Zineb Sedira

There Is No Real Solidarity without Physicality

- 05.02.2021

Zineb Sedira, Scene 3: Way of Life, 2019. Video installation with various 1960s objects, filmed interview (Nadira, 2019. Video, approx. 40 minutes), and playlist. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in 4 scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

Last summer, we spoke with Zineb Sedira, an artist who has participated in biennials around the world since 2001 and has been selected to represent France at the Venice Biennale in 2022.

This conversation is part of an ongoing series of in-depth exchanges with artists about the impact of biennials on contemporary artistic practice. Though broad statements abound about the centrality of artists to biennials, artists are rarely asked what biennials mean to them. This series aims to listen intently to a diverse group of artists with vastly different biennial experiences in order to better grasp our contemporary reality as we imagine together the possible futures of biennials.

Zineb Sedira, Scene 3: Way of Life, 2019. Video installation with various 1960s objects, filmed interview (Nadira, 2019. Video, approx. 40 minutes), and playlist. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in 4 scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

PART I: July 3, 2020

°°°

SYLVIE FORTIN Your work has been presented in numerous biennials, and so in many different locations and political contexts. How have biennials supported your practice? Have they supported the development of specific directions or facilitated certain inquiries?

ZINEB SEDIRA When I think about biennials, I immediately think of Venice. Authentic/Ex-centric: Africa in and out of Africa, curated by Salah Hassan and Olu Oguibe in 2001, was my first showing at the Venice Biennale. It was also the first African Pavilion, which created a lot of hype.

At the time there was a polemic around the definition of Africa, which often led to North Africa being excluded or marginalised. In this show, the curators made the case for an inclusive global Africa, encompassing North Africa and the diasporas. It was very significant for me to be included in this context, as I was tired of hearing that I was too white to be African. Geopolitical experience rather than skin colour was the premise for the show.

I am very fond of that show; it significantly increased the visibility of my work and had a big impact on my career. Over the next decade, I was invited to participate in quite a few biennials, triennials, and quadrennials: a sort of biennial circuit.

ANNE BARLOW From your perspective as an artist, did it matter that this exhibition was part of a biennial rather than being presented by a museum or some other art institution?

ZINEB SEDIRA Biennials offer more visibility, since they attract many more visitors from all over the world. As such, biennials are more international viewing spaces. Although institutions like Tate Modern, the Centre Pompidou, and MoMA claim to welcome many international visitors, their power of attraction is nowhere near that of biennials. After all, one of the main goals of biennials is to gather a truly international audience. Few people travel to New York, London, or Paris expressly to see a museum show; many more go to visit a biennial. A biennial is also more than an exhibition; it offers a broader array of engagement. It is a gathering, an event offering encounters with artists and their works, discussions, and networking amongst professionals. Some of these events offer direct engagement with local people. This is what interests me.

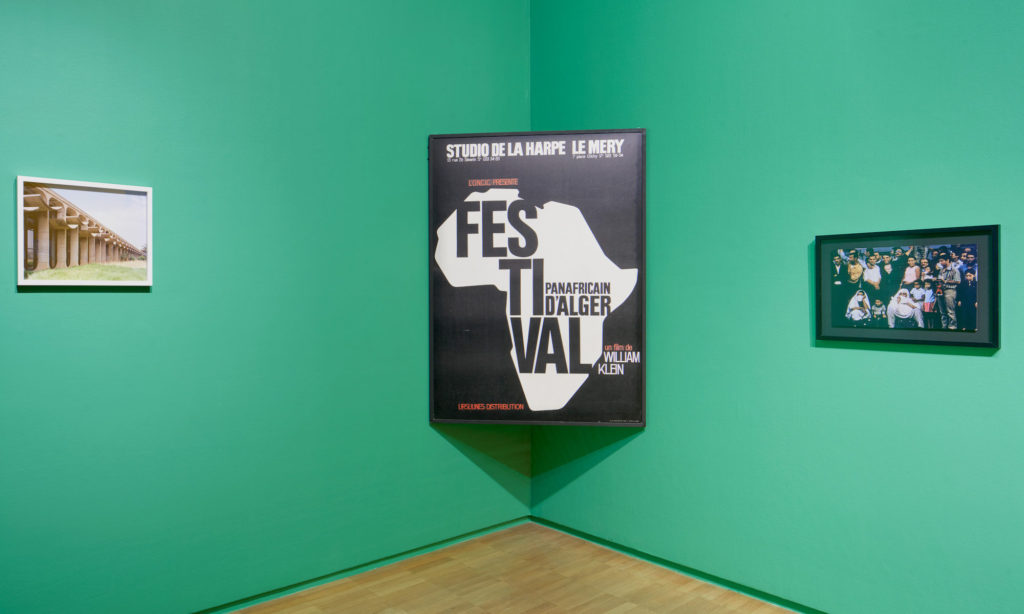

SYLVIE FORTIN The Festival panafricain d’Alger (1969)—an event that is biennial-like in scale—was centrally featured in your recent solo show at the Jeu de Paume in Paris. Can you speak about this project?

View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019 at Jeu de Paume, Paris. © Jeu de Paume, Paris. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019 at Jeu de Paume, Paris. © Jeu de Paume, Paris. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

ZINEB SEDIRA There is a very interesting relationship between biennials and the Festival panafricain d’Alger, which was a cultural festival. The Festival included music, cinema, theatre, as well as visual art; it was more culturally comprehensive than contemporary art biennials.

In addition, the program of the Festival d’Alger had a strong political bent. Culture was seen as a weapon to fight imperialism; a rediscovery of Algeria’s and Africa’s rich and diverse cultures was deemed necessary to counteract years of colonisation. Bringing together many liberation movements from the “Global South,” the festival also aimed to usher in the emergence of a post-imperial world.

Today’s contemporary art biennials are often detached from any tangible politics or social issues, be they local, national, or global. They approach “politics” as a theme around which to gather the works of relevant artists. While curators may include projects that might be deemed political, the biennial itself is rarely a political act.

Taking place right after 1968, a watershed for anti-war, anti-colonial, anti-imperialist, and feminist militancy, the Festival panafricain d’Alger had deep international resonance. Algeria had gained independence from France in 1962 and became an anti-colonial paradigm. It also paved the way for other anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movements around the globe, including in Latin America, the Canary Islands, Ireland, Vietnam, and Palestine, as well as the anti-fascist movements in Spain and Portugal. In fact, I titled one of my works For a Brief Moment the World Was on Fire…, pointing to the heady emergence in the 1960s of militant and countercultural movements around the world.

The Festival panafricain d’Alger was remarkable because it allowed Algerians to discover their own Africanness, while also discovering the richness of Algeria’s own cultural diversity. Since the dialogue was no longer focused on Europe, other conversations could emerge. Significantly, the Festival also extended hospitality to anticolonial solidarity movements around the world. It was an important moment before Algeria tangled itself up in pan-Arabism and pan-Africanism.

A crucial difference between biennials and the Festival panafricain is, of course, context. The invitation to Algiers in 1969, at this specific post-independence moment, really meant something. So did the effervescent connectedness of international movements that could be experienced there. The art, the plays, the films, and the concerts that were created reflected that reality, which is very different from ours now.

Zineb Sedira, Scene 2: For a Brief Moment the World Was on Fire…, 2019. Photomontages with various 1960s objects and books, DVD, and 1 film canister; Scene 2: We Have Come Back, 2019. Collected 7″ & 12” vinyl records of militant music from the 1960s. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in four scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019, at Jeu de Paume, Paris. Commissioned by Jeu de Paume, Paris; IVAM, Valencia, Spain; Gulbenkian, Lisbon; Bildmuseet, Umeå, Sweden. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

Zineb Sedira, Scene 2: For a Brief Moment the World Was on Fire…, 2019. Photomontages with various 1960s objects and books, DVD, and 1 film canister; Scene 2: We Have Come Back, 2019. Collected 7″ & 12” vinyl records of militant music from the 1960s. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in four scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019, at Jeu de Paume, Paris. Commissioned by Jeu de Paume, Paris; IVAM, Valencia, Spain; Gulbenkian, Lisbon; Bildmuseet, Umeå, Sweden. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

ANNE BARLOW I’m interested in your comment that biennials today are devoid of any real politics, in the sense that they may include political subject matter but not be political in and of themselves. Do you feel that any recent biennials have been able to break out of that tendency, and if so in what ways?

Alongside that question, the pandemic has only highlighted the pervasiveness of social inequality and the need for a seismic shift that will challenge dominant frameworks, hierarchies, and histories (a process likely to reveal further inequalities). This affects art and culture. In your view, how does the pandemic call on them to play a role in terms of driving change?

ZINEB SEDIRA One of the mantras of the Festival panafricain and its symposium was “Culture as a political weapon in the fight against prejudice and injustice.” I like to think that we are going to learn a lot from the pandemic. I am also very mindful of environmental issues, of what we are doing to the world. During the COVID-19 crisis, we have all witnessed the disproportionate loss of lives and economic impact, the ravages of ongoing race and class inequalities.

Together, the killing of George Floyd in the US and the pandemic created conditions favourable to the awakening of political consciousness and a moment of global solidarity. Most people were at home, confronting the same fears and focused on the media on their screens. In that moment, a global consciousness emerged, a kind of countercultural moment with #BlackLivesMatter and other sociopolitical movements such as Extinction Rebellion. But of course the big question is, will this movement be sustainable?

SYLVIE FORTIN The environment, justice, and solidarity are crucial questions for the biennial field. COVID-19 has sharpened the challenge: how can we proliferate international solidarities that are environmentally responsible, more-than-humanly aware, and responsive to crises? What models and collaborations will we put in place to sustain mobility, exchange, and solidarity?

Your exhibition at the Jeu de Paume offers food for thought because you mobilize 1969 in many ways: as a vector for research, as the focus of a collection, and as a space for living. The artistic gesture is twofold: first, the development of your own museum or archive in/as your living space; second, its transplantation into public space by way of a diorama including your own furniture. Can you speak about these strategies of presentation?

Zineb Sedira, Scene 3: Way of Life, 2019. Video installation with various 1960s objects, filmed interview (Nadira, 2019. Video, approx. 40 minutes), and playlist. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in 4 scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

Zineb Sedira, Scene 3: Way of Life, 2019. Video installation with various 1960s objects, filmed interview (Nadira, 2019. Video, approx. 40 minutes), and playlist. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in 4 scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

ZINEB SEDIRA I was born in the 1960s. I work with archives and I collect objects from the 1960s, from many parts of Africa. My living room furniture is from the 1960s. I have many outfits and a collection of vinyl records from this period. I wasn’t thinking about my everyday surroundings when I started working on the 1969 Festival panafricain. But since my work is also autobiographical, it made sense for my living space to become part of my new work. Thus, I decided to include my furniture and objects in the work Way of Life, which is part of a larger installation entitled Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, at the Jeu de Paume. I recreated my living room in a diorama format, akin to a stage design for a play or a film. Exhibiting and sharing this space in an art institution was not only personal but also a political act.

A living room is a convivial space where one usually hosts friends, a space to socialise and entertain. I therefore wanted to invite visitors to sit and spend time in my personal space, to consult my collection of books, archives, objects, and music related to the Festival panafricain. They could also watch an interview with Nadira Laggoune, in which she speaks of her experience as a seventeen-year-old attending the festival in Algiers.

We could say that this living room is like a micro-biennial; a micro-festival with cultural activities and political alliances. For me, it was important to examine how political consciousness was shared around the world in the 1960s, connecting diverse militant groups and fostering solidarity. What happens to culture today as a political weapon to fight injustices and wars? We recently glimpsed an answer to this question during the Black Lives Matter demonstrations. People across the globe rose up and took to the streets to fight the same problem: racial injustice.

SYLVIE FORTIN What do you mean by biennial-like? Is it a temporal dimension? Or is it about a specific mode of interpellation? Or something else?

ZINEB SEDIRA Way of Life invited participation and a sharing of knowledge. Biennials often invite people to come into an exhibition space, a pavilion, or a discursive space to discover art works, to interact with artists, and sometimes to be the artwork. By mobilising the living room—the space where guests are hosted—the installation extended an open-ended invitation to explore the idea of solidarity with Algeria, Africa, and other postcolonialities. I wanted people to participate, enjoy, relax, interact, discover books, music, and DVDs, or watch a movie. In that sense, these actions also connect to the spirit of biennials.

SYLVIE FORTIN Do coming and returning reflect a more casual encounter?

ZINEB SEDIRA I was told that visitors kept coming back to interact with the work. The installation was accessible, and privileged an intimate, palpable, and physical experience. Many people could relate to it, since most of us have a living room we share. It was a very “transparent” and honest work: I opened my private space to others. It was a “courageous” piece and I think the audience liked it for its integrity, vulnerability, and generosity, since they were invited to be part of it, to become it.

SYLVIE FORTIN A different sense of time also reigned in that space. COVID has made us more aware of institutional time: online-ticketed, touch-free, timed entries have rendered it obvious. Way of Life allowed both the existence and the experience of a different temporality within the institution. In Way of Life, we are immersed in the revolutionary 1960s, materialised through books, records, objects, and documents. All of a sudden, we inhabit two spaces and two temporalities. As a visitor, we’re not just retracing history—walking the (time)line through different epochs, as is often the case in museums—we are also simultaneously in a living room, participating actively in the shared experience of different times.

Zineb Sedira, Scene 3: Way of Life, 2019. Video installation with various 1960s objects, filmed interview (Nadira, 2019. Video, approx. 40 minutes), and playlist. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in 4 scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

Zineb Sedira, Scene 3: Way of Life, 2019. Video installation with various 1960s objects, filmed interview (Nadira, 2019. Video, approx. 40 minutes), and playlist. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in 4 scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

ZINEB SEDIRA Biennials, festivals, and museum exhibitions all have to be spaces of knowledge—spaces to share and discuss knowledge. Artists share facts and fictions; they often revisit, transgress, and reappropriate history and conventional archives by conceptualizing them very differently from traditional researchers such as historians, scholars, and academics. Artists have a different approach to archives and documents, and thus to history and memory. And yes, Way of Life speaks both about a specific past and about the present: the life of a contemporary artist living in Brixton (London) with its political, social, and domestic interests and preoccupations.

SYLVIE FORTIN Can you tell us about what you are doing for Venice?

ZINEB SEDIRA I am working again on the idea of solidarity. For Venice, I’m exploring the cultural and political solidarity that was developed between France, Italy, and Algeria from the 1960s to the 1980s, for which cinema became the focus. The Cinémathèque d’Alger was created in 1965, under the guidance of the Cinémathèque française. At the time, the Algerian state was investing heavily in culture, including the Festival panafricain and film production; in the following two decades, Algeria coproduced at least twenty-five films with Italy and France. Initially, militant film-makers were invited to produce films about Algeria’s colonial past or with an anticolonial focus. There are many great examples: the Algerian-Italian co-production The Battle of Algiers, directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, was financed entirely by Algeria; the Algerian-French political thriller Z (1969) directed by Costa-Gavras; the Italian-Franco-Algerian film Le Bal (1983), directed by Ettore Scola, which tells a fifty-year-long story of French war and political struggles by way of a ballroom. This is to name only a few. Many well-known film-makers, especially Italian (communist) directors, sought for political reasons to work with Algeria.

The Battle of Algiers won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1965. This award was a strong political statement, proclaiming Italy’s disagreement with France’s stance on colonialism. Deemed a public affront by France, it created a political incident between the two countries. (In the 1960s, film awards were often political acts.) The movie was banned from television broadcast in France until 2004, and while the film could be screened in cinemas from 1970 onward, fear of attacks from French proponents of colonialism meant that only a few movie houses showed it.

Many communists and leftists in Italy and France were ideologically aligned with the Algerian struggle; this provided fertile ground for militant cinema. It facilitated cultural exchanges that enriched Algeria’s nascent cinematographic production infrastructure.

Cinémathèques in Europe were important spaces of solidarity, since they showed political films otherwise not widely distributed. Since I am French and Algerian, and both the Venice Biennale and the Mostra Venice Film Festival take place in Italy, I decided to create a work about the involvement of these three countries in militant cinema. Much of my research will be around the Cinémathèque française in Paris, the Cinémathèque d’Alger and the three cinémathèques in Italy (Cinecittà in Rome, Cineteca di Bologna, and Cineteca di Torino).

Algeria also had vital alliances with other countries, including Yugoslavia, Palestine, various sub-Saharan states, and Egypt. Youssef Chahine’s three films, as well as works by the Lebanese director Jocelyne Saab, the Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, Souleymane Cissé from Mali, and many others were coproduced by the Algerian state. The ethos of Algerian film production and the Cinémathèque d’Alger was modelled after Cuba’sInstituto Cubano del Arte y la Industria Cinematográficos and its journal Cine Cubano (1960), which defined film as “the most powerful and provocative form of artistic expression, and the most direct and widespread vehicle for education and bringing ideas to the public.” The relationship between Algeria and Cuba was close, forged in the crucible of anti-imperialism and revolution.

That being said, my project will focus primarily on cinema directed by French, Algerian, and Italian directors and their political and cultural engagements.

Zineb Sedira, Scene 3: Way of Life, 2019. Video installation with various 1960s objects, filmed interview (Nadira, 2019. Video, approx. 40 minutes), and playlist. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in 4 scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

Zineb Sedira, Scene 3: Way of Life, 2019. Video installation with various 1960s objects, filmed interview (Nadira, 2019. Video, approx. 40 minutes), and playlist. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in 4 scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

SYLVIE FORTIN What can we learn from such institutional solidarity as we imagine what biennials could become? COVID’s reconfiguration of the world may be as radical as the reworlding that followed decolonisation. Can the experiences of the Festival and the Cinémathèque d’Alger help us design spaces of possibility and protocols of interaction for a different kind of future?

ZINEB SEDIRA It really depends on the country. If Algeria had a biennial, I would want it to be strongly connected with both local people and the “Global South,” as the Festival panafricain was. I would hope that the organisers and directors/curators would be aware of the specificity of the cultural and political context. I would also be vigilant not to turn it into a wonder and a display just for a limited international art world. Biennials should always benefit the local art scene first, before involving the international community. Many biennials start modestly but as they internationalise they lose their initial spirit and their specific national characteristics; they end up adopting the same globally sanctioned formats and structures.

Freedom of speech and expression is also critical. Ideally biennials should be spaces for artists and curators to express themselves freely, but we know this is not always the case. Safe discursive spaces should be encouraged. In many countries, however, these spaces are not allowed or are regularly challenged. Should there not be biennials in these countries? I struggle with this question. Is it better to have no biennial at all or to negotiate suppression, since artists can be ingenious with their messages?

ANNE BARLOW The “local” is not monolithic: it includes constituencies that have diverse politics, values, and interests. Thus, strong local connections entail complex relationships, different modes of engagement, and the ability to listen attentively. Building and managing such relationships takes dedication and time; it can be challenging to balance this commitment with a biennial’s international scope and intention. The Kochi-Muziris Biennale and Dhaka Art Summit stand out as cultural events that really engage local audiences alongside the international visitors that they attract.

View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

ZINEB SEDIRA If I were to create a cultural event in Algeria, it would definitely be this kind of discursive platform. There are too many biennials in the world now, and in the context of Algeria I don’t believe a biennial would be a productive platform. A dynamic discursive space such as the Dhaka Summit would be much more beneficial locally.

SYLVIE FORTIN Speaking of the biennial as a discursive space, I wonder about the dilution of discourse, debate, and dialogue into “education.” Every biennial now claims an educational mission. This “educational turn” has to do with funding on the one hand, and biennials’ intermittency, their “problematic” on-and-off temporality, on the other. The “education” on offer remains unidirectional, regardless of the degree to which it is inclusive or participatory; it reproduces dominant forces. It also signals a withdrawal from discourse as an unsettled realm of debate and speculation. This reconfiguration of biennials into service-providers—purveyors of neutralized public engagement, both educational and enjoyable—neatly depoliticises them. But who would dare argue against education?

What is left behind? The Festival d’Alger and similar politically motivated cultural events of the long 1960s knew the importance of leaving something behind, and not just taking. Institutionally, biennials may need to go much further than simply inviting local artists, to also consider local cultural needs, including policy and infrastructure. Biennials might reconsider what they leave behind, beyond a catalogue, public art, a touring version of the exhibition, or extended educational programmes.

Zineb Sedira, detail from Scene 3: Way of Life, 2019. Video installation with various 1960s objects, filmed interview (Nadira, 2019. Video, approx. 40 minutes), and playlist. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in 4 scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

Zineb Sedira, detail from Scene 3: Way of Life, 2019. Video installation with various 1960s objects, filmed interview (Nadira, 2019. Video, approx. 40 minutes), and playlist. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in 4 scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

ZINEB SEDIRA dOCUMENTA 11 was a breakthrough in Germany; it explored postcolonial identity. Did Kassel and the country re-evaluate their own politics, after dOCUMENTA 11 closed? Can the involvement of biennials in local politics lead to some shift locally? The Sharjah Biennial is a good example; it has had an impact locally and on its neighbouring states. It is a unique case, however, in which extensive financial capacity has met the dynamic vision of a resourceful director. The Sharjah Biennial may not be flawless, given the governmental context, but it is enabling cultural change.

SYLVIE FORTIN Might the biennial become a hospitable platform rather than an edition-centred machine? Might it be restructured to provide artists with the time and space to connect with local communities as they develop their work, in order to understand, negotiate, and contribute to the local context?

ZINEB SEDIRA It is essential for biennials to invite artists to do site-specific works, which is the only way artists can create a dialogue with a location. When biennials invite me to create a local project, it is ideal to have time to engage with local artists, art students, archives, and collections. In addition to making site-specific work, I feel I am also engaging and giving something back, not just taking.

This is important for biennials, yet only a few offer such opportunities. It has to do with funding, in part. Scaling down by inviting fewer participants might allow biennials to allocate more resources to artists and to increase local interaction. Curators could also create deeper connections.

Unfortunately, many biennials have now adopted a capitalist model, with revenue from internationalised audiences as a leading income stream. Biennials have become commodities. It is ironic that artists are participating in these political economies.

SYLVIE FORTIN Scale is a self-imposed narrative and a self-fulfilling prophecy: biennials’ press releases often begin with numbers—days, artists, countries, sites, partners, audience—before they even mention the approach, the theme, or the context. We really need to rethink the fundamentals.

ZINEB SEDIRA We need to focus on a more manageable scale. I am thinking about Prospect in New Orleans, which being small, was very realistic in terms of access and local engagement. It allowed the artists to learn a lot more about the city and about each other.

ANNE BARLOW The artist’s experience of participating in a biennial, in relation to a specific place or context, is an important consideration. It seems more possible to learn from a place and contribute to it in some way in small or mid-sized biennials. There are perhaps more opportunities for depth of engagement not only for the artist but also for audiences when they are not overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the event.

ZINEB SEDIRA We are all responsible for wanting to see “everything” and be “everywhere.” We definitely need to learn to slow down. It is also the role of biennial directors and curators to come up with alternatives. Certainly, the pandemic has helped us to analyse and rethink existing exhibition models. I hope it is for the best. While I do not have an answer, one thing is for sure: online exhibitions or biennials are not adequate substitutes or alternatives.

PART II: August 11, 2020

°°°

SYLVIE FORTIN You just came back from a first research trip for your Venice project. Were there any surprises? How are the research and thinking coming along?

ZINEB SEDIRA I did encounter difficulties due to the pandemic’s impact on travel. And although I did expect my research to be slower and more challenging, I did not anticipate that restrictions would be different for each institution. The Mostra archives in Venice were open; I met the archivists, but couldn’t do research due to the sanitary restrictions on the handling of documents. However, the Cineteca di Bologna and the Cinémathèque française were fully accessible.

The trip gave me ideas that changed the initial concept and content of the work. As the research advances, through archive visits and meetings, new avenues will open up. When I was in Paris, I met Costa-Gavras, who directed the film Z (1969), for which he won an Oscar. Co-financed by Algeria and filmed in Algiers, Z did allow the nascent Algerian film industry to register on the international cinema map. It was amazing to meet him and talk about militant cinema and his experience of working in 1960s Algiers. It was a rich encounter.

ANNE BARLOW I’d like to revisit our discussion of the trajectory of biennials, especially those that started small and grew to become more international. While some biennials have implemented longer-term and more sustained engagements with local audiences, do you feel that the balance has shifted away from local engagement and discussion as a result of internationalisation?

Zineb Sedira, Mother Tongue, 2002. Video, 5 minutes. Presented in the Sharjah Biennial 6 (2003). Courtesy the artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris/London.

Zineb Sedira, Mother Tongue, 2002. Video, 5 minutes. Presented in the Sharjah Biennial 6 (2003). Courtesy the artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris/London.

ZINEB SEDIRA Biennials that started small relied on resources that were locally available, including artists and educational contexts. Then they redefined themselves in terms of international audiences; this happened for many reasons, ranging for economic imperatives to the appeal of visibility. This international realignment required bigger shows. How else would curators, art critics, and collectors travel? An exhibition of twenty artists does not mobilise the international art world but a project featuring more than a hundred would.

The beauty of the first Sharjah Biennial, organised by Hoor Al Qasimi in 2003 with Peter Lewis, was that we were a manageable number of artists. We could meet, talk, network, spend time together, share, and be in “solidarity” with each other. The technical infrastructure was not yet developed and artists were very much hands-on, helping each other. In bigger biennials, artists work on their own (or with their assistant) and so we don’t connect as much.

Four years later, when I next participated in the Sharjah Biennial, the event was larger and very different. It had become more professionalised: staff and technicians were brought in from different countries and local staff learned skills while installing. The artists were allocated specific technical teams, brought their assistants with them, or had their galleries present. This created a distance, a barrier between exhibiting artists. There were so many artists that our relationship with the organisers became different; it was no longer intimate. Perhaps I’m missing this kind of intimacy.

While the 1969 Festival d’Alger was a very large event, there were still connections and alliances among artists and performers. Having just come out of colonialism, Algerians were also very curious to meet other Africans. I am talking about people’s interest in each other, a form of intimacy premised on commonality. Today, the artworks exhibited in biennials prevail over relationships, hindering the possibility of an artistic community and spirit.

Zineb Sedira, Framing the View, 2006. Photographs, 70 x 60 cm each. Presented in the Sharjah Biennial 8 (2007). Courtesy the artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris/London.

Zineb Sedira, Framing the View, 2006. Photographs, 70 x 60 cm each. Presented in the Sharjah Biennial 8 (2007). Courtesy the artist and Kamel Mennour, Paris/London.

ANNE BARLOW The premise of aria, the residency you established in Algiers, was to host artists and connect them with local, regional, and international networks. Connection was your priority when, as a practising artist, you defined the scope of the project. As such, aria is an interesting model to consider in relation to ideas of hospitality and the different ways in which local and international can be brought together.

ZINEB SEDIRA Sharing was at the centre of all our initiatives. Invited by aria, the artist had to interact with local people. We would agree on a format together: a chat over coffee with a group of artists, a workshop, or a talk, whether official or informal. The residency was tailored to both the needs of the visitor and the requests of the community of Algerian artists. aria also provided a research budget, which allowed guest artists to develop a body of work centred around their interests and findings. This model of local collaboration could provide a blueprint for an alternative to biennials by convening artists and curators to truly work together in and with a specific place. Exhibitions of new commissioned artworks would attract larger audiences. Biennials with a solid residency programme and financing could be a way forward.

ANNE BARLOW The pandemic has had a fundamental impact on the infrastructure of biennials in the past year and for the foreseeable future. To what extent do you feel that this presents an opportunity for artists to have a different kind of agency in relation to biennials and to their own participation in them?

ZINEB SEDIRA The responsibility of artists is not only to make work but also to act, challenge, and perhaps advise. The greater your experience and knowledge, the more important it is to share them and to use your voice in crises. I believe mentorship is vital.

For Saison Africa2020, the curator from the Fondation Louis Vuitton decided to organise a conference on artist-led initiatives like aria in Africa instead of an exhibition of African artists. This made me realise that there are many artist-led projects in Africa, South America, and Asia. In this respect, aria, Raw Material in Dakar, and others may exemplify exciting forms of bringing, making, and showing work—a mode of circulation that is different from biennials. And as these artist-led initiatives are sometimes initiated by artists from the diaspora, they can be seen as forms of geopolitical solidarity.

What might the curator’s role be, beyond accompanying the production and presentation of new work? How does curating account for the support and development of younger artists? The relationship between curators and artists is becoming very problematic. The role of the curator has shifted, especially institutional curators: it has shrunk, shrivelled to exhibition programming. Conceptual discussions and exchanges about artworks are almost non-existent, except for required administrative interactions. Affinities are rarely developed or discussed.

SYLVIE FORTIN Yes, the reduction of curating to simply programming parallels the conception of the biennial as a showcase providing a “window” onto the “best of cutting-edge” contemporary art. This, and the fashionable curatorial fixation on themes and formats, often leads to compliance with a form of box-checking representation—a depoliticising reduction of identity politics to representation. A window is inherently divisive: the window metaphor firmly positions visitors outside, looking in. It also confines the artist, framing them to confer the desired legibility.

COVID lockdowns have forced us to look out of windows (or shields) for too long. We long to step back into the world, together. How do we begin to reimagine forms of intimacy and solidarity? How do we bring about the re-enchantment?

ZINEB SEDIRA Why not shift from the usual—that is, hierarchical—organisational framework of director, curator, and artists, to simply a group of creators? It might be a very different kind of curation. It could be an artist inviting a curator. Involve artists and intimacy will follow.

Various practices and possibilities could break with the models we’ve seen everywhere. Documenta tried to propose something different, for instance, with a travelling biennial. For me, the Documenta initiatives in Afghanistan and Greece were problematic. I don’t think they brought much to the local scenes, especially in Kabul. It did, however, ease the conscience of a Eurocentric art world, providing an outlet for feelings of guilt. But Documenta did try to find different iterations. We always learn from such experiments, even if it’s that they should not be repeated.

ANNE BARLOW With the pandemic, for those who have access to technology, everything is now screen-based. This has changed what we might read and see, and what reaches us through different channels. Does that open up other opportunities for you as an artist, or do you see this only as a constraint?

ZINEB SEDIRA I am not convinced that the way that I’ve been asked to “share” during lockdown is the solution. For me, “sharing” requires an element of physicality, it requires something (inter)personal; otherwise there is no real communication with an audience. In my experience, videoconferencing quickly becomes tedious, flat because it is hemmed in by a technology that confuses messaging for communication. The few times I’ve given an online talk, the audience felt very distant, since I couldn’t see them, and so I could not give as much as I normally would. During this pandemic, this technology was quickly adopted as the way to work and stay connected. For me, this became increasingly unsatisfactory. What else could we do, beyond the internet?

My artist friends and I have turned down many invitations to give talks online: as artists, we make work for people to experience physically, not to view online. We give talks on our work in order to experience rich exchanges. I hope that our experience of confinement will help us find different models of communication, transmission, and collaboration. There is no real solidarity without physicality.

Zineb Sedira, detail from Scene 3: Way of Life, 2019. Video installation with various 1960s objects, filmed interview (Nadira, 2019. Video, approx. 40 minutes), and playlist. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in 4 scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

Zineb Sedira, detail from Scene 3: Way of Life, 2019. Video installation with various 1960s objects, filmed interview (Nadira, 2019. Video, approx. 40 minutes), and playlist. From Standing Here Wondering Which Way to Go, 2019. Installation in 4 scenes. View of the exhibition Zineb Sedira, A Brief Moment, 2019. © Jeu de Paume. Photo: Raphaël Chipault.

SYLVIE FORTIN There’s something important about availability. Intermittency is very specific to biennials: recurring at regular intervals, they are not always on view. The impact of COVID-19 on cultural organisations may allow us to grasp the unexplored potential of biennial’s intermittency more clearly. Can we now rethink the temporality of biennials as a composite of periods of latency and presentation rather than as periodic public events? The plenitude of intermittency! Can we think of their on-off alternance as constitutive—as their very core—rather than a mere by-product of the biennial format?

This recentring might provide a useful antidote to biennial’s need to fill the between-biennial time with programmes. It’s very difficult for people to understand that you may not be there all the time, yet still be very important. Educational programmes and public art have been the go-to devices—the reflexes—of biennials that want to extend their public engagement. But these devices reflect the imperatives of funders, and their understanding of the social role and agency of art.

The rejection of the imperative to be available, on demand and at all times, might be one of the unexplored strengths of biennials, but it’s rarely articulated as such. How do we articulate this as we move forward?

ZINEB SEDIRA Five months of lockdown is probably the closest we’ve come to the experience of many artists living in Africa and other areas of the “Global South” who cannot travel abroad because of visa restrictions. Their knowledge and experience of international contemporary art come through the internet (or books). Those of us who live in Europe and elsewhere in the North were frustrated because temporary confinement prevented us from accessing art in the usual way, by visiting galleries, art fairs, biennials, and museums. But for these artists, lockdown and isolation are the norm, shaping experience over a lifetime, flattened by screens.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Zineb Sedira lives in London and works between Paris, Algiers, and London. Representing France at the 59th Venice Biennale (2022), Sedira is also shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize (London, 2021).

Selected solo exhibitions: Photographers’ Gallery (London, 2006); Pori Art Museum (Pori, Finland, 2009); Bildmuseet (Umeå, Sweden, 2010); Kunsthallen Nikolaj (Copenhagen, 2010); Palais de Tokyo (Paris, 2010); Musée d’art contemporain (Marseille, 2010); Blaffer Art Museum, (Houston, 2013); Prefix (Toronto, 2010); Charles H. Scott Gallery (Vancouver, 2013); Sharjah Art Foundation (2018); Beirut Art Center (2018); Jeu de Paume (Paris, 2019); Institut Valencià d’Art Modern (Valencia, Spain, 2019).

Selected group exhibitions: Tate Britain (London, 2002); Centre Pompidou (Paris, 2004 and 2009); Mori Museum (Tokyo, 2005); Baltic Centre (Gateshead, 2005); Musée d’art moderne (Algiers, 2007); Brooklyn Museum (2007); MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst (Frankfurt, 2014); Power Plant (Toronto, 2015); Smithsonian (Washington, 2015); Guggenheim Museum (New York, 2016), Studio Museum (Harlem, 2016); Museu Coleção Berardo (Lisbon, 2016); MAC VAL (Vitry-sur-Seine, France, 2017); Whitechapel Gallery (London, 2019).

Selected biennials: Venice Biennale (2001 and 2011); ICP Triennial (New York, 2003); Sharjah Biennial (2003 and 2007); Folkestone Triennial (2011); Thessaloniki Biennale (2011); Prospect.4 (New Orleans, 2016).