Yuko Hasegawa

Reaching Furtively Towards the Future: A Biennial for a Time of Transition

- 21.06.2021

Pnat, Fabbrica dell’Aria, 2019.

The Significance of the Biennial Today: The Turn

In the twentieth century, we could to some extent predict what would happen in the twenty-first century, but today foretelling the twenty-second century is more of a challenge. Things are changing so fast that the “now” no longer has much duration; the science fiction writer William Gibson called this reality the “FQ,” or “Fuckedness Quotient.”

Pnat, Fabbrica dell’Aria, 2019.

In this context, biennials of contemporary art are at a major turning point. The Global information exchange is greater than ever and acceleration has transformed not just contemporary culture and expression, but newness itself. Accordingly, the meaning of exhibiting and discussing contemporary art every two years, often in a city, has to be reconsidered. Since my curatorial work has focused on urban biennials, I will address primarily the phenomenon of biennials in urban settings.

In this essay, I use the word “art” to refer to the ecology of contemporary art and its neighbouring activities and sites in a concrete and comprehensive way. Contemporary art is a process that facilitates exchange between a wide range of disciplines and genres as it translates critical observations about society, politics, and the environment into aesthetic forms. It is a form of knowledge production that encourages criticality, a widening gaze, and a diversity of alternative perspectives, and produces shifts in the perception, sensibility, and aesthetic consciousness of its audience. In an age of “VUCA”— volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity—people demand an art that can serve as a mechanism to produce a body of complex information, emotion, and concepts: art is something of a weapon of last resort that promises to help us human beings recover harmony with our immediate environment, and ensure our survival.

In this context, the biennial holds great potential as a responsive organism. The first dimension of this response takes on the reconfiguration of capitalism by reassessing our relationship to it. Until the end of the Cold War, the brand of capitalism advanced primarily by the United States was imbued with a certain measure of ethics and emotional affect. By contrast, neoliberalism, our era’s ruthless GDP-maximising capitalism, is an uncompromising and all-encompassing structure bereft of both love and logic. Emotion and love have become user (consumer) interfaces, serving business strategies devoted to data collection and AI-enabled analytics. Now that the relationship between emotion and information has proven leverageable, many businesspeople have become interested in art. In the face of such structural changes, art’s conventional critique of capitalism and its related strategies of resistance no longer function. Art’s avant-garde gestures and innovation have always been co-opted by capitalism; even criticism can become an object of consumption. It is time for “art” to analyse itself: to question its essence, shift its focus away from its antagonism to capitalism, and turn toward collaborating with it and intervening in it.

The second dimension is the increasing richness of local cultures, the fertility of situatedness. This contrasts with the homogenisation of cultural life brought about by globalisation, which has led to the reactionary backlash of nationalism. In order to avoid such inward-looking isolationism, curators must carry out a series of operations that will make each location autonomous and self-reliant, but simultaneously connected with others and engaged in a process of sharing. There is no formula for this, but only a model of cultivation that uncovers and nurtures different resources in different environments, enriches them through internationalisation, and allows them to flourish.

But first let us consider what it means to enrich and steward this soil properly, with empathy and affection. The biennial’s life cycle and biannual harvesting is compatible with a model of action premised on the perennial and sustainable cultivation of a single site. This image of cultivation and harvesting contrasts with planned agriculture. As the gardener and landscape architect Gilles Clément shows in his book Garden in Motion, it is the plants themselves that create the garden: a balanced collaboration between humans and plants revitalises a site. By analogy, the cultivation and harvesting carried out by biennials are not a matter of planning and implementing an art project; rather, they require waiting for something to germinate and so unearth the potentials of sites and resources, by providing them with compost and other nourishment while setting up and facilitating an overall configuration.

The biennial has spread across the world since the 1990s because of its festive character and political and socio-economic impacts. These are similar to those of sporting events in terms of their popular appeal and attraction of international visitors, and the branding of a biennial often borrows from the strategies of international festivals that also mobilise local citizens. Special permissions repurpose into art venues places not normally used for exhibitions—markets, ports, libraries, zoos, city halls, non-public buildings, and so on. The biennial is invaluable insofar as it presents its host with an opportunity to gather a wide range of audiences to explore the complexity of a current situation, prompting people to feel it and think about it together through a situated experience. The biennial has the potential to weave a web of empathy and solidarity among visitors, while also fostering deeper reflection, sensitivity, and knowledge. This is because the biennial differs from traditional academic and artistic institutions. The role of museum curators, for example, is primarily to develop the institution’s collection through the lens of art history and education. By contrast, the essence of curatorial work for biennials and other alternative contexts lies in the ability to highlight and respond to different social, political, and cultural contexts and discourses. This is what distinguishes curators of biennials from art historians and critics.

In the present era of FQ and VUCA, the borderless and shifting space-time of the biennial institution and its reliance on eventhood can yield powerful results. Let me attempt to make the image clearer: the biennial is an organism that continuously hacks the situation around it, like a forest that fuels transformations. No one can predict what kind of chemical reactions will occur and what might be hacked—art, the audience, or the significance of the site.

According to the Harvard-trained AI researcher and businessman Takuya Kitagawa, it is perception itself—not thought processes—that constitutes intelligence, while emotion and sensibility help this intelligence to develop. Science describes and analyses mechanisms, but it lacks the power to forge relationships among them in an integrated way. According to Kitagawa, the role of art, which is able to bring information and emotion together, is to effect this integration. We should abandon human- or art-centred ontologies to confront the situation at hand, and seek out exchanges and collaborations with a variety of living and non-living entities, structures, and institutions, without fear of being exploited or hacked. Artists should start with the question “Why?”—that is, their motivation to create a particular work—and choose the appropriate artistic language and medium. Art, which is a creative act by an individual or a small collective, inherently possesses tremendous diversity and complexity. Every two years, art’s wealth of microbes and bacteria fertilises the cultural soil of the biennial, whose tangible products nourish our intelligence.

To consider the biennial as an organism would entail its reconceptualisation as an immanent system, or an ecological cycle, which raises questions of sustainability. Alternatively, environmentalism might be seen as a kind of relationalism. In the field of art, the biennial is one of the key mechanisms for creating intersections between local civic ecologies and the global cultural infrastructure; it also generates discourses specific to that intersectionality. But the biennial is neither the sole legitimate heir nor the guardian of the discourse of contemporary art, which is continually deconstructed and hacked by localised discourses. For example, site-specific works in places of historical memory may resignify an event or rewrite history. The symbolism of a place may be different for young people, inflecting their interpretation of the work; here, their creative interpretation replaces history with a completely new narrative, and in the process, they liquidate the “asset” traded by the official memory of a place. Memories of these site-specific works continually overwrite those associated with a specific cityscape.

The biennial could be reborn with a new mission if we are willing to look at “art” as a mechanism and facilitator. In a complex and confusing situation in which it is impossible to pinpoint where a sense of justice or ethics might lie, art functions as a mechanism that structures systems of ecological circulation, with the biennial serving as the device that drives this process.

Research: Urban Ecologies and the Global Ecology

If the biennial’s mission is to forge connections between the ecologies of the host city and global culture, research works in both directions. The term “ecology” encompasses multiple ecologies: social, political, spiritual, natural, and informational. In order to conduct cross-disciplinary research, direct information should capture the atmosphere of a place not only through art, but by relying on a range of methodologies including those of urban anthropology, ethnography, sociology, history, psychology, and other fields in the humanities as well as the sciences. In my case, I begin by getting a feel for a place through physical and sensory experiences. I temporarily set aside all the information I have compiled in advance, and head to the markets, streets, and clubs. I sit in a cafe for hours watching people go by. This is a space of life and emotion and I seek out its vibes, rhythms, and smells.

My starting point in 1999, in preparation for the 2001 Istanbul Biennial, was ethnographic research into the music called arabesque, which is often played in Istanbul taxis. I felt a certain similarity between this music, sung in vibrato and with deep emotion, and Japanese enka, which uses the pentatonic scale, like ancient Japanese folk music, instead of the Western heptatonic. This was richly suggestive for a biennial that took as its theme the subject as a composite interplay between Western individualism and a kind of Eastern collectivism, which I called “egofugal.”

In order to arrive at an understanding of Istanbul’s civilisational context, I conducted research on places that represent a kind of border between Eastern and Western civilisations. One of these places was the Taklamakan Desert, where I encountered the music that accompanied dancers from Central Asia and Russia on their journey west from Kunming, China. This music appealed to the same emotions as those stirred by the music of the singer Tarkan that resounded in the streets of Istanbul, overlapping with the sounds of the arabesques. The experience of this discovery was the first important preparatory step in planning the Biennial, which I sought to align with the sensibilities of this city by establishing a resonance with its ambience.

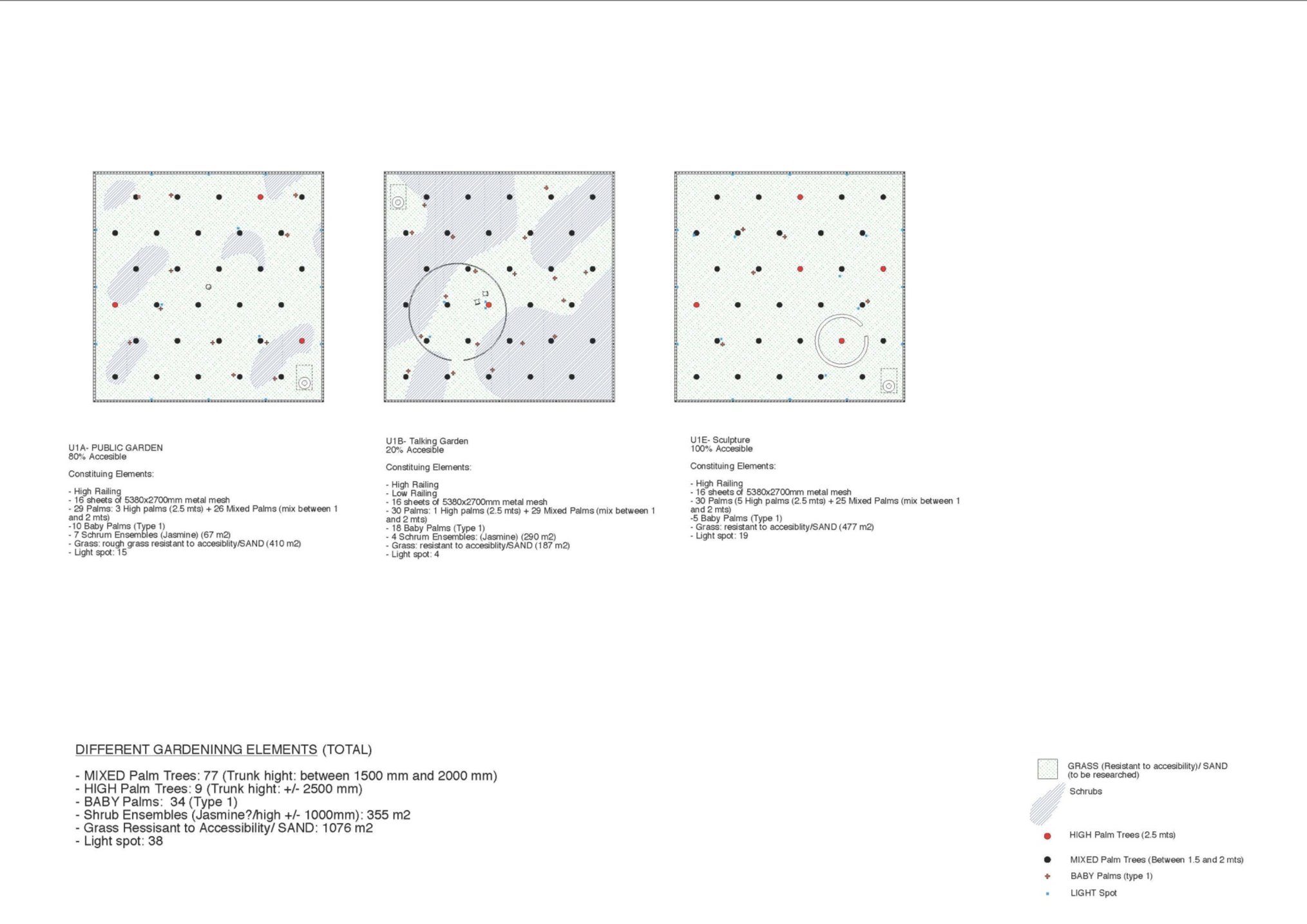

clouds⇄forests (concept: Yuko Hasegawa; design: Seiha Kurosawa)

clouds⇄forests (concept: Yuko Hasegawa; design: Seiha Kurosawa)

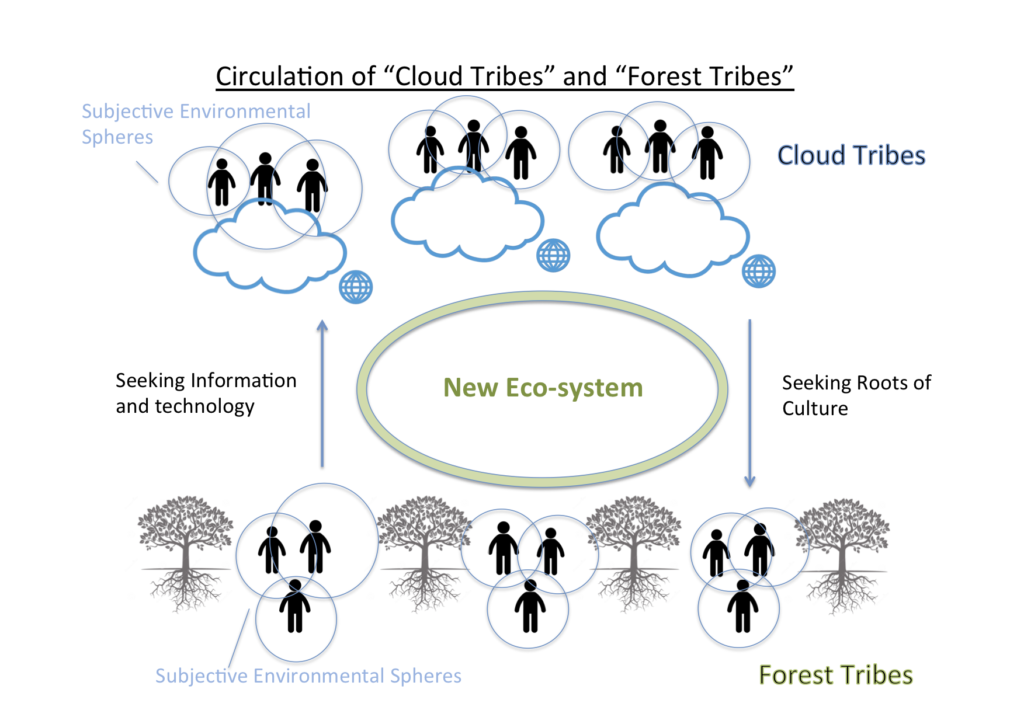

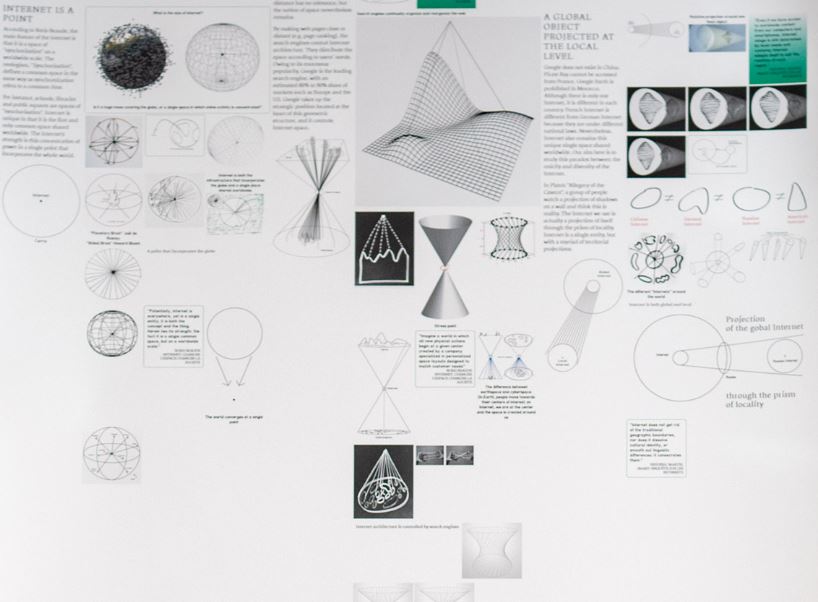

This investigation of the environment and atmosphere required a different approach for the 2017 Moscow Biennale, Clouds⇄Forests. As suggested by its title, it explored the differences between online space (the cloud) and offline living (forests) as well as the circulatory systems connecting them as a new ecology.

clouds⇄forests Conceptual Map (concept: Yuko Hasegawa; design: Seiha Kurosawa)

clouds⇄forests Conceptual Map (concept: Yuko Hasegawa; design: Seiha Kurosawa)

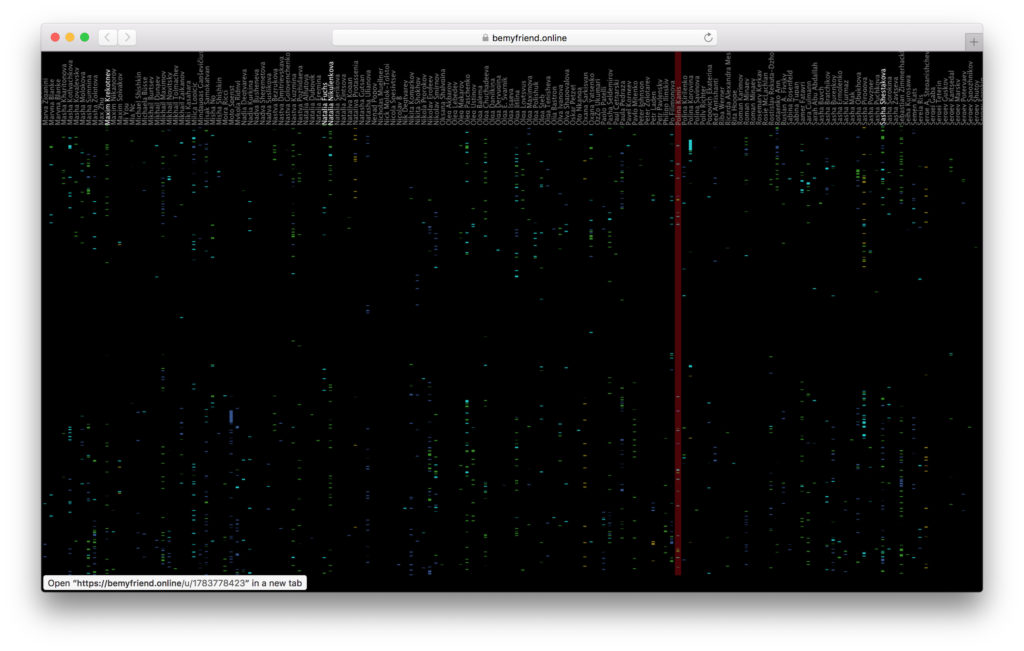

I took an information-science approach and involved digital researchers and programmers who have been mapping the geopolitics of the cloud world. Its unindexed networks, such as the Deep Web, reveal invisible social spaces where commentary and information are exchanged.

From the self-regulation induced by internalised censorship to the mobilisation of people made possible by the distribution of messages through networks, some artists saw their online actions as more real than overtly anti-establishment political tactics. How do we encode not only historical and symbolic places, but also abandoned places, waste, and formless information bugs? The number of our Facebook “friends” and the time we spend gazing at screens become data, sociality, intimacy, and emotion. The emotional signals I saw on the streets of Istanbul during my research sixteen years ago now had to be gleaned from tenuous micro environments in Moscow in 2017. In other words, the “situation” that presents itself—and one’s reading of that situation—depends on how curatorial research is performed.

Valia Fetisov, Be My Friend, 2017, https://bemyfriend.valiafetisov.com

Valia Fetisov, Be My Friend, 2017, https://bemyfriend.valiafetisov.com

Methodologies of Exhibition Making: Interpreting and Translating “Situations”

Different curators focus on different situations. They have a limited research time frame to explore a particular situation, interpret it, and then offer translations. My curatorial practice has continued to explore the transition from the “three Ms”—man, money, and materialism—to the “three Cs”—consciousness, collective intelligence, and coexistence—which I first proposed in 1999. My critique of individualism and subjectivism has led me to consider the biennial as a process that allows us to discover a city’s potential audiences and encourage their participation. This is not based on some sanctimonious idea that they need art, but rather on the fact that their involvement is needed to make art richer. The diversity of expressive languages and the plurality of perspectives found in art are key: art is always a collaborative process of co-creation, which is called “appreciation,” premised on humility and respect for the audience.

Carlos Amorales, We’ll See How All Reverberates, 2012. Steel, copper and epoxy. Dimensions variable. Installation view: Sharjah Biennial 11, Calligraphy Studio Courtyard. Image courtesy of the Sharjah Art Foundation.

Carlos Amorales, We’ll See How All Reverberates, 2012. Steel, copper and epoxy. Dimensions variable. Installation view: Sharjah Biennial 11, Calligraphy Studio Courtyard. Image courtesy of the Sharjah Art Foundation.

The main potential audience of the 2013 Sharjah Biennial were migrant workers, who make up eighty percent of the Emirate’s resident population. Most are single but some relocated with their families, and they constitute an important part of the community. Owing to both climate and custom, courtyards in Sharjah serve as public spaces, rather like city squares in the West. Depending on the size and use of the building, courtyards can also be semi-private places. So, I proposed the creation of a new kind of composite space, both public and private, where immigrants and Emiratis could encounter each other. These spaces were designed to allow people not only to gather, but also to engage in conversation. They were devised as place-making projects, both rethinking the meaning of “public” space and presenting a new model.

Otobong Nkanga, Taste of a Stone: Itiat Esa Ufok, 2013. Performance with gravel, rocks, epiphytes, and inkjet prints on limestone. Dimensions variable. Commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation. Installation view: Sharjah Biennial 11, Bait Khaled Bin Ibrahim Al Yousif. Image courtesy of the Sharjah Art Foundation.

Otobong Nkanga, Taste of a Stone: Itiat Esa Ufok, 2013. Performance with gravel, rocks, epiphytes, and inkjet prints on limestone. Dimensions variable. Commissioned by the Sharjah Art Foundation. Installation view: Sharjah Biennial 11, Bait Khaled Bin Ibrahim Al Yousif. Image courtesy of the Sharjah Art Foundation.

They included an “oasis” with three architectural projects as well as Superflex’s Bank, which turned a street that was temporarily closed for excavation into a park by assembling and arranging public furniture found in the home countries of these migrants, and inviting them to tell their own stories triggered by the memories and knowledge associated with this furniture. People thus became the actors who completed the work. In the evenings, people gathered and enjoyed themselves until midnight After the Biennial was over, public support enabled this installation to remain; recently, the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF) decided that it would be relocated and rebuilt. The people’s continuous use of the work made it a legacy.

My curatorial methodology consists of embracing such productive, positive criticality and imbuing it with a new life. For installations in gallery spaces, I create constellations by selecting and arranging the works in relation to specific locations so that each installation functions as a kernel of meaning, while paying attention to how relationships between the interior and exterior of these constellations, and the part and whole (biennial venues and the city), are constructed.

Collaborations with Artists

Artists have their own sharp powers of observation and the ability to interpret situations. Their creations spark an unexpected chemical reaction among the constituent elements of each place and at the scale of the decentralised biennial. In order to maximise a work’s impact in its given site, we must encourage both its ambition and its convergence with the biennial by providing the artist new information and brokering relationships, while also providing insight and advice that may give a sense of coherence and consolidation. Only a curator with a holistic grasp of the overall event can advise on how this tuning should be performed. For the participating artists, it is stimulating to be able to “visualise” each other’s perspectives as they take shape, and observe the varying progress of each other’s projects—a process akin to working in a vast laboratory or kitchen. Relationships with artists are very organic: each one is unique, just as ingredients dictate what kitchen utensils and cooking methods to use. When an artist becomes too self-absorbed they lose sight of the local context, which may lead to a serious deviation from a particular theme or disconnect from a place or environment.

The curator’s first task is to convey to the artist the relationship between the work and the place, that is, the context of reception or background for the work. It involves giving the artist a perspective on how the work will appear in that location. This does not entail pandering to local preferences; rather, it is a process in which the artists step into the realm of unknown, and perhaps unstated, norms and standards.

The other curatorial strategy is a capacious, umbrella-like theme. The themes of my biennials always combine a broad orientation, elements of abstraction, and unknowns that can be freely interpreted by each artist. Egofugal, Re-emerge/cultural cartography, Clouds⇄Forests: in each I strive to create a narrative imbued with a logic more akin to science fiction than fantasy. A curatorial narrative is a metatext: it presents the logic that defines the conditions under which the world is formed. Taking the structure of this world as a premise, each artist’s narrative should be spoken of in terms of a real, substantive structure or form.

I would never try to lead an artist toward a particular vision or a specific way of thinking. I work from the understanding that we are already connected with each other, flexibly performing actions that are possible within the scope of this relationship. As an Asian woman and a curator from Japan—a country that is not only rife with ambiguity but also ambivalent about its imperialist history and postcolonial position—I have always harboured both a longing for and a scepticism toward such notions as the subject, identity, and subjectivity. The discourse of the Other was always part of the discourse that shaped my own cosmology: my thinking centred on the creation of an organism that would allow the productive force of the other party (artist) to manifest itself and to proliferate. My intention is to bring artists into the exhibition space, a place structured by my own personal cosmology, to see how their individual organic attributes, systems of thought, and creative energies can come to life, exist, and reproduce themselves through the production of their work.

For this reason, my curation has often been called out for its lack of structural logic and critical politics. It has tended to be criticised for being post-historical, sensuous, and emotional. However, the essence of the biennials that I create lies in the space between things (or the environment in a New Materialist sense, which encompasses not just physical objects but also more intangible elements like information and data) and people, and between people and works of art.

The Biennial in the Post-Covid Era

During the pandemic, our gaze has been drawn introspectively towards our immediate surroundings and the domestic or feminine tasks that can be performed within the home. Many access the macro-reality through their own micro-environment and the global information with which they interact online. In this context, society and social spaces in the mid-range have become the hardest to access. Museums, music halls, exhibitions, and artistic activities exist at this middle distance. As the relationship between the emergence of the coronavirus and climate change becomes more obvious, there is a growing acknowledgement that this epidemic is not a transitory phenomenon. The biennial, organically dispersed in the city, has the potential to adapt its form to this new situation.

In the midst of Covid-19, both the global movement of goods and people and local production and consumption are being thoroughly reconsidered. The possibility of raising the “forest”—the body, the land, and history that are rooted in memory—up to the cloud (online) in a natural and fertile way is being explored, just as the evaporation of ground moisture becomes a (literal) cloud. While I am surprised that the ecosystem I proposed in Clouds⇄Forests three years ago has materialised in this way, I also recognise the likelihood that an exhibition or artwork may function as an oracle or as the canary in the coalmine.1 Contemporary art and curation are incubators of wisdom and methods of visualisation of change. In an emergency—a period of hesitation and confusion when we proceed by trial and error, unaware of what is to be done—art comes into its own, enfolding uncertainty and complexity in our intellect and sensibility, and inspires us to think. Let us reset the compass, as Bruno Latour called for us to do!2

What sort of technology will be able to compensate for the restriction of our movements? Much attention is currently focused on how information science is expanding knowledge of “humans” through the advances of AI. Though James Watson and Francis Crick may have shed light on the mysteries of life, the last frontier—consciousness and the workings of the brain—has only recently started to become the subject of science. Only three percent of our perception of the outside world is based on external information; the rest is produced by perceptual judgements based on data that our brain and gut already have. In light of this, we might also start to think about the kind of information design and data collection that would maximise our interactions with artists and staff when conducting research in the city, at the biennial site, and in studios. We can verify what can be shared about them by simulating the process of preparation, by having the data sent to us and printing their 3D representations. In addition, video communication, as well as the training and deployment of researchers as local agents and actors, will also be further refined.

The objective of the most advanced information science is now to develop technologies that exploit links between information, emotions, and sensibilities. We are seriously mistaken if we believe that our world is that different from the world as constructed and perceived by digital machines. For example, vibrations in a recording of glass windows can be used to recreate the conversation that took place in a room. To a machine, eyes and ears are identical. In the real world today, we merely look at screens; insofar as we do not have a physical sense of the digital world, our online access is extremely superficial. As the online environment becomes an important space of expression and communication, the task of the curator is not to shift to the digital, but to create a commons between the real and digital worlds. The biennial, which is capable of producing new spaces, is the perfect platform for tackling the challenge of creating this commons.

Phimai Historical Park in Korat, Thailand.

Phimai Historical Park in Korat, Thailand.

There is great potential for experiments being pursued in relation to the future of the biennial, and to embark on collaborations devoted to the creation of the commons. Conventional ideologies and anthropocentric philosophies have become dysfunctional; at the same time, science and materialism have been reconfigured and their functionality expanded. For instance, with its excursion into plant neurobiology, as proposed by Stefano Mancuso and others,3 biology now includes speculation and emotion as methods. And neo-materialism now encompasses spatial and information theory.

My challenge as director of the 2nd Thailand Biennale (2021) is to devise a system through which I can inductively capture all these shifting and muddled elements. The province of Korat, the gateway to the Isan region northeast of Bangkok, is no destination on the international map of cultural tourism. Its institutional and cultural assets include a zoo with a laboratory, veterinary hospitals, the Phimai ruins (believed to be the prototype for Angkor Wat), museums, universities, temples, parks, villages for sericulture and handloom weaving, and an ancient sanatorium. This project is inspired by the concept of “social common capital” advanced by the late Japanese mathematical economist Hirofumi Uzawa, who was once seen as a strong contender for a Nobel Prize. Social common capital is a third economic theory, which differs from both conventional capitalism and conventional socialism. It is premised on three forms of capital—the natural environment, social infrastructure, and institutional capital. Social common capital designates the production of educational and medical institutions, such as schools, hospitals, and museums, managed by experts: stable, rich, and abundant lives for all people.

Skateboard park in Korat, Thailand.

Skateboard park in Korat, Thailand.

Our curatorial narrative runs like this: we, the Biennale team and the artists, will help to create institutional and potential capital, and assist in the discovery and generation of resources. Cast as the experts, we are entrusted with these tasks. For example, Japanese designers will collaborate with local sericulturists to create fabrics with new patterns and make clothes from them, while Pnat, a think tank of designers and plant scientists, will set up an “air factory” using plants. Film and video artists will delve into the history of the Phimai monuments by linking them both to Angkor Wat and to the present. A team of university students and professors will help the artists in their production. They will act as co-producer, highlighting the potential of various sites including unused facilities, some of which will remain in use after the end of the 2nd Thailand Biennale, as a legacy. The Biennale team is a facilitator: it will work together with Korat, its people, and visitors, waiting to encounter something that will engender something else.

Pnat, Fabbrica dell’Aria, 2019.

Pnat, Fabbrica dell’Aria, 2019.

Because of international travel restrictions, we are currently deploying local staff as agents to gather information online and organise meetings with artists. In addition to on-site research in libraries and on exhibitions in Thailand, they are exploring what can be done under these circumstances. These are days of hesitation, groping, and confusion. Such collective wandering is the function of the biennial, today and in the future. After all, the elements of the “future” are already here: it is just that they are not all visible to us.

(Translated from the Japanese by Darryl Wee)

NOTES

- For instance, Egofugal (2001 Istanbul Biennial) heralded a shift from the three Ms (man, money, and materialism)to the three Cs (consciousness, collective intelligence, and coexistence). The 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center, which critiqued Western individualism and targeted global capitalism, had occurred just ten days before its opening. The 7th Moscow Biennale, Clouds⇄Forests, was inspired by the idea that tribal forest dwellers who produce art tied to traditions and memories of the body and the inhabitants of cloud spaces created by the internet would connect, working towards a circulatory ecosystem. Now, three years later, many forest artists have been forced to build online connections: this has also become a reality.

- Bruno Latour, Reset Modernity (Karlsruhe: ZKM, 2016).

- Stefano Mancuso, The Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and Behavior (New York: Atria Books, 2018).

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Yuko Hasegawa is Director of the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, and Professor at the Graduate School of Global Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. She has been an advisor, commissioner, and curator of numerous biennials including Thailand Biennale (2021), Moscow Biennale (2017), Sharjah Biennial (2013), Venice Architectural Biennale (2010), Bienal de São Paulo (2010), and Istanbul Biennial (2001). In addition, she recently curated Japanorama at Centre Pompidou Metz (2017-2018), and contributed texts to the edited volumes The Persistence of Taste: Art, Museums and Everyday Life After Bourdieu (New York: Routledge, 2018) and Modern Women: Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010).