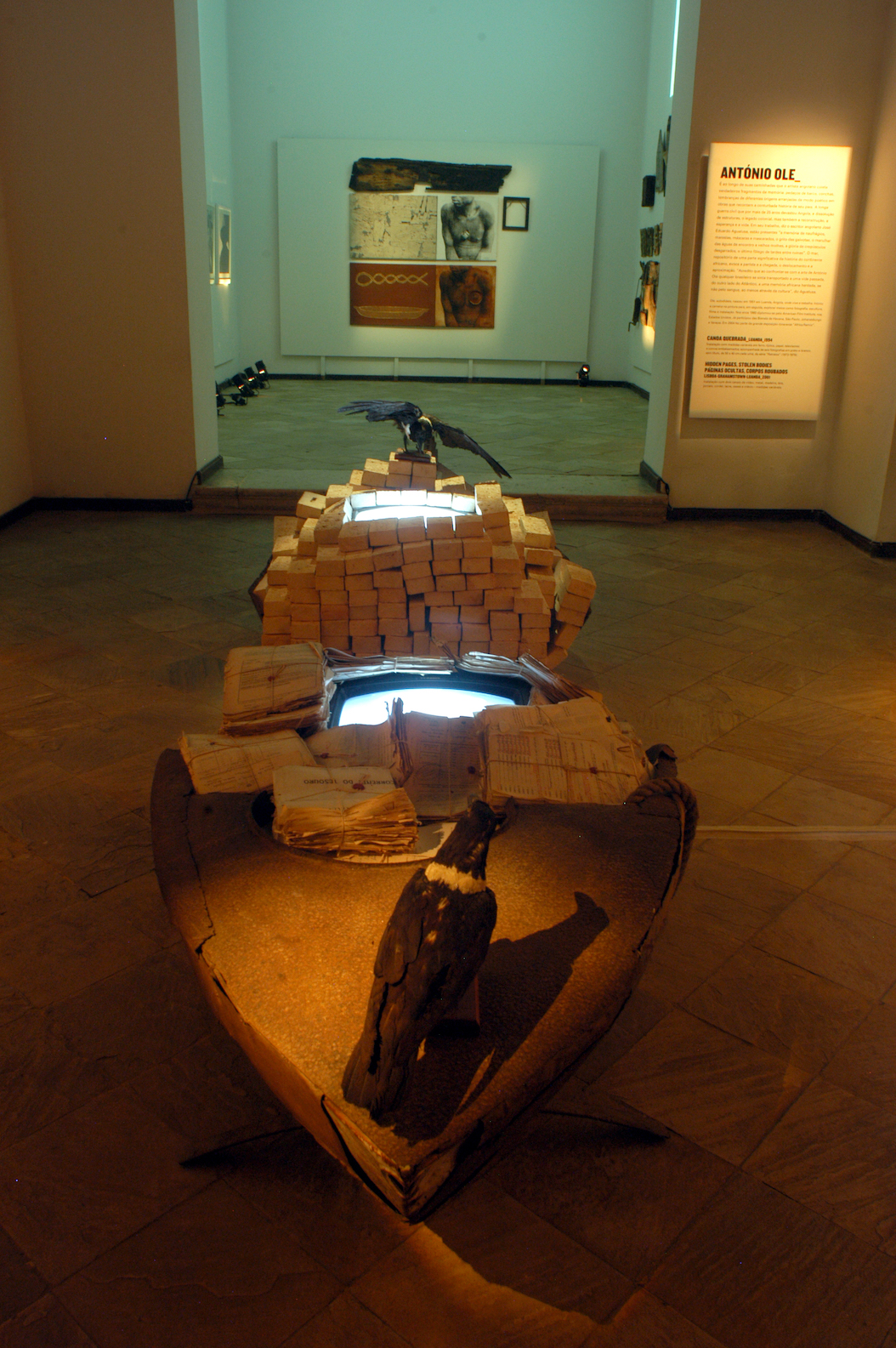

In 2003, Possible Narratives – Artistic Practices of Lebanon was the first exhibition included in the Festival to include works straddling a wide range of artistic languages, bringing together photography, performances, publications, and lectures, in addition to video installations and single-channel videos. Curated by Christine Thomé and Akram Zaatari and featuring works by Joana Hadjithomas, Khalil Joreige, Ghassan Salhab, Gilbert Hage, Lamia Joreige, Marwan Rechmaoui, Walid Sadek, Jalal Toufic, and Walid Raad, the exhibition called attention to conceptual, political, and interdisciplinary production. In fact, Zaatari can be credited with building a bridge to the Middle East: in 1997, he submitted his first video, Teach Me, to our open call, drawing our attention to artistic production that resonated with the geopolitical South by critically exploring a history steeped in military and territorial conflicts. In 2016, Galpão Videobrasil (Galpão VB), the space in which we operated from 2016 to 2019, presented Tomorrow Everything Will Be Alright, Zaatari’s first solo exhibition in Brazil. Possible Narratives – Artistic Practices of Lebanon heralded another important change, which solidified nearly a decade later, in 2011: the opening of Videobrasil to all forms of artistic expression, in recognition of the fact that activist art, concepts, and ideas transcend the media through which they are conveyed.

Throughout the 2000s, as we became an interdisciplinary institution, changes in the international art world itself enabled Videobrasil to develop an initiative to offer artists the transformative opportunity to acquire new skills, discover other modes of artistic production, and develop professional networks by living and working in a different artistic and cultural milieu. In fact, this had long been one of Videobrasil’s goals. In the 1980s, before artistic residencies established themselves as the dominant vector of artist mobility and artworld expansion that they are today (or were, pre-Covid), Videobrasil created its first residency prizes. At the beginning of the 1990s, we experimented by pioneering partnerships—with CICV (Centre international de création video) in France, for instance—that allowed us to offer residencies through juried competitions. At first, these were intermittent and tentative experiments, but in the 2000s Videobrasil started offering residency prizes on a regular basis, in partnership with Brazilian and international institutions. In response to the changing needs of artists and their shifting methodologies, these residencies offered work and research support as well as living experiences abroad.

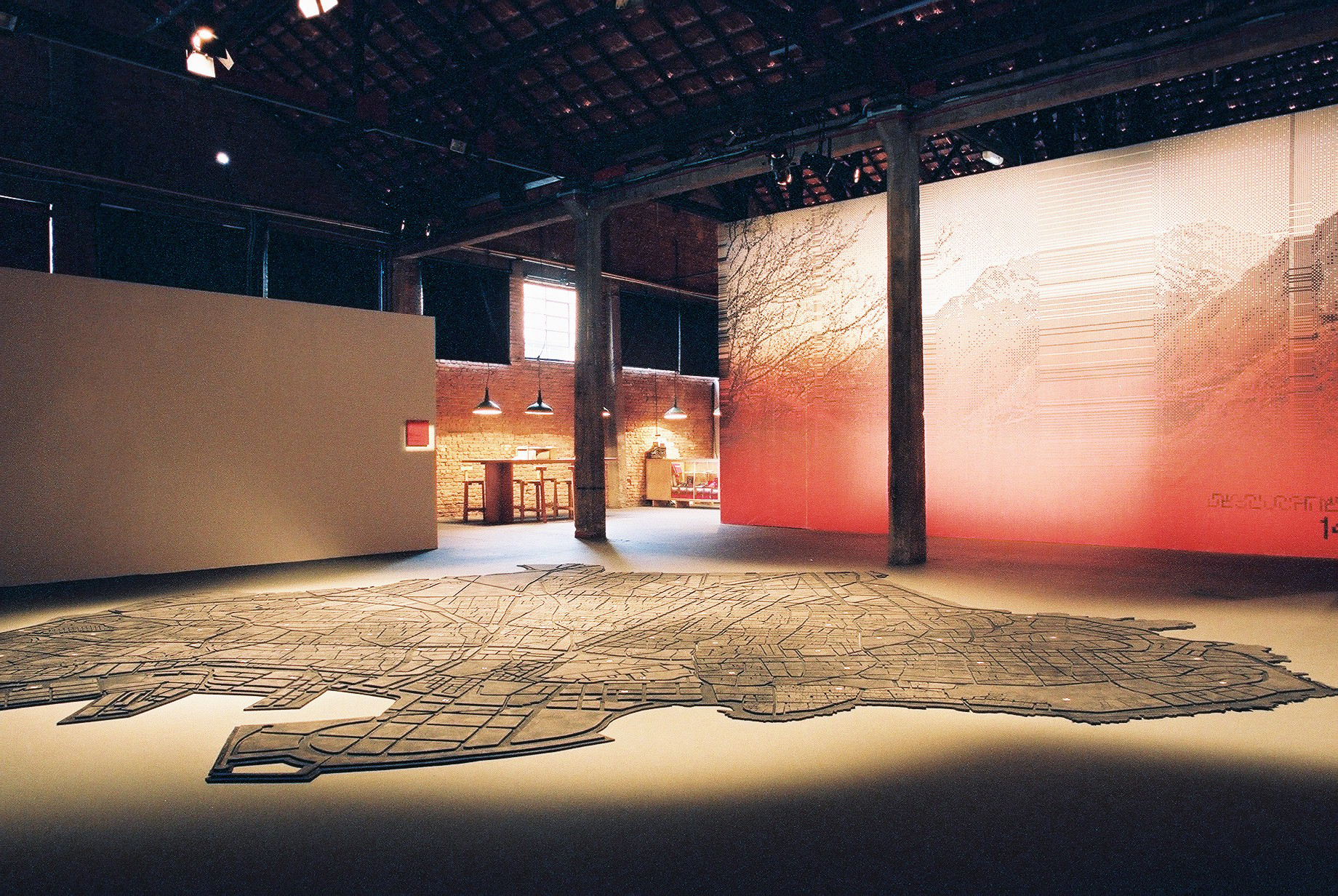

Akram Zaatari, Beirut Exploded Views, 2014. Presented in the exhibition Tomorrow Everything will be Alright, 2016. Photo: Everton Ballardin.

The post-9/11 world—a strange form of together-apart, a shrinking of distances brought about by cheap travel and fast internet, paralleled by the rise of isolationalist, if not tribal, conservative forces—saw the widespread multiplication of artistic residency programmes. Many residency organisations understand the support of ongoing artistic development to include that of the local community. As a result, these programmes often design settings and situations favourable to reciprocal exchange, impacting resident artists as well as host communities. Partnerships with organisations on all five continents now enable Videobrasil to offer a diversity of residencies, whose focuses range from studio to site-responsive and participatory practices.

This network of residency partners has taken on new strategic significance for Videobrasil. In 2013, we published the book entitled In Residency—Routes for Artistic Research in 30 Years of Videobrasil, bringing together testimonies by some of the nearly forty artists who participated in Videobrasil’s programmes between 1990 and 2013. By connecting visual arts institutions all over the world, this collaborative network helps bolster Videobrasil’s presence in countries with precarious or non-existent art infrastructure, whose contemporary art activities are harder to access. Our efforts have been rewarded by a surge in the number of festival applications from African countries such as Senegal, Cameroon, and South Africa, where museums, contemporary art centres, and universities have increased the number of residencies in an attempt both to retain artists and to enliven and diversify local art scenes.

LIVING MEMORY

As Videobrasil evolved, the collection became central to our research and programmes. Comprising roughly three thousand works, the collection preserves the memory of recent audiovisual production in the global South. In addition to the works that have been featured in our exhibitions, it also includes collections donated by artists such as Rafael França and Eder Santos, our own productions such the Videobrasil Authors Collection documentaries, recordings of performances, interviews, forums, and debates related to our exhibitions, and international video artworks of historical importance.

The creation of the collection was initially motivated by the urgent need to preserve fragile electronic media artworks. The safeguarding of such a significant collection spanning four decades is an enormous responsibility in a country that suffers from a chronic lack of consistent cultural policies, especially regarding the preservation of important cultural artefacts. Working on the collection, we realised that its stewardship required more than just preservation and a simple archival-descriptive approach to the works (both of which already present vast technical challenges in themselves). We began to address this issue with VB Platform, which publishes artists’ reflections on their own work, and FF>>Dossier, dedicated to annotated biographies and critical essays on artists represented in the collection. Keeping a collection of this scale alive and relevant demands a curatorially inflected practice and at the same time makes such an approach possible. We take a curatorial approach to the collection and the issues that stem from it, which is to say, we explore it from the standpoint of the present. This allows us to recover and reclaim works, to create cross-sectional studies, and to instigate research and exchanges across times and places, which is for us a contemporary means of preserving the history of video.

Akram Zaatari, Beirut Exploded Views, 2014. Presented in the exhibition Tomorrow Everything will be Alright, 2016. Photo: Everton Ballardin.

Bakary Diallo, Renée Akitelek Mboya comenta “Tomo”, (2012), 2020. Video.

Bakary Diallo, Renée Akitelek Mboya comenta “Tomo”, (2012), 2020. Video.

Since the 1980s, many curators have researched the collection to develop video art festivals and exhibitions at institutions in Brazil and abroad. However, it is during the Galpão VB years that the activation of the collection gained potency and prominence, giving it a more definite shape. Our Galpão VB facility combined our headquarters with an exhibition space, allowing us to approach the collection as both an artistic and a memory preservation project—that is, as the source of a historical, curatorial, and poetic discourse. In turn, our new programming approach has gradually revealed the intrinsically dissonant nature of audiovisual production in the geopolitical South. Shaped by emergent political voices broaching long-standing (yet no less urgent) issues such as social inequality, racism, sexism, and the genocide of Indigenous peoples, audiovisual production from the global South intersects with the intense process of revision and correction carried out in the arts, humanities, and social sciences through postcolonial approaches.

The exhibition Unerasable Memories, organised by Spanish curator Agustín Pérez Rubio in 2014, drew on his extensive knowledge of the collection. It exemplified the potential in rediscovering historical productions and combining them creatively, thereby renewing their relevance to the present. Bringing together works created at different times and places, the exhibition addressed traumas that share a history of erasure, including the European conquest of the Americas and the genocide of Indigenous peoples, slavery and twentieth-century agrarian struggles, and the military coup in Chile and the Tiananmen Square massacre. The exhibition featured works of artists from different generations, such as Aurélio Michiles, Jonathas de Andrade, and Rosângela Rennó from Brazil, and León Ferrari and Sebastian Diaz-Morales from Argentina, inviting one to consider, how the history of these conflicts is viewed from the present, where everything seems distant and past, but issues of race, sex, gender, slavery, borders, and wars continue to occur. […] Through their works, these artists put their finger on such issues and call on us to join in the response, to fight for or reject these facts, or to give us back the memory of them.2

The idea of recovering and reclaiming stories that have been written out of dominant accounts by the so-called winners—to create counternarratives that defy the official histories—traverses most of the works found in Videobrasil’s collection and exhibitions. Unerasable Memories showed how this imperative could be expressed in highly diverse registers, from the documentary to experimental work and installations.

Geopoetics, an exhibition of works by the Black British visual artist Isaac Julien that I organised in 2012, showcased the ways in which postcolonial thought, aware of the implications of multiculturalism and sensitive to gender issues, plays a fundamental role in the creation of a new and sophisticated form of filmmaking that expands beyond the screen and into its surroundings. In this exhibition, a symphony of visual and sonic fragments wove together narratives that drew on a tragedy involving Chinese workers in England, contrasted the arid interior of Burkina Faso, the world’s poorest country, with what Julien terms the “sublime white” landscape of the North Pole, and revisited the works of the Martinican writer Frantz Fanon.

Forever in need of being addressed, the questions of race and raciality—the deadly legacy of slavery and colonialism—feature prominently in Julien’s work, as well as in those of countless other award-winning and guest artists who are represented in Videobrasil’s collection and feature in its curated exhibitions, from the Pan-African Exhibition of Contemporary Art in Salvador in the state of Bahia in 2005, to Crossings, created especially for the 12th Biennale de Dakar, The City in the Blue Daylight, in 2016. The former featured works by artists and thinkers associated with the Black diaspora in Salvador, one of the main ports of the slave trade in colonial and imperial Brazil; in the latter, artworks by Brazilian artists of African ancestry exemplified the many possible ways to address the legacies of racism. Paulo Nazareth’s performative video L’arbre d’oublier was filmed in Ouidah, Benin, once home to one of Africa’s largest slave trafficking ports, where many ships left for Brazil in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Its title is taken from the “Tree of Oblivion,” which men were forced to circle seven times before boarding slave ships, in a ritual that was meant to erase the memory of their families, their country, and their past. In a poetic attempt at rewinding history, Nazareth circles the tree 437 times, backwards.

Detail of the exhibition Now We Are All Black, 2017. Photo: Pedro Napolitano Prata.

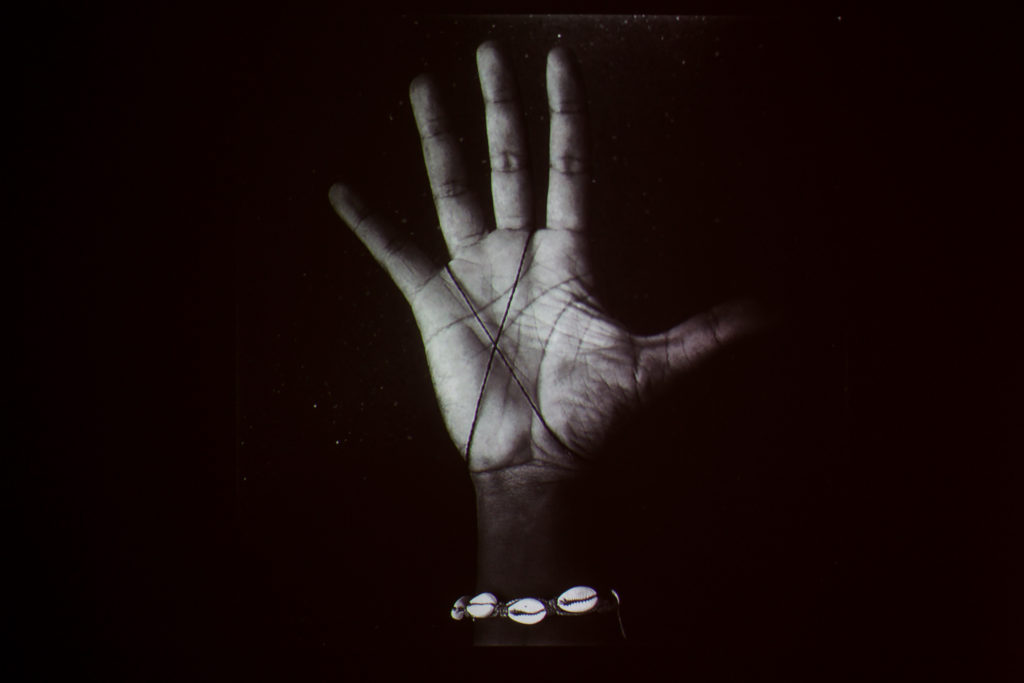

Crossings also featured works by Daniel Lima, whose artistic production enlists public and urban spaces for simultaneously aesthetic and political gestures. Lima has participated in Videobrasil several times, including a performance in 2005 alongside Frente 3 de Fevereiro, an anti-racist research and direct-action collective founded in 2004 following the murder of the young Black student Flavio Sant’Anna by São Paulo’s military police. Using Videobrasil’s collection, he organised the exhibition Now Are We All Black? in 2017, which challenged deluded assertions of racial equality in Brazil. The works he assembled reaffirm the struggle of Black artists to deconstruct the “triple trauma of colonisation (extermination of indigenous populations, slavery, and religious persecution) through the micro-political power of art.”3 With the works of emerging artists such as Moisés Patrício—whose Aceita? series, originally broadcast on social media, questioned the systemic racism that still often relegates the Black population to low-paying day labour—Lima juxtaposed and contrasted pieces by well-known artists such as Rosana Paulino, whose work employs diverse languages and a poignant delicacy to expose extreme situations, such as the normalisation of violence against women, which is even more extreme for Black women. The poetic and political potency of Paulino’s narrative, and the way she addresses issues of memory, ancestry, and Black identity, were also featured in 2019 in the 21st Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil, which commissioned her first ever video work.

Detail of the exhibition Now We Are All Black, 2017. Photo: Pedro Napolitano Prata.

MINORITISED COMMUNITIES

The eleventh issue of Cadernos Sesc_Videobrasil, fittingly titled An Alliance of Vulnerable Bodies: Feminisms, Queer Activism and Visual Culture and published in 2015, shed light on sexual dissidents who resist submission to patriarchal heteronormativity. Edited by the Peruvian curator Miguel Angel López, the magazine explored “how feminisms, queer activisms, sexual disobedience and other coalitions of desires of non-normative bodies respond to and redefine the logic of exclusion and erasure that organises social space.”4 With essays by thinkers such as the philosopher Paul B. Preciado and the art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson, as well as activist collectives like Serigrafistas Queer from Argentina, the magazine proposes “a mestiza perspective with regard to the sexual-dissident struggles: transfronteiço [transborder] and promiscuous positionings invoked from the South to confront the epistemologies of the North, its modern/colonial systems of gender and sexuality and the hegemony of the white Western subject.”5

Investigations of feminism, gender roles, patriarchy, and sexual normativity, seen from the mestiza and doubly dissident perspective of the geopolitical South, recur throughout the history of Videobrasil. In 2017, an exhibition titled Nada levarei quando morrer, aqueles que me devem cobrarei no inferno (I won’t take anything with me when I’m dead, those who owe me will be held accountable in hell), held at Galpão VB, featured works that explored resistance in cultural practices and forms of living that insistently assert their strength, and above all their particularities. In the 2015 Cais do corpo series, presented in an exhibition on view during the “revitalisation” of the port zone in Rio de Janeiro for the 2016 Olympics, Bahian artist Virgínia de Medeiros recounts the decline of the red-light district that had existed in the area in the 1930s. Framing the performativity of sex workers’ bodies as a social and political practice, the work tackles the version of modernisation defended by an urbanism that ignores human activity and exempts itself from the imperative of designing in a way that fosters social inclusion. In the 21st Contemporary Art Biennial Sesc_Videobrasil, Mexican artist Teresa Margolles invited Brazilian transvestites and transsexuals to embroider their life stories onto a piece of fabric. The resulting work, a textile object steeped in meaning, poignantly reveals the community-affirming power of manual, collective, and feminine labour.

Reasserting the achievements of silenced and minoritised groups, such as LGBTQs, Blacks, Indigenous peoples, and women, the 21st Biennial responded to renewed challenges to fight inequality and injustice, enlisting once again the utopian desire to refashion the world around communities of kinship and care. By adopting the Biennial format, Videobrasil emphasised its alignment with an emergent model of international biennials, which, unlike other exhibition formats that deploy extravagance and the superlative, subjecting themselves to the vicissitudes of the art market, aspires to reassert the relevance of art in its critical, restless, and world-creating dimension, especially in the context of economic and health crises and political regression.

Women played a leading role in all areas of work and decision-making in the 21st Biennial (which boasted, for instance, an all-female jury). The Biennial was also marked by the considerable presence of Indigenous contemporary artists from Brazil and beyond. An ever-present subject since Videobrasil’s early editions, indigeneity has claimed an even greater role over the past few years in projects that draw on Videobrasil’s collection. Filmmaker Andrea Tonnaci (1944–2016), a forerunner of Brazilian Indigenous audiovisual militancy, was honoured by the Biennial with a commission that allowed him to complete a project he had begun in 1977, aimed at mapping the violence committed against Indigenous communities in Latin America.

Ayrson Heráclito: Sacudimentos, 2020. Video.

Ayrson Heráclito: Sacudimentos, 2020. Video.

Originally planned for 2021, the 22nd Biennial is subject to the vagaries of our current moment, when the pandemic is amplified by Brazil’s lethal misgovernment. While people revisit their everyday practices and institutions renegotiate the publicness of art and cultural productions, the Videobrasil Online project draws on both the unique characteristics of our collection and our vast experience in curatorial exchange to experiment with online viewing formats and to further the integration of our content in exhibitions and special programmes. Such activities will allow us to keep moving towards the democratisation of artistic production in the geopolitical South through the curatorial deployment of the Videobrasil collection in diverse exhibition programmes, as we stay abreast of the developments and urgent needs of each new moment. Though our present climate may not lend itself to the expansion of partnerships and cultural projects that promote diversity, liberty, communal thought, and awareness-raising, we are nonetheless more certain than ever of the importance of keeping alive one of the most significant video collections of the world’s geopolitical South.

NOTES

1 Moacir dos Anjos, “The Time of the South,” in Videobrasil: Três décadas de vídeo, arte, encontros e transformações, ed. Solange Farkas and Teté Martinho (São Paulo: Edições Sesc SP / Associação Cultural Videobrasil, 2015), 317.

2 Agustín Pérez Rubio, “Facing Mirrors: Projecting Memories Against Historical Amnesia,” in Memórias inapagáveis – Um olhar histórico no Acervo Videobrasil / Unerasable Memories – A Historic Look at the Videobrasil Collection, ed. Agustín Pérez Rubio (São Paulo: Edições Sesc SP / Associação Cultural Videobrasil, 2014), 29.

3 Daniel Lima, “Now Are We All Black?” Exhibition text, Videobrasil.org, http://site.videobrasil.org.br/en/exposicoes/galpaovb/agorasomostodxsnegrxs.

4 Miguel Angel López, “Alliances of Vulnerable Bodies,” in Alianças de corpos vulneráveis – feminismos, ativismo bicha e cultura visual / Alliances of Vulnerable Bodies – Feminisms, Queer Activism, and Visual Culture, ed. Miguel A. López (São Paulo: Edições Sesc SP / Associação Cultural Videobrasil, 2016), 9.

5 López, 9.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Solange O. Farkas has been professionally active in the cultural field for four decades. Farkas is the founder and director of Associação Cultural Videobrasil, and has been the artistic director of the Sesc_Videobrasil festival and biennial since its first edition in 1983.

She has been Chief Curator of the Museum of Modern Art of Bahia (2007–2010) and a guest curator for several festivals and biennials, including FUSO–Mostra Anual de Videoarte, Lisbon (2011, 2013 and 2017), Dak’Art 2016–Biennale de Dakar (2016), the 6th Jakarta International Video Festival (2013), Sharjah Biennial 10 (2011), the 16th Cerveira International Art Biennial, Cerveira, Portugal (2011) and the 5th Video Zone–International Video Art Biennial, Tel Aviv (2010).

In recent years, she has been a member of the prize jury of the Sharjah Biennial 14 (2019), the Prince Claus Fund Award prize committee (2017–2018), the jury of the 10ème Rencontres de Bamako, Biennale africaine de la photographie [African Photography Biennial] (2015), the curators’ selection committee for the 11th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art (2020), and has helped organise the Anthropocene Project exhibition at the Ilmin Museum of Art, Seoul, South Korea (2019).

She is a member of the jury of the Eye Art & Film Prize, Amsterdam, and is on the consulting board of Pivô in São Paulo. In 2017, she received the Montblanc Arts Patronage Award.