ADELINA CÜBERYAN VON FÜRSTENBERG WITH BASAK SENOVA AND SYLVIE FORTIN

Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community…

- 17.12.2018

- ConversationCuratingBiennial HistoryAdelina Cüberyan von FürstenbergSylvie FortinBasak SenovaLawrence WeinerSol LewittDan PerjovschiChen ZhenJoseph KosuthPat SteirRichard TuttlePaul ThekVito AcconciJames Lee ByarsEdward KienholzMarcello MalobertiAnna BoghiguianHaig AivazianSheba ChhacchiJoseph BeuysPer KirkebyIlya & Emilia KabakovTadashi KawamataBruly BouabréNam June PaikRobert RauschenbergGiuseppe CaccavaleAleksey Manukyan

“Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.”

Influenced by conceptual art and continental philosophy, Adelina Cüberyan von Fürstenberg is a curatorial grande dame who has relentlessly charted her own way. She has created several insti- tutions, directed the world’s first curatorial studies programme and curated biennials and large-scale exhibitions across Europe and the Americas as well as in Asia and North Africa. Today, von Fürstenberg stresses the need to support the development of biennials and periodic events in ‘peripheral’ locations around the world. In this conversation with curators Basak Senova and Sylvie Fortin, von Fürstenberg discusses her commitment to an art world that engages an expanded citizenry. Defining her approach as political and emphatically asserting every human’s right to participate in culture, she champions art that sustains close relationships with the city and with civilisation.

Dan Perjovschi, Notes and Postcards on Water, 2017. Drawings, postcards, magazines and journals. Dimensions variable. Installation view of AGUA – ARTISTAS CONTEMPORÂNEOS E QUESTÕES DA ÁGUA at SESC Belenzinho, São Paulo, 2017. Photo: Everton Ballardin

BASAK SENOVA You’ve navigated diverse ideological, cultural and economic conditions with your many projects, exhibitions, films and biennials. The artists with whom you work are always politically engaged with the world’s main issues, which leads me to think that being critical is important for you. How do you critically approach each situation? What is your standpoint, the core of your approach?

ADELINA CÜBERYAN VON FÜRSTENBERG I am a senior curator, maybe one of the last generation of Switzerland’s avant-garde curators – or kunstmacher. Harald Szeeman’s Documenta 5 in Kassel (1972) introduced me to contemporary art. I can still remember and describe some of the art installations, such as those by Paul Thek, Edward Kienholz, Vito Acconci and James Lee Byars. In addition to Documenta itself, Szeeman’s methodology led me to understand that you can learn a lot about life by watching an artist working on a show.

First, I learned about the artist’s critical approach to the space of art. For conceptual artists in those days, space was crucial. Artists such as the Americans Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner, Sol Lewitt, Richard Tuttle and Pat Steir initially built their work through their relationship to the space at their disposal. In their case, the space meant the context for the existence of the artwork. If you think about this on a deeper level, they were talking about our very existence in the world. At a recent opening of Richard Tuttle’s in Geneva, he told me: “All through these years, everywhere the walls have remained the same, but the floors have changed. We continue to look at the walls however, and not enough at the ground…”

Among the many philosophers popular with my generation, Roland Barthes was one of the most influential. For Barthes, conceptual artists were the most intelligent because they fought the frame (the art system) and not the content (the artwork). This is why, he added, the bureaucracy and the administration, as well the system of academies and universities, will never support this kind of art. This was my first political lesson in art.

The other core dimension of my practice was the fact that I did not want to work in galleries or in a commercial context. My goal was to create institutions. As a curator who studied political science in the 1970s, I saw the creation of an institution as the greatest vehicle to transmit art to the largest public.

Chen Zhen, Round Table, 1995. Installation view of Dialogues of Peace at the United Nations, Geneva, 1995.

Already on the university campus, I started the Centre d’art contemporain de Genève, where I introduced different forms of art such as conceptual, Fluxus, minimal, body art, and so on. We had very little money and the Centre’s existence was precarious. Over time, it became a city institution and moved to large permanent spaces with appropriate budgets. This is when I left for France to become the director of CNAC – Le MAGASIN (Centre National d’Art Contemporain) in Grenoble, one of the biggest art centres in Europe. At the time, in 1989, it really looked like something was changing in Europe, especially in France under the leadership of the culture minister Jack Lang. He supported the creation of a number of large contemporary art institutions in every region of France in order to serve a large public – including families and children. Citizens could spend their free time visiting museums and institutions and teaching their children about the notions of art and beauty. Things are different today. Art has become trendy and posh: a signifier of social status and economic affluence mobilised on social media and a symptom of the globalisation of our aesthetics.

You asked me if my approach to art has always been political. I would say that it has been, in the sense of polis, meaning city and civilisation. I have always looked at art from the point of view of civil society, as a human right. I can’t see the art world as being a simple aggregate of curators and collectors, galleries and auction houses. For me the art world also includes citizens and human beings. It is very much in line with article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that “Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.” Art and culture are central to our evolution and progress; they are fundamental rights defined by Kant as innate rights.

Of all the artists that I worked with or was close to, Joseph Beuys was the most important for my evolution. I met him at Documenta 5. For Beuys, art wasn’t ornamental and contem- plative. The artist was as important as the artwork and there was no longer a split between art and life. In concrete terms, Beuys worked all his life to awaken us to the crucial questions of our planet, in particular the environment and climate change – problems that we face so dramatically today.

Chen Zhen, Round Table, 1995. Installation view of Dialogues of Peace at the United Nations, Geneva, 1995.

SYLVIE FORTIN documenta 5 was fundamental for you, a tipping point. Looking back at biennials or large-scale exhibitions– as both witness and participant – what did they contribute to your thinking? Can we trace a trajectory, something specific about biennials?

ADELINA My initiation to biennials came in 1993 at the 45th Venice Biennale when I was invited with the École du MAGASIN, which I was directing in Grenoble, to participate in the curatorship of different sections and to work on a number of exhibitions and pavilions. This led me to better understand the context and operations of a biennial. That year the École du MAGASIN won the Jury’s Special Award.

Two years later, in 1995, United Nations Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali, an admirable Coptic-Egyptian diplomat, selected me to develop a contemporary art exhibition as part of the UN’s 50th anniversary celebrations. Influenced by my recent Venice experience, I proposed an ambitious exhibition in the UN Park in Geneva. This was during the war in what was formerly Yugoslavia. For the first time since the Second World War, Europe was facing an internal war – only a few hundred kilometres from home and the UN’s office. This war of the intolerance of difference pitted Muslims, Catholics and Orthodox as well as leftists and rightists against each other. The concept of my exhibition was difference and tolerance. While it was not a biennial, it was a gigantic show with large sculptures and pavilions and more than 60 artists, including Tadashi Kawamata, Ilya Kabakov, Chen Zhen, Per Kirkeby, Bruly Bouabré, Robert Rauschenberg and Nam June Paik.

With this exhibition at the UN, I realised that it’s rare to find an artist who isn’t interested in the world’s important questions. Even abstract art relates to the world. As such, artists are for the most part political, the term being derived from the ancient Greek politikē (that which concerns the polis or the city-state), with the implied notion of technē (art) and by extension, art pertaining to the city-state

After this experience, with so many pressing questions and discussions, it was difficult to go back to a conventional contemporary art museum. So with some of my collaborators, I founded an NGO, ART for The World (AFTW), in 1996 with the vision and hope that art would play an important role in the forthcoming 21st century. Some of my collaborators left, some partnerships changed, but I have continued to work with AFTW, which the American architect Philip Johnson described quite beautifully as a “museum without walls” in one of his interviews in 1999:

The word museum has a sort of static connotation. It can be boring. The organization created by Adelina, “ART for the World,” stems from the desire to remove these connotations. In keeping with an old French idea, it is a museum without walls: first, you find the right place for what you want to exhibit, then, you can select and change the container each time.1

Sheba Chhacchi, The Water Diviner, 2008 Installation with videos, books, light boxes, sound, light and water. Dimensions variable. Installation view of AGUA – ARTISTAS CONTEMPORÂNEOS E QUESTÕES DA ÁGUA at SESC Belenzinho, São Paulo, 2017. Photo: Everton Ballardin

Sheba Chhacchi, The Water Diviner, 2008 Installation with videos, books, light boxes, sound, light and water. Dimensions variable. Installation view of AGUA – ARTISTAS CONTEMPORÂNEOS E QUESTÕES DA ÁGUA at SESC Belenzinho, São Paulo, 2017. Photo: Everton Ballardin

SYLVIE Could we say that conceptual art coincided with and possibly co-produced the rise of the biennial format?

ADELINA In the past decades I visited and participated in various biennials and triennials, from large ones such as Venice and São Paulo, to small ones such as Thessaloniki and STANDART in Armenia. I witnessed their gradual transformation. We all know that art fairs became increasingly important in the art system in the 21st century. The art market changed as galleries began to follow and cater to the tastes of buyers. Many biennials have also become showrooms – if I can make such a radical statement. At the last Venice Biennale, a gallerist told me that there was no better place for collectors to shop than at biennials. There’s nothing wrong with that per se, but is this really the purpose of a biennial?

Peripheral biennials such as Riga, Kochi, Sydney and Dakar, to mention but a few, are different. Biennials continue to have a raison d’être, especially when they take place outside of the main art markets.

BASAK STANDART, the triennial that you launched in Armenia in 2017, was a very ambitious project. How is it structured? How will it be sustained? You brought a lot of financial resources and visibility from the outside. What will happen for the next edition?

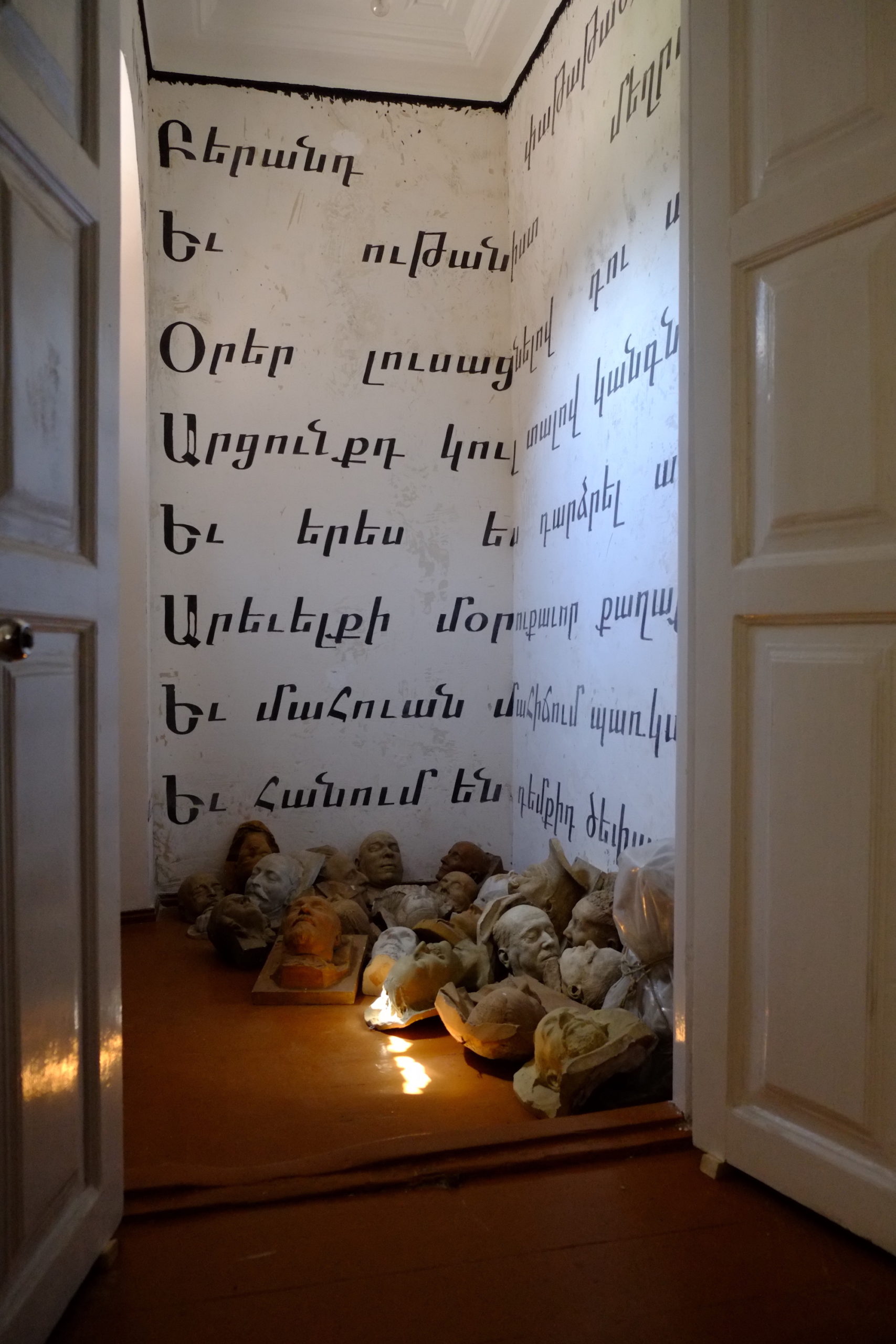

ADELINA It is important to know that this triennial was not my idea. It followed on the heels of my curatorship of the Armenian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2015. Our pavilion was awarded the Golden Lion for best national pavilion, which in turn brought visibility to Armenia and Armenian contemporary art. Vartan Karapetian, the president of the Armenian Arts Council (AAC), invited me to organise the first triennial in Armenia. I have no doubt that this triennial will continue because the AAC combines strong leadership and a committed team. In addition to the AAC, a group of young people started the Armenian Art Foundation at the end of 2015. This foundation provides grants to local and international Armenian artists, contributing to general cultural development in the Republic of Armenia. With these two organisations doing complementary, long-term development, I’m confident that the triennial will continue to grow. As an experimental ‘farmer,’ I sowed some artistic seeds in Armenia. Some seeds will grow, others will not, as is always the case. When a new biennial is launched, its organisers always hope that it will continue. But it’s often difficult. In today’s world, political, economic and social changes can happen very quickly. The AAC, however, is doing its best to ensure the sustainability of its programme for the next edition in 2020.

SYLVIE I’m fascinated by the importance you give to the establishment of institutions. Is your institution-making practice also a strategy to sustain curatorial independence, a means to support your work and the work of others around you?

ADELINA It’s too reductive to think that institutions are created or available to sustain this or that curator. However, institutions are supposed to give curators more independence than private initiatives. Institutions are also expected to give artists more freedom. But this is no longer our reality as public funds for the arts are under relentless pressure while corporate sponsors and the market exert more influence. As former art advisors become curators, they often confuse artworks with commodities.

SYLVIE Recently, biennials have faced censorship, which relates to this quest for control. Biennials are reaching a wider public and therefore becoming greater targets. This operates at various levels. The attack can come from above or from below. It can come from the state and/or private stakeholders such as collectors. It can also come from the art community or the public. Given what you just said about collectors, what are your thoughts on this?

ADELINA In the last 20 years, the budgets of many public institutions have decreased. In parallel, private foundations and corporate global sponsors with large collections have become involved with biennials. The influence of this new sort of collector goes beyond individual tastes. It’s about marketing products and services. They support art that advances their brand and steers clear of possible conflict. Even unconsciously, their decisions are guided by their product or their customers. Conversely, individual collectors usually have a much clearer vision.

SYLVIE The state and collectors are also working from the same place now. It’s a question of social reproduction under neoliberalism, a top-down assault. More interesting to me is what I might call ‘censorship from below,’ which is often sparked from within the arts community, spreads out amorphously, feeds on the politics of censorship and ultimately results in a hijacking of the practices of identity politics. It turns our long, arduous fight for equity and justice against itself. This work from above and below is actually producing the same thing: no space. That’s a new thing.

ADELINA I agree with you because the so-called public is no longer only a public of art lovers. The art world is now open to an expanded public. Many things indirectly play a role in the experience of these visitors: social media, the internet, magazines, public relations and so on. Their tastes and their aspirations are manufactured by the products that they love to consume. Everything is very tribal, people conform to this or that identification. There is also no longer anything like an intellectual point of view. Human rights have already started to be put in question. Many concepts that we used to take for granted, such as universality and rights, are changing from the bottom along with the public’s reactions.

SYLVIE In other interviews, you’ve often stated that curatorial projects require that we start from zero every time. Can we speak of biennials as ways of thinking, learning and doing? Could it be that biennials’ temporality and dispersal – they are temporary, recurring, periodical, spatially adaptive – make them engines of difference?

ADELINA From my point of view, while we have to continue with the large Western biennials, we also have to support the development of more biennials and periodic events elsewhere around the world. These events are very important. They play a crucial role in places where there are no strong museums or other art events because many people can’t travel to art centres.They crystallise and amplify local energies by engaging with artists and people interested in the arts and culture. These peripheral biennials usually enjoy more freedom because their temporality exempts them from the kinds of pressure faced by Western art institutions. Many are still free from any sort of business manipulation. These biennials are usually very interesting and friendly. As a result, the public can experience and learn from the artworks in the exhibition, from the artists’ attitudes and from an empathetic art community.

Recurrence every two or three years is crucial. It builds momentum and sustainability. Finally, the contribution of biennials is manifold, beyond culture and education: they bring work to local craftspeople and professionals, they attract tourism to the host city/place, they grow the local economy and much more. It’s also important to point out that it’s often less expensive to produce artworks in these locations.

The 4th Thessaloniki Biennale, which I curated in2014, was extraordinary because Thessaloniki is a city of difference. Art can make its amazing story of cultural and ethnic difference come to life. When stories are brought to the fore, people become more aware and are more willing to discuss it together. Artists are usually open-minded people and their presence and interest can initiate openings, relationships. One day, as we were going with artists to see a part of the Biennale in a former mosque, we met a woman living next door. When she learnt of our destination, she started singing an old Turkish Armenian song. She told us she was the daughter of an immigrant from Turkey and started to speak about her family’s life during the First World War.

In Armenia, something similar happened when we were in Gyumri, formerly known as Alexandropol, where a terrible earthquake took place some years ago. While we were in the streets, going from one exhibition to another during the opening of Mount Analogue, one of the shows in the Triennale of Armenia, a woman suddenly stopped us and said: “We were sad and you brought us joy.”

I experienced something analogous years before, when we published the catalogue of the Bienal de La Habana in 2000 and went to Cuba. It was quite interesting to meet local people in the art events talking about themselves, their lives. If you are open and curious to learn, not simply closed off in your little art-world club and its strategy, you can meet wonderful people while visiting biennials and sharing in the art around you.

SYLVIE That leads us to our last question. You have also produced many large travelling shows. In developing these projects, how do you think about going from one context to another?

ADELINA The idea for these travelling shows came from my experience in cinema production. Working in cinema takes a long time and, finally, a production is launched. If it is good, the film will stay forever and goes from one theatre to another, from one TV channel to another, across the world. This led me to ask myself why exhibitions, which are as time- and energy-consuming, end after two or three months. I found this quite frustrating. Travelling shows seemed to provide an answer to this conundrum.

When the concept for a travelling exhibition is broad enough, it can be adapted to different countries. In that sense, each presentation is a new show. This is very different from traditional museum co-productions, which are expense-sharing initiatives that produce one show–the same show at all participating venues. For AFTW, every show is a new show with the same concept, developed for a specific context (going back to conceptual art). I like this way of working because the project doesn’t end after just one show. We keep learning and developing, delving deeper. Some of the artists are the same for each presentation. Some are different. Some are local. The catalogue is also different each time. We usually produce three iterations, four at most.

For example, more than 30 artists worked on the theme of water issues for our recent group show AQUA. In Geneva, it aligned with the United Nations’ sustainability development goals. In Brazil, the problematic was different. Their main issue was the impact of pollution on biodiversity, on the Amazon and so on. In Italy, the issue was water scarcity: the drying up of the lake that supplies potable water to surrounding municipalities and the destruction of the local ecosystem.

With AFTW, failure is not an option. If we make a mistake with a project, it’s over. You can’t repeat it. It’s not like a museum where you can do a mediocre show, followed by a good show and so on. We have to deliver good exhibitions, create good working relations with the institutions and the art world of countries where we want to continue our collaboration. For instance, we have been working with the Regional Direction of SESC (Serviço Social do Comércio) in São Paulo for years. SESC is the largest cultural institution in Latin America. Its main role is to improve people’s lives by providing access to education, culture, health and recreation. Since its foundation 70 years ago, it has grown tremendously, not only in terms of the number of spaces it programmes but also in its broader support of the arts, theatres, music and the Bienal de São Paulo. They produce amazing contemporary art shows and related programmes that actively engage with everyone: families, children and aging people, collectors, students and so on. Their ability to create and offer art and culture is exemplary. During my recent visit, I saw an amazing show at SESC Pompeia: Bauhaus Imaginista: Learning From, which explored the interdisciplinary approach and the overall idea behind the Bauhaus, 100 years after its creation, has never been as current as it is today.

NOTES

1 Interview with Philip Johnson by Angela Vettese in Philip Johnson: Children’s Museum, Guadalajara, Geneva: ART for The World and Mondadori Electa, published as a supplement to Casabella 669 (July-August 1999), unpaginated.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Adelina Cüberyan von Fürstenberg, a renowned international art curator and independent film producer, is President and founder of ART for The World, an NGO based in Geneva, where she lives. She has worked with several biennials from Havana (2000) to Thessaloniki (2013) and the 56th Venice Biennale (2015) where, as Chief Curator of the Pavilion of the Republic of Armenia, she received the Golden Lion for the best national pavilion. In 2017, she directed the inaugural edition of STANDART, the triennial of contemporary art in Armenia.

Sylvie Fortin is an independent curator, researcher and critic. She was Executive and Artistic Director of La Biennale de Montréal (2013-2017), Executive Director and Editor of ART PAPERS (2004- 2012) and Curator of the 5th Québec City Biennial (2010). She is currently researching the currencies of hospitality.

Basak Senova is a curator and designer. She curated the pavilions of Turkey and the Republic of Macedonia at the Venice Biennale (2009 and 2015). She also co-curated the 2nd Biennial of Contemporary Art, D-0 ARK Underground (Bosnia and Herzegovina), curated the Helsinki Photography Biennial 2014 and the Jerusalem Show VII, Fractures (2014), and acted as Art Gallery Chair of “ACM SIGGRAPH 2014” (Vancouver). She is working on the CrossSections project in Vienna, Helsinki and Stockholm (2017-2019).